A Naval Historical Foundation Publication, Spring 1979

ORIGINAL TEXT OF PAMPHLET

“Battle of Lake Erie: Building the Fleet in the Wilderness”

by

RADM Denys W.Knoll, USN (Ret.)

Acknowledgment

More pages in history are devoted to the story of the Battle of Lake Erie than to the building of the ships that fought that battle.

The Naval Historical Foundation is therefore grateful to Rear Admiral Denys W. Knoll, USN (Ret.), for permitting us to share with our members his account of the great difficulties involved in building Perry’s “Fleet in the Wilderness” and the great battle that fleet won.

The Admiral’s interest is understandable, for he was born in Erie, Pa. where Perry’s fleet was built. During his long naval career he served in numerous sea and shore assignments, including international assignments in his postgraduate school specialty, meterology. In addition, he commanded the Service Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, was Deputy Commander of the Military Sea Transportation Service, and served as Oceanographer of the Navy.

He retired in Erie, where he has been president of the Erie County Historical Society. He is also a long time member of the Naval Historical Foundation, as well as other historical societies in the United States.

Foreword

Why American posterity gives little more than scant appreciation to the historic importance of the War of 1812 is not understood. Perhaps this war came too close to the War of Independence; many men fought in both struggles.

It may be that all of the benefits won for us in the War of 1812 are popularly supposed to have been the fruits of our Revolution. History tells us otherwise. It took the War of 1812 to secure for us the full recognition and respect of world powers for our rights and priveleges as a soverign nation. The War of 1812 also firmly established our present northern border with Canada. It ended for all time British claims to certain territories in our country and the subsequent withdrawal of British troops from those territories.

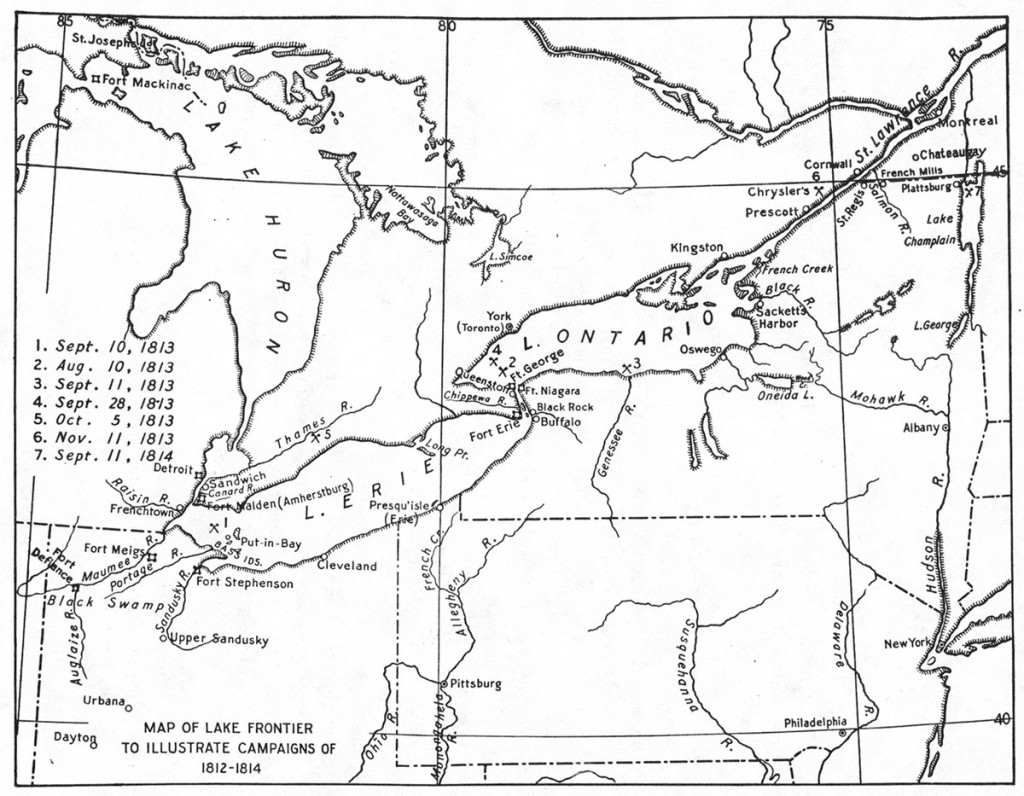

Crucial to winning the War of 1812, and with it the free exercise of our soverign rights, was the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. Unhappily, the Battle of Lake Erie, too, despite its enormous contribution to our heritage, shares the same unfilled recognition accorded the war in which it played so glorious a part. To the battle must also be added the almost hopeless challenge of building the Fleet in the Wilderness and the subsequent land actions in the Thames River area of western Ontario. Taken together, they constitute a triumph of the human spirit seldom equaled in man’s relentless struggles for freedom. These achievements will stand for so long as perseverance, patriotism, and valor are honored among men.

The purpose of this presentation is to set down in one place, and at one time, the full meaning of the enormous contribution these events have made to American heritage.

DWK

From “Seapower in Its Relation to the War of 1812 (Vol. 1, p. 371) by A.T. Mahan (Boston: Little, Brown, 1905).

Battle of Lake Erie: Building the Fleet in the Wilderness

Beginning in 1615 missionaries and explorers, principally French, paid visits to the Presque Isle (now Erie, Pa.) region of Lake Erie but no permanent white settlement was made until 1794 because of hostile Indians. In 1753 the French permanently established a transportation system of land and water routes from the St. Lawrence River to the Mississippi River. It went via Lake Ontario with land portage at the Niagara escarpment, thence across Lake Erie to Presque Isle (Erie), where another 14-mile land portage to Fort LeBoeuf (Waterford) connected with French Creek which flowed into the Allegheny at Franklin, thence onward to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and ultimately to the French settlement at New Orleans.

France and England hoped in the late Eighteenth Century to extend their colonial boundaries westward, but French control in North America was doomed with the British victory at Quebec in 1795 during the French and Indian War (Seven Years War). With the Peace Treaty of 1783 (ending the Revolutionary War), the British lost control of the south shore of Lake Erie. Indians, normally very loyal to the British, continued to harass white settlers.

A permanent white settlement at Erie was started in 1794 with the arrival of farmers from New England. Agriculture and lucrative salt trade were the initial business activity. Salt, originally from western New York State, was distributed by ship to the upper Lakes as far as Fort Mackinac (a white settlement since 1696) and by or cart to Waterford, thence by barge or raft to points south and west. This salt trade was so important in the area that salt was the medium of exchange.

From 1776 to 1812 Europe witnessed the rapid rise to power of Napoleon, and his increasing threats to the peace.

Since 1783 England has viewed the American Thirteen Colonies, and their newly-won independence, with suspicion; England harbored secret hopes for re-acquiring the United States as a part of her empire. The western wilderness was still ear-marked for future conquest and settlement.

In 1803 British plans were dealt the first of a series of disappointments when President Thomas Jefferson negotiated the Louisiana Purchase from France. Then in October 1805, with the defeat of the French and Spanish Fleets and Lord Nelson’s great victory at Trafalgar, England became undisputed mistress of the seas. With this new status the Royal Navy proceeded with impunity to impress our seamen, disregard our international neutral rights, and make unwarranted seizure of ships of the American merchant marine. On June 18, 1812, as a result of these wilful acts that inflamed large segments of the American public, the United States declared war against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. England did not seek nor desire a war with the United States then; her foreign trade had fallen off about one-third, and her public debt was huge.

It is worth nothing that when Benjamin Franklin received the news of the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown he remarked with foresight that the War of Revolution was won, but the War for Independence is yet to be fought.

In the United States the war was not popular, principally in New England, whose foreign trade has suffered badly from actions and policies of England and France. Congressional pressures from the west and south however, had urged a war, although the United States was ill-prepared for it. Washington officials placed their hope on quick Army victories, as the Nation was about to fight the then greatest naval power in the world.

War Comes to the Great Lakes

In July 1812 Captain Dan Dobbins in his ship Salina was delivering salt at Fort Mackinac in the northwestern part of Lake Huron when the fort was captured without warning by the British. (The U.S. officer in charge at the fort had not been notified that the U.S. was at war.) With the aid of influential friends Dobbins negotiated his release and proceeded to Detroit. Detroit fell to the British and Dobbis was again detained by the British. Again he was able to gain his freedom to proceed to Cleveland, and ultimately to his home in Erie. His arrival in Erie on August 24, 1812, brought the first news of the capture of Detroit and Fort Mackinac to the Erie area. There was great alarm that Erie would soon share a similar fate.

Dobbins reported conditions to General Meade who commanded the State Militia in northwest Pennsylvania. Meade agreed with Dobbins that the American shore of Lake Erie was defenseless, and requested Dobbins to proceed forthwith to Washington and make a full report to President Madison and his Cabinet. Dobbins promptly departed for Washington on August 25 or 26, 1812.

A short biographical sketch of Dan Dobbins illustrates his splendid qualifications for this mission. Dobbins was born January 5, 1776, in Wayne Township, Cumberland Country, Pennsylvania. He walked to Erie when he was 20, arriving via Colt Station on July 1, 1796. He quickly gained fame as best navigator and seaman on Lake Erie. He made regular trips on Lakes Erie and Huron carrying salt, whiskey, furs, and home and food products. Although he had no real shipbuilding experience, he had repaired, overhauled, and maintained the ships he operated including the Salina of which he was owner and master.

Capabilities of Erie Environs in 1812

Dobbins, at age 36, arrived in Washington on September 2 or 3, 1812. For the next ten days there were long and heated discussions with President Madison and his Cabinet concerning the defenseless nature of the American side of Lake Erie.

With the fall of Detroit the British had three small merchant ships converted to warships plus a small U.S. brig, Adam, captured with the fall of Detroit. The United States had no warships on Lake Erie, and essentially nothing with which to arm the few U.S. merchant ships. General William Henry Harrison (future President) commanded a few hundred U.S. militia encamped near Sandusky; however he was helpless. He could not initiate plans to re-take Detroit without naval support.

President Madison recognized the need for ships, and the necessity of building them on Lake Erie. (The Weiland Canal that today permits commerce to move between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario was not started until 1913.) The capabilities for building ships in the wilderness were reviewed in detail. Five settlements in the area had a variety of resources: Erie, Buffalo, Cleveland, Meadville, and Pittsburgh.

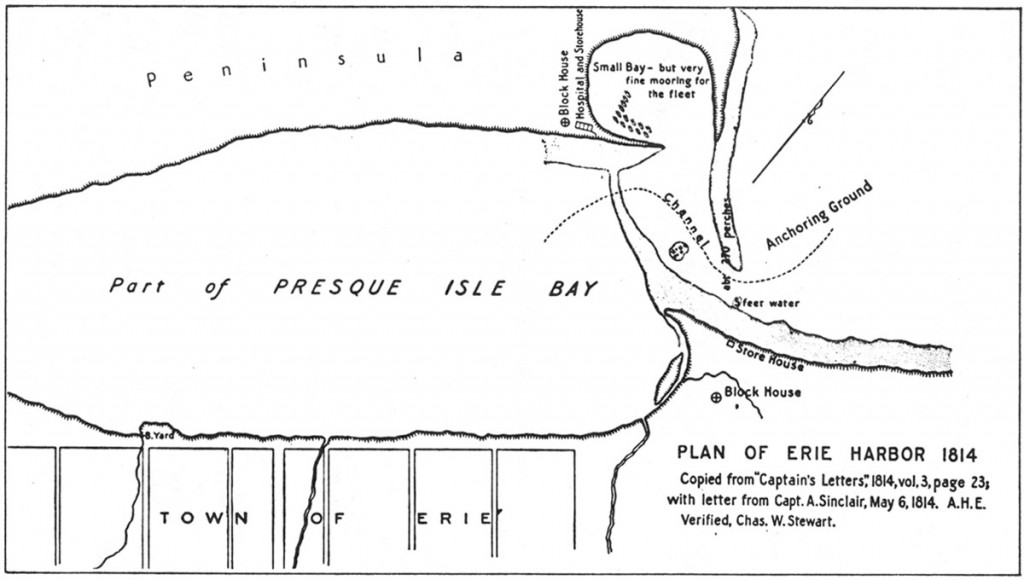

Erie was a hamlet of 400-500 people plus 200 floaters, and about 47 clapboard houses. Half of the dwellers on the U.S. side of Lake Erie lived in Erie. It had been a white settlement for only 17 years and had a grinding and saw mill, one blacksmith shop and a tannery. Settlers were farmers, merchants, sailors, and wagoners for the lucrative salt trade. Large oak trees and forests grew at the water’s edge, and Presque Isle peninsula completely enclosed a large bay. The bay was a safe harbor with an entrance channel protected by a sand-bar with a water depth of no more than six feet. Dobbins emphasized that ships could be constructed there and be safe from raids or attacks from the British. When completed, the ships could easily be sallied over the sand-bar into the deep water of the Lake. Dobbins was a skilled pilot and had no doubts that the ships could exit when built. Erie had an excellent safe harbor, and an unlimited supply of timber.

Buffalo, 100 miles east of Erie, had a population of 500 people, and about 100 frame houses and stores. Activites such as farming, trading, and sailoring were the same as Erie. Buffalo had little of value for work at Erie. Near Buffalo on the Niagara River was the Black Rock Naval Station, within gun range of British Fort Erie and Fort George.

Cleveland, 100 miles west of Erie, was a very new settlement just beginning to grow. Its growth had been less rapid than that of Erie or Buffalo. In 1812 the population was 47 people with no industry and no supplies.

Meadville, 50 miles south of Erie, had a population of 500 people composed of tame Indians, trappers, boatmen, and raftsmen. Meadville was a center for lucrative salt and lumber trade, and had a limited supply of metal and iron. It had thrived because it was situated near French Creek and the most advanced transportation system in the area, namely, the route pioneered by the French in 1753.

Pittsburgh, 130 miles south of Erie, had a population of 6,000 people. Pittsburgh grew rapidly after the Revolution, and became the “Gateway to the West”. It was larger than two cities in the area, and had foundries, cotton and fulling mills, rope walks, glass works, shops for many types of metal working, a few steam mills for grinding, grain; it was then entitled “Birmingham of America”.

Daniel Dobbins. Source: Papers of Dan Dobbins, Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society, Buffalo, New York.

Transportation and Communications in 1812

In 1812 there were no labor-saving devices, no power tools, no typewriters, no telephones, no radio, no telegraph, no regular mail service, and nothing that today we take for granted. The horse provided the most rapid means of travel. Letters were sent by courier, and each letter was written by hand, without Xerox or carbon copies.

The time to travel between Erie and Pittsburgh was three days one way; between Pittsburgh and Washington or Philadelphia was three days minimum one way. Philadelphia was the second largest city plus the cultural and industrial center of the United States. Mail and courier communications between Erie and Washington required one week minimum. Mail by courier from Pittsburgh to Erie and return was available once a week.

The most advanced travel route from Erie to Waterford via Old French Road, then by water to Pittsburgh. In summer when French Creek was too [rest of sentence missing].

From Pittsburgh travelers moved east on the Forbes military road through Lancaster to Philadelphia, or branched off through Hagerstown to Washington. Mail, merchandise, and travelers going west from New York City also usually used the Forbes military roads. The more advanced water route via Erie Canal from Albany to Buffalo was not started until 1817, and completed in 1825. Most other land routes were former Indian trails, generally very bad and dangerous with many swampy places and long delay when creeks were flooded and too deep to traverse.

Dobbins convinced President Madison and Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton that a fleet on Lake Erie was necesary, and that Erie was the only safe and suitable place on the Lake for construction. President Madison and Secretary Hamilton determined that Pittsburgh was an ideal base of supply for building ships at Erie, with an established means of communciations for the movement of supplies to Erie. The resources of Pittsburgh obviously influenced the decision to build ships, and build them in Erie. Skilled manpower was recognized as a great scarcity everywhere, and Pittsburgh was no exception.

On Septemnber 15, 1812, Dobbins received authorization from Secretary of the Navy Hamilton to build four gunboats at Presque Isle on Lake Erie, and was granted $2,000 with which to start the work. The next day, September 16, he was appointed a Sailing Master in the United States Navy.

About September 12, 1812, Captain Isaac Chauncey was ordered from New York City to Sacketts Harbor near the Thousand Island at the east end of Lake Ontario, to gain control of Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron, and others, if necessary. Chauncey was designated Commander Naval Forces on Upper Lakes. At Sacketts Harbor there were a few small, armed merchant ships based at York (now Toronto). Dobbins had been ordered to report to and keep Chauncey advised of progress in Erie. On September 26, 1812, Dobbins was back in Erie, and arranged for men to make more axes, and to begin felling trees suitable for ship construction.

Building Wooden Ships

From “Seapower in Its Relation to the War of 1812 (Vol. 2, p. 73) by A.T. Mahan (Boston: Little, Brown, 1905)

The purpose of warship design is now and has always been to procure some advantage over the known qualities of the ships of one’s enemy or potential enemy. A large number of naval actions of the American Revolution were fought and won with privateers. These privateers were merchant ships that had been armed for naval warfare. But as guns became heavier, ships were specially designed for war, making them unsuitable for commerce.

In 1800 the British Navy classified ships in six Rates, depending upon the number of guns and the manpower required to man all guns. The First Rate was a three-decker with 100 guns, length 178 feet on the gun-deck, and displaced approximately 2,000 tons. The length of a wooden ship was limited by and dependent upon the size and strength of the wood available for the keel.

The sixth Rate was a gun-brig, length 113 feet, beam 30 feet 6 inches, crew 130 or 140, armament 16 32-pounder carronades, and two 6-pounder long guns. Sixth Rate ships were frequently used by the British and American navies during the Revolutionary War.

All ships were completely dependent on the wind for movement. Long oars (sweeps) were generally available for small movements while anchoring or getting underway.

An important 18th century innovation in naval gunnery was the carronade, a type of gun invented by General Robert Melville, and made for the Royal Navy by the Scots firm of Carons. (For more information on carronades, see Spencer C. Tucker, “The Carronade,” Naval Institute Proceedings, August 1973, pp. 65-70.ED.)

The carronade was basically a short, light-barrelled gun with a large bore. It threw a heavy ball from 32 to 68 pounds, with a low initial velocity. At short range (one half mile) it had a crushing effect more destructive than the swift passage of a ball from guns designed for longer ranges (two miles) which threw shot at higher velocites. The outer end of the gun carriage was attached with one vertical bolt to the base of the gunport. One great advantage of the carronade was that it made traverse firing possible.

An active battery of carronades could be disastrous to a carronade-armed ship if a superior enemy sailing ship with long guns stood off out of range of the carronades and battered the carronade ship until it surrendered.

Ebenezer Crosby, a master shipwright, was hired by Dobbins to start work on the four wooden ships. Crosby was carried on the roster from November 1812 until June 1813, after which no further information about him is available. Crosby was singularly responsible for excellent initial laying down of the ships .

Dobbins, as project manager, was busy on many things. Upon return to Erie, Dobbins promptly wrote Captain Chauncey as he had been directed by the Secretary of the Navy. In addition, he went to Black Rock naval station to make an appropriate report and obtain guidance. On this meeting the only person that Dobbins met was a Lieutenant Angus.

About the time Chauncey was ordered to Sacketts Harbor, Master Commandant Jesse D. Elliott was ordered to Black Rock (near Buffalo) to be in command of Naval Forces on Lake Erie (next in seniority to Chauncey).

Dobbins failed to receive a reply from Captain Chauncey; however, shortly after the visit with Lieutenant Angus, Dobbins received a letter from Elliott which in essence ignored the authorization from the Secretary of Navy to Dobbins and stated, in part, “It appears to me utterly impossible to build gunboats at Presque Isle …. You shall again hear from me.”

Elliott began the conversion of five small merchant ships at Black Rock as a naval squadron for Lake Erie operations.

Dobbins quickly replied to Elliott’s letter saying, “I believe I have as perfect a knowledge of this lake as any other man on it, and I believe this is the place [Erie] for a naval station.”

Dobbins continued work on the ships, assisted by Crosby. Dobbins’ purpose was clear, as directed by the Secretary of the Navy: To build four ships to defeat and drive from the waters of Lake Erie the British fleet under Commodore Barclay, and to regain dominion and control of Lake Erie for the United States.

Dobbins neither hesitated nor faltered. The mouth of Lee’s Run (between Peach and Sassafras Streets in Erie) was selected as the site on which to build ships. Lee’s Run disappeared from local maps when the Erie Extension Canal used the creek-bed of Lee’s Run as the route for the Erie Extension Canal connecting Erie with Pittsburgh in 1844.

Cascade Run, which flowed into the bay at the foot of Cascade Street, was selected as the site for a second shipyard.

Dobbins was busy with local labor problems, lack of trained craftsmen, accommodation for workers, finding scarce material, especially iron for nails and the making of adzes, axes, and chippers. Food was rationed, prices of food, meals, and accommodations were frozen, and drastic measures were taken to stop profiteering.

Every detail of the ships had to be wrought by hand. There was not a gallon of paint, or oil, or a single pound of iron or copper within a hundred miles. Guns, sails, rope, cannon, cannon balls, and powder would have to be moved over former Indian trails to Erie.

By December 12, 1812, Dobbins had not received a single word from Captain Chauncey, and no further word from Elliott. In desperation he sent a letter to the Secretary of Navy reporting no word had been received from Chauncey, and that he visited Black Rock to obtain instructions, but without success. Dobbins told the Secretary he was “at a loss what to do,” and that his friends had persuaded him to go on with the order to build four gunboats, 50 feet in length, 17 feet beam, and draft 5 feet. He requested more money to meet new obligations, reported the local people as very poor, the roads very bad, and ended his report with a plea that the Secretary direct him to go on with the work he had started. This letter, direct to the Secretary of the Navy, undoubtedly annoyed Chauncey and Elliott but it produced results.

On New Year’s Eve 1812, without warning, Captain Chauncey, accompanied by Henry Eckford, a ship designer and builder who later achieved national renown, arrived in Erie. Captain Chauncey visited for one day and departed New Year’s Day, 1813, never to return. Chauncey’s visit resulted in:

(a) many alterations in the work Dobbins had started;

(b) two ships being considered too small to cruise safely on Lake Erie, and their length was increased 10 feet;

(c) authorization to build two additional brigs (the Lawrence and Niagara);

(d) the Secretary of the Navy, on January 27, 1813, contracting for 37 32-pounder carronades to arm the Lawrence and Niagara;

(e) Noah Brown, a master shipwright from New York City, being ordered to Erie to supervise construction (in February 1813 he traveled from New York to Erie in record time – 10 days;)

(f) Captain Chauncey, in February 1813, requesting the Secretary of the Navy to order Oliver H. Perry to Erie to command the Erie squadron.

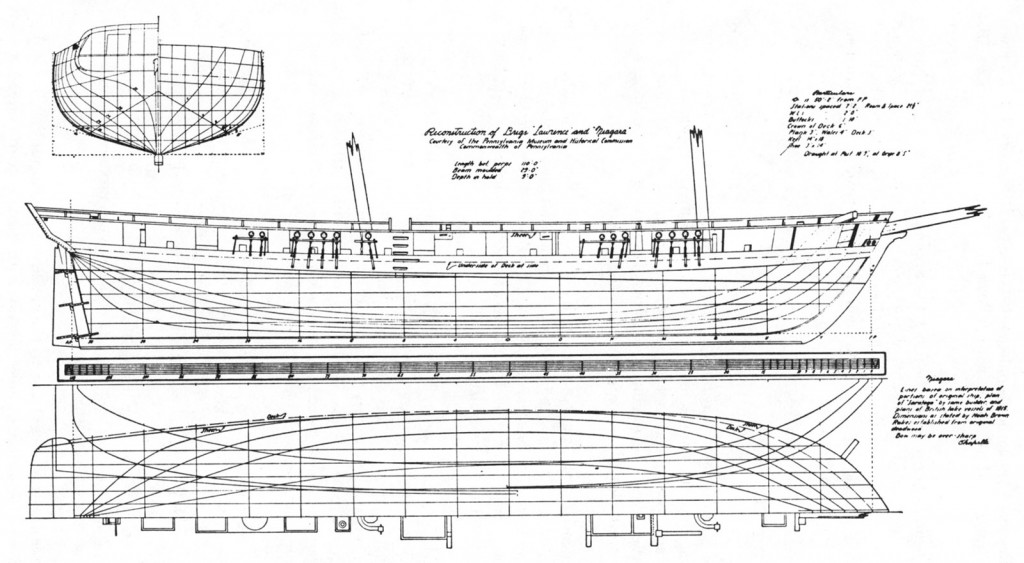

Lawrence and Niagara: Gun-brigs

The gun-brigs Niagara and Lawrence were constructed at Cascade shipyard. They were sister ships and were built exactly alike:

- Length, 118 feet; Beam, 30 feet; Draft loaded, 9 feet;

- Keel, black oak timber 14 inches x 18 inches.

- Frames, 12 inches wide at keel; Center distance of frames, 21-11/2 inches.

- Planking, three inches thick of oak;

- Length of gun deck, 100 feet;

- Armament, 18 32-pounder carronades plus two long 12-pounder guns (chasers well forward in bow);

- Square rigged two-masted ships with top-gallants on both;

- Bulwarks, white pine; Stanchions, red cedar and black walnut;

- Gunports, 36 inches square (10 foot centers).

Trees were selected for the frames so that knees and bends provided smooth lines from stem to stern. Each frame was from a single tree, extending keel to main deck. This construction gave the brigs great strength, and ability to bear shocks and strains.

Due to a lack of iron for hand-wrought nails, a large part of the hull was held together by wooden pins – “tree nails” (trunnels in sea lore). There was a complete lack of oakum and pitch for caulking all seams and making the ships water-tight, so lead caulking was used with great success. The green timber should have been seasoned for about one year. (When the Niagara was raised in 113 the lead caulking was still firmly in place.) Lead caulking of the green timber undoubtedly produced a water-tight hull superior to oakum and pitch.

Trees were paid for at the rate of $1.00 each to the owner of the land where cut. Records of each payment were recorded by Dobbins. One dollar in 1813 was considered the day’s wage for a skilled worker.

Let no one think that the ships built at Erie were make-shifts, crudely framed, and knocked together by woodsmen on the shores of Lake Erie. The highest skill entered into their design and construction, and the citizens of the hamlet of Erie, led by Dan Dobbins, have never received due credit for their heroic work of building six wooden ships of green timber in eight months.

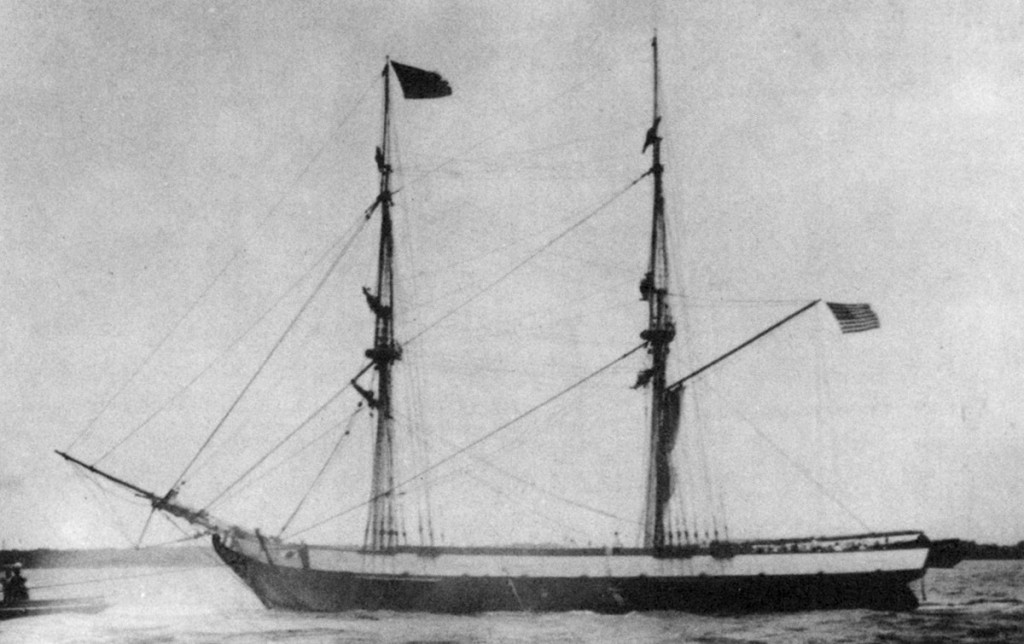

Reconstructed brig Niagara, c. 1923. The original Niagara was raised in 1913 and reconstructed for Perry Victory Centennial. The ship is now preserved ashore in Erie, PA.

Oliver Hazard Perry

In February 1813 Perry received orders to proceed to Erie. Oliver Hazard Perry (28 years old at the time of the battle) was born August 23, 1785, at Westerly, Rhode Island. His Quaker ancestors left England in 1600, and his father was a captain in the Navy during the Revolution. Perry went to sea as a youngster, and had many relatives and close acquaintances among senior officers of the U.S. Navy. He was skilled seaman, a dignified, calm, selfpossessed officer who was admitted by officers and crew. He possessed an uncanny ability to pick the right man for the right job. He was firm in his discipline, insisting everyone do his work without friction. There is frequent reference to “Perry’s Luck”; he had rare abilities and an orderly mind. Again and again in his career the unexpected happended at exactly the right moment .

On February 22, 1813, Perry was promoted to commodore and left Newport, Rhode Island, with 150 of his best men and his younger brother, Alexander. His orders were to go direct to Erie; however after nine days of winter travel he arrived at Sacketts Harbor and reported to Captain Chauncey. Chauncey retained the men, and detained Perry for two weeks to assist if a British attack on Sacketts Harbor materialized. On March 26, 1813, Perry arrived in Erie after long and arduous winter travel, requiring 11 days from Sacketts Harbor.

Upon arrival Dobbins fully briefed Perry, emphasizing the defenseless condition of the ships and the town. Perry recognized the danger, sent for General Meade, and held a short conference. A thousand militia were in camp on Garrison Hill. These militia were gradually reinforced by several hundred volunteers.

The majority of citizens on the Canadian shore of Lake Erie were British sympathizers who had moved to Canada at the end of the Revolutionary War. They were excellent spies for the British, who had better information concerning Perry’s movements and the progress of construction than Perry was able to obtain concerning the British.

Block-houses were built and manned near each shipyard and to guard the harbor entrance. There was real concern that a prowling spy, or enemy agent, or incendiary in an unguarded moment would destroy all.

After four days of briefing’s Perry, realizing Dobbins had local problems under control, on March 31, 1813, went to Pittsburgh on the first of many trips to contract for supplies and to locate carpenters and workmen who had been sent from the East coast to work in Erie. Some 200 carpenters and shipbuilders, who were sent in March, did not arrive in Erie until May; some never arrived. At one point the Secretary of the Navy issued orders to send workers in wagons as fast as possible, saying “select foreman to guide them to Erie, such foreman should be a steady, clever man whom the men will obey cheerfully.”

Contracts were made in Pittsburgh for iron, canvas, cordage, rigging, anchors, cannon balls, and other equipment.

Shipping the cannon to Erie was a hazardous undertaking; in all 65 cannons were sent – 37 from Washington and the remainder from Sacketts Harbor. Fourteen wagons with four men each carried the carronades from Washington to Pittsburgh, requiring more than one month for the trip. The carronades were made at the foundry of George Foxall in Georgetown. Foxall promised that, if Perry won, the foundry owner would build a church. Visitors to Washington, D.C., can see the Foundry United Methodist Church on 16th Street as visible proof of Perry’s victory.

Approximately 150 ship carpenters eventually reached Erie from New York City. In addition, block-makers, sail-makers, and riggers came from Philadelphia.

The only large building available was the Court House at the southwest corner of Central (now Perry) Square. It was used to cut, sew, and assemble the sails.

The Niagara and Lawrence had the graceful lines of a small clipper ship, with top-side cumbered with bulwarks and gun-ports; Henry Eckford was the naval architect.

Ballast for the ships should have been pig-iron, but none was available so the Secretary of the Navy wanted Perry to use stone ballast. The shallow draft ships had insufficient space for the required amount of stone ballast so Perry ordered lead to be used because it was readily available, and because if at any time lead became necessary to resell, nothing would be lost in transaction.

There was never a lack of axemen, chippers, and sawyers. Wagoners with horse or oxen were also abundant.

By April of 1813 Perry’s “Fleet in the Wilderness” had begun to take shape. Tigress and Procupine were launched in April from the yard at Lee’s Run, followed in early May by Scorpion from the same yard. The brig Lawrence was launched June 25 at the Cascade Yard, followed by Niagara and pilot boat Ariel on July 4.

With neutralization of the British Forts Erie and George on the Niagara River, five converted merchant ships–Somers, Trippe, Ohio, Caledonia, Amelia–were moved from Black Rock to Erie without being detected by British units patrolling Lake Erie. Upon arrival in Erie, Amelia was declared unseaworthy and not used.

A reconstruction of the brig Lawrence and Niagara. Source: Howard I. Chapelle, The History of the American Sailing Navy, New York: W.W. Norton, 1949) p. 271 (by permission W.W. Norton)

Crossing the Bar

The Lawrence and Niagara were the largest ships, with drafts of 9 feet. Today these ships are considered small, but in 1813 they were immense. They were a great curiosity and looked formidable compared with anything seen before on the Lakes. The big guns were giants of destruction to the citizens, and Erie felt a security it had not experienced for the past year.

On August 2, 1813, the Lawrence with Dobbins as pilot was kedged to the entrance channel. Dobbins had especially sounded and buoyed the best route over the sand-bar. The Niagara was moored nearby ready to defend while the Lawrence was stripped of guns, ballast, and all heavy material. A field battery on Garrison Hill was also on alert.

“Camels,” designed and built by Noah and his brother Adam Brown, were placed alongside the Lawrence. The camels were oblong barges with square ends, 90 feet in length, 40 feet wide, and six feet depth of hold, with a strong deck. Two holes were cut through the bottom, six inches square, with guides for long plugs to close holes when required. Timbers athwart decks and through gun ports were placed in preparation for lifting the Lawrence about three feet.

Camels were flooded, and timbers securely lashed. The holes in the camels were plugged up, and the water slowly pumped from them. As the water was discharged from the camels, the ships was slowly lifted. The Lake level was lower than normal, and the operation had to be repeated. After a laborious night and day, the Lawrence was floated safely over the sandbar and towed to an anchorage by the early morning of August 4th. By 2 P.M. the same day, under Perry’s leadership, everything was replaced, guns mounted, a salute fired, and the Lawrence was ready for action.

The Niagara was next towed to the entrance channel, as the British fleet hove into view about seven miles distant. The British reconnoitered for an hour or more, failed to observe the precarious nature of Perry’s fleet, and stood across the Lake toward Long Point. Dobbins explained to Perry that hazy weather, the sun to the south, the 40 to 50 feet of bluff, with forests to the shoreline, all served to mask the masts of the fleet and prevent the British from seeing the maneuvers in the channel. The pilot ship Ariel followed the enemy ship until it was safe to return and signal it was safe to move the Niagara.

Lightening the Niagara went rapidly. In a few hours everything was on the beach, the camels were in place, and by August 5th (less than 24 hours) the Niagara was over the bar and fully equipped for battle. All hands had learned their lessons well with the movement of the Lawrence.

Without delay Perry ordered all ten ships underway for a quick shakedown cruise on the Lake beginning at noon August 6th.

At this time the Pittsburgh Gazette published an extra special edition describing the movement of ships into the Lake, and announcing the new defense on the Lake frontier.

The fleet, which a mere nine months before had been trees in the forest or supplies in distant places, was afloat on Lake Erie ready to vie with the British for its control.

Lake Erie on August 6th was unknown to Perry. His crews were green, many having never been on a ship before, and most knew nothing about navigating a ship. He also lacked capable officers to command the ships. So he took advantage of the earliest opportunity to test his ships and give his green crews a little sailing experience.

Perry had written a series of letters to Captain Chauncey pleading for the men that had been promised him to man the ships. In desperation, like Dobbins in December of 1812, Perry wrote the Secretary of the Navy direct.

A recruiting station had been opened in Erie. Landsmen were offered a chance to serve as militia and promised ten dollars a month, with a share in any prize money. Terms of enlistment were four months, or until a decisive battle had been fought. A maximum of 40 volunteered.

For the first cruise there were barely 300 officers and men with which to man the two brigs (each requiring 130 men) and the other eight ships. Manpower was needed but Perry decided to wait no longer, and made plans to proceed to the vicinity of Put-in-Bay. The fleet returned to Erie on August 7th to prepare for the longer cruise to Put-in-Bay. Provisions, shot, and powder were loaded. Storage space was limited.

The next day, August 8th, word arrived that Elliott was enroute from Black Rock with 89 men, some of whom had started from Rhode Island with Perry. Going over the head of Chauncey again had been productive. Perry delayed this departure for three days while he sent Ariel to the vicinity of Silver Creek to pick up and expedite movement of Elliott and his men to Erie. Upon his arrival on August 10th Elliott was promoted to commodore to rank after Perry, and was given command of the Niagara with more than ample crew.

Elliott had been senior to Perry on the active rolls of the Navy, but Perry superceded Elliott when he (Perry) assumed command of the Lake Erie forces that Elliott had hoped to command. Elliott’s actions during the battle of Lake Erie may have been caused by hard feelings about promotion and the two instances when Dobbins and Perry had each appealed directly to the Secretary of the Navy, ignoring the chain of command.

Perry departed for Put-in-Bay area and conferences with General Harrison near Sandusky. General Harrison provided him 100 expert Kentucky and frontier riflemen to serve in the ships as marines.

British Situation at Fort Malden

Commodore Robert H. Barclay, commander of the British flotilla based at Fort Malden, was a distinguised British officer with a fine record. He had been at sea most of his life, starting as a boy of 10. Barclay had been with Lord Nelson at Trafalgar, where he was seriously wounded. Later, in another naval engagement with the French, he had lost an arm. He never wanted to command the British squadron on Lake Erie, but as a good sailor, he obeyed when ordered and did his best.

Barclay, like Perry, was very short of experienced personnel. Four of his ships were quite small, having been hastily converted from merchant ships to war purposes. At no time did Barclay have more than 50 men who had ever served at sea. His crews were soldiers serving as marines, Canadians, and a few Indians. His requests for more personnel had produced no results. The strongest and best ship was his new flagship, Detroit. The Detroit was undoubtedly built as a match for the Lawrence and Niagara, after British spies reported such construction at Erie. Construction of Detroit had to be completed before Barclay was ready for action.

Detroit, like Lawrence and Niagara, was constructed of green timber. She was probably better reinforced for war because her frames were closer together, almost touching; her bulwarks were thicker, too, providing better proof against grape shot than her opponents’. But adequate naval guns had not been ordered for the Detroit, thus forcing her to use the only guns available: 19 land guns from Fort Malden. No warship ever had a more unsuitable battery.

Fort Malden, where Detroit was built, had a population of about 14,000 people (Indians, Canadians, and civilians) who depended completely on the army commissary for food. British control of Lake Erie permitted a regular resupply of food and provisions from Long Point.

While the Detroit was under construction at Fort Malden, Perry had almost a month in which to train his crews and prepare for action. He frequently cruised within easy view of Fort Malden during this month, essentially blockading it and causing all the supplies there to get dangerously low. An uprising of Indians and the local populace was feared if food was not available, thus creating a situation that forced Barclay to sail forth to meet Perry’s fleet as soon as Detroit had been completed.

Because Perry’s intelligence on the British was spotty, he did not realize the real conditions at Fort Malden. He had, however, acquired fairly accurate information about the armament and tonnages of the six British ships.

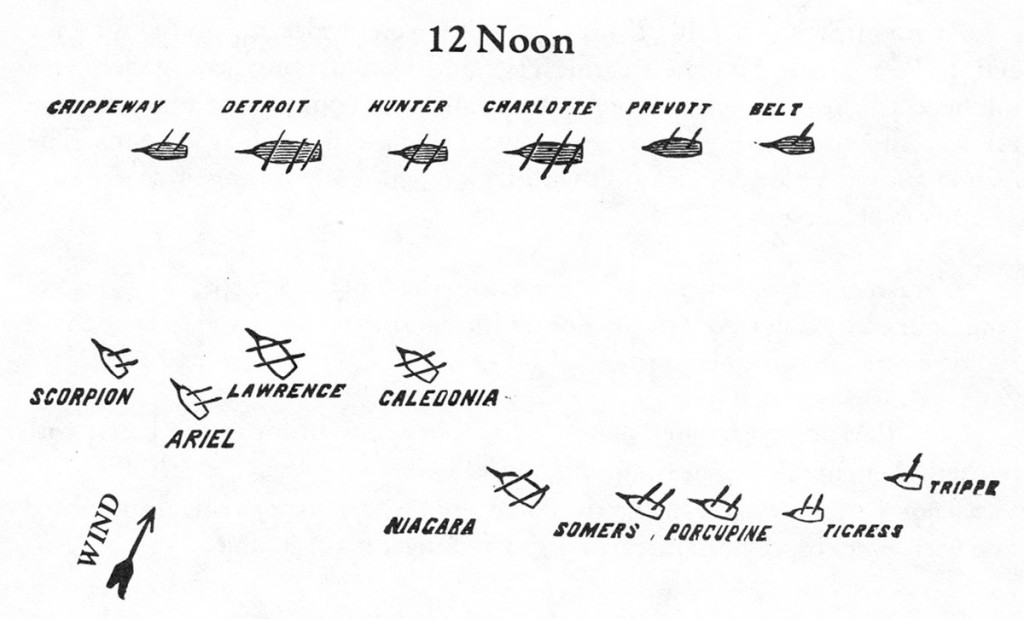

The tonnage and armament of the two fleets is shown in the table below:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tonnages of the fleets were about equal, Perry’s having 14 tons more; the British had 63 guns, nine more than Perry’s 54 guns. The Detroit was a three-masted gun-brig with 19 long guns, at long range more than a match for any three American ships. The Queen Charlotte was smaller than the Niagara with 17 guns, 14 of which were carronades; the Lady Prevost was a large schooner with 13 guns.

The Hunter was a small brig with 10 guns, two of which were carronades.

The Chippeway was a schooner with one long gun, and Little Belt was a sloop with three guns, two of which were carronades.

One gun – Underway to get.

Green at the fore – Form the order of sailing ahead.

Green at the main – Form the order of sailing abreast.

Green at the main peak – Form the order of battle on the starboard tack.

Green in the fore rigging – Form the order of battle on the larboard tack.

Green in the main rigging – Close more the present order.

White at the main – Tack.

White at the main peak – Follow the motions of flagship.

Ensign at the main gaff – Engage the enemy.

White at the main, with stop in the middle – Chase.

Ensign in the fore rigging – Repair on board flagships, all Commanders.

Green and white at the main gaff – Come within hail.

It is expected Commanders will pay strict attention to the orders of sailing.

No property other than public, or passengers to be received on board any of the vessels under my command.

“O. H. PERRY.”

Perry, with his squadron, was anchored near West Sister Island ready to get underway as soon as the British ships began to sortie from Fort Malden. All officers had been fully instructed, given a written Code of Signals, and each ship was assigned a British to take under fire.

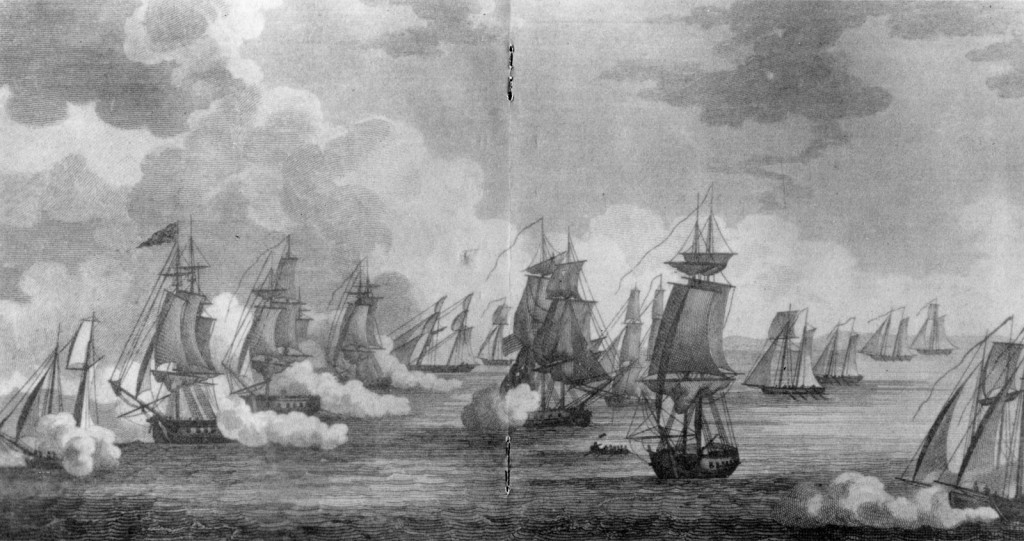

British and American squadrons at the beginning of the Battle of Lake Erie. Source: Theodore Roosevelt, The Naval War of 1812, 6th ed. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897)

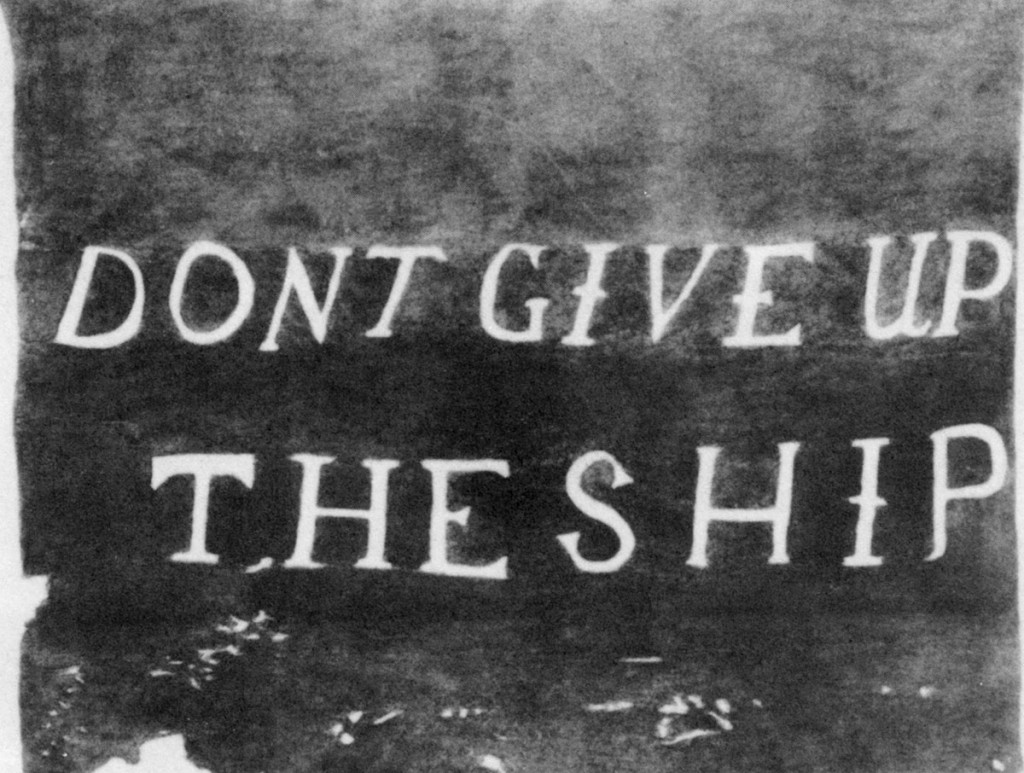

Before leaving Erie, Perry had a blue flag, with the words “Don’t give up the ship” in white, made for hoisting at start of action. These were the dying words of Perry’s close friend, Captain James Lawrence, who three months before was mortally wounded in the engagement between Chesapeake and Shannon near Boston.

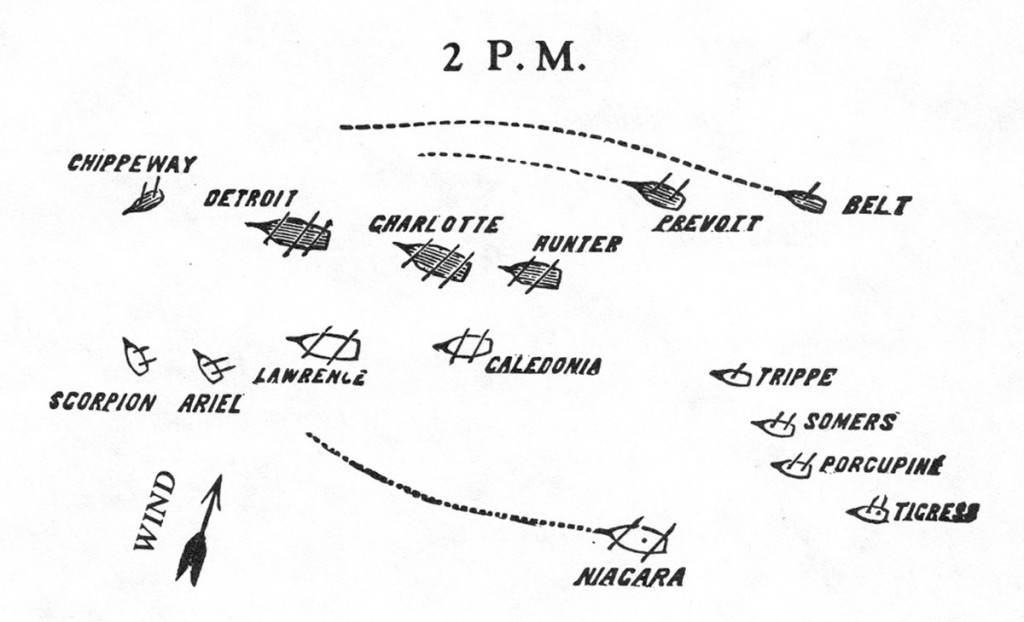

At noon September 10, 1813, both fleets were underway and closing for action. Perry’s fleet had the weather gage and maneuvering advantage. Perry intended to close the British quickly to a range of about one-half mile to take full advantage of the carronades, and avoid damage from the long guns. The Detroit started action about noon with its long guns when range was about 1-1/2 miles. The first shot fell short.

All American ships moved to engage the enemy except the Niagara, commanded by Elliott, did not maintain formation and appeared to lag behind taking a small part in the action.

By 2 P.M. Perry, in the Lawrence had borne the brunt of the battle with withering enemy fire from the Detroit and Queen Charlotte. By 2:30 P.M. the Lawrence, with every gun in the ship’s battery on the enemy’s side dismounted and with every brace-line shot away, was no longer manageable.

Perry noted the Niagara was intact, called for a small boat with four oarsmen, and transferred to the Niagara, accompanied by his brother Alexander. The British, seeing the above movement, thought the Lawrence was about to surrender, ceased firing at the Lawrence, and assumed the British had won the battle.

Casualties

AMERICANS

| Vessels | Tons | Guns | Crew | Killed | Wounded | Commanders | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence | 1 | 480 | 20 | 136 | 22 | 61 | O.H. Perry – Lt. Turner | |

| Niagara | 2 | 480 | 20 | 155 | 2 | 25 | Capt. Jesse D. Elliott | |

| Caledonia | 3 | 180 | 4 | 53 | — | 3 | Purser H. Magrath | |

| Somers | 4 | 94 | 2 | 30 | — | 2 | Master Thos. C. Almy | |

| Ariel | 5 | 112 | 3 | 36 | 1 | 3 | Lt. John Packett | |

| Scorpion | 6 | 86 | 2 | 35 | 2 | — | Msr. Stephen Champlis | |

| Tigreas | 7 | 96 | 1 | 27 | — | — | Lt. A. H. M. Conkling | |

| Porcupine | 8 | 83 | 1 | 25 | — | — | Midsip. George Sensi | |

| Trippe | 9 | 60 | 1 | 35 | — | 2 | Lt. Jos. E Smith | |

| Totals | 9 | 1671 | 54 | 532 | 27 | 96 |

BRITISH

| Vessels | Tons | Guns | Crew | Killed | Wounded | Commanders | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit | 1 | 490 | 19 | 160 | — | — | Capt. R. H. Barclay | |

| Queen Charlotte | 2 | 400 | 17 | 135 | — | — | Capt. Finnis | |

| Lady Provost | 3 | 230 | 13 | 91 | — | — | Lt. Com’d’r Buchas | |

| Brig Hunter | 4 | 180 | 10 | 49 | — | — | Lt. Bignall | |

| Sch. Chipppewa | 5 | 70 | 1 | 27 | — | — | Master Campbell | |

| Little Belt | 6 | 90 | 3 | 40 | — | — | ||

| Totals | 6 | 1460 | 63 | 502 | *41 | *94 |

* As reported by Captain Barclay.

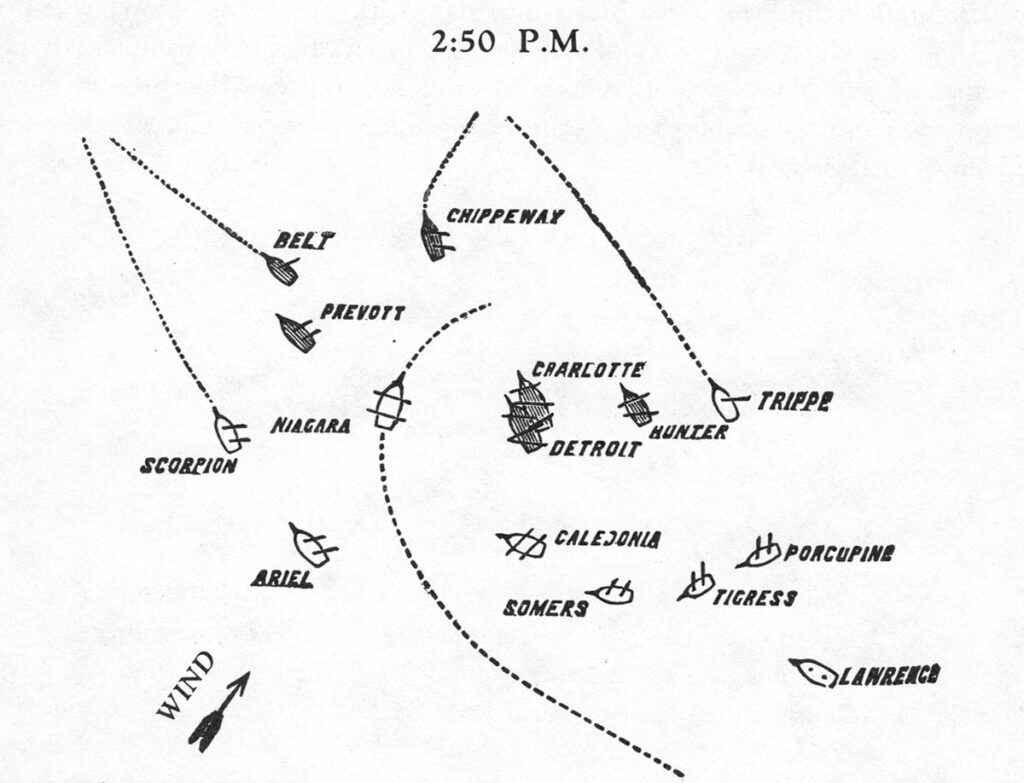

Fifteen to eighteen minutes after Perry boarded, about 2:50 P.M., Elliott had been sent in a small boat to reform the smaller ships. Perry quickly maneuvered the Niagara to cut the enemy line of formation with the Lady Prevost and Chippewa on his porthand and the Detroit that had collided with the Queen Charlotte on his starboard hand. Perry ordered both broadsides loaded, raking the Lady Prevost at half-pistol range, and firing a full starboard broadside at the Detroit and Queen Charlotte.

By 2:50 P.M. the battle ended and Perry was ready to send his famous message to General Harrison: “We have met the enemy and they are ours – two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop.”

Casualties on both sides were heavy. In Lawrence, 83 of her crew of 103 were either killed or wounded (although Perry and his brother came through unscratched). Twenty-seven Americans were killed (22 in Lawrence, and 96 were wounded (61 in Lawrence).

British casualties were even heavier, with a total of 135 killed or wounded. Barclay was wounded and unable to participate at the end; Captain Finnis of the Queen Charlotte was killed early in the battle, and his second officer severly wounded. Lady Prevost left her wounded on deck as her crew fled below.

At this point it is inspiring to read and ponder over the brief letter Perry quickly wrote and dispatched to Secretary of the Navy William Jones:

“U.S. Brig Niagara off the West

Sister Is., Head of Lake Erie, Sept. 10, 1813

4 P.M.

Sir:

It has pleased the Almighty to give to the arms of the United States a signal victory over their enemies on this Lake – the British squadron consisting of two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop have this moment surrended to the force under my command, after a sharp conflict.

I have the honor to be

Sir

Very respectfully

Your obedient servant

O.H. Perry”

On September 10, 1813, Perry and less than 1,000 combatants set the course for the future peaceful development and greatness of the United States. One month later, October 19, 1813, 500,000 combatants at the Battle of Leipzig gave Napoleon his big military defeat, leading to his eventual exile and removal from power.

Perry’s famous battle flag, with James Lawrence’s inspiring words, occupies a place of prominence today at the U.S. Naval Academy. It was made in Erie by a group of ladies led by Mrs. Margaret Foster Stewart.

In Britain Perry’s victory was received with alarm. The Duke of Wellington was summoned and requested to proceed to Canada with necessary troops to recapture western Canada and control of the Lakes. Wellington refused, stating that without naval control of Lake Erie and the upper Lakes a successful land operation was impossible. Two years later the same Duke of Wellington was the victorious general in command at the Battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815).

Perry’s victory was the turning point in the War of 1812. It was the first victory that mobilized and electrified the nation, and other victories followed. Perry’s victory pointed the way and the war came to an end on Christmas Eve, December 12, 1814, with the Treaty of Ghent.

Unfortunately, Dobbins did not take part in the actual battle. He commanded the Ohio and made at least two trips between Erie and Put-in-Bay supplying Perry’s squadron with food and provisions. The hot weather of summer with no refrigeration caused food, especially meat, to spoil quickly. A large percentage of the crew were always sick with “fever,” believed to have been due to bad food.

After the battle Dobbins did receive a Sailing Master’s share of the prize money. However, for unknown reasons Dobbins failed to receive one of the swords presented by Congress to all commissioned officers who participated in the battle.

During the War of 1812 the U.S. government spent about $2,500,000 for the ships on Lakes Erie and Ontario. Only a small part of this money went into the building of the Lake Erie fleet. In no way was the cost of building excessive.

Perry destroyed British seapower west of the Niagara escarpment; he quickly assisted General Harrison with fleet units at the Battle of Thames, which brought all western upper Canada (Ontario today) under American control.

The United States thrilled to Perry’s victory at age 28; six years later on his 34th birthday (August 23, 1819) he died at sea of yellow fever near Trinidad while on a special diplomatic mission for his country to Venezuela.

Remembering Franklin’s prophetic observation when Cornwallis surrendered, the War of 1812 was indeed our war for independence, and in reality the final decisive finale to the Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Lake Erie decisively determined the present northern boundary of Lake Erie, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, and westward, rather than the British intent of the Ohio River westward to the Mississippi River. The long geopolitical scheme of the British empire for North America was destroyed forever.

Within four years, in 1817, President Monroe was inaugurated and enunciated the Monroe Doctrine, permitting the United States for more than 100 years to seek its destiny and present greatness.

This then is the account of the Niagara and the ships she led, the incredible hardships and handicaps, natural and manmade, under which the fleet was built, and how she helped so indispensably to shape the first defeat of a British fleet at American hands in the War of 1812.

Epilogue

After her decisive role in the Battle of Lake Erie, Niagara covered the landings at the mouth of the Detroit River in late September, then covered the Army’s advance up the Detroit to Lake St. Clair in pursuit of the retreating British. The following spring she return to patrol and convoy duty, and captured the British ships Mink, Nancy, Perservenance and Batteau. Wintering at Erie in 1814, she served as a receiving ship there until sunk in Misery Bay in 1820 to preserve her.

She was raised by the Perry Victory Centennial Commission in March 1913, restored, and towed to posts around Lakes Huron and Michigan, returning in September. She then fell into a state of neglect and had to be reconstructed again. The work began in 1929, but halted in 1934 for lack of funds. It was finally completed in 1963 in time for the sesquicentennial celebration of that day in early September 1813 when she and her sisters, and the men who fought them, beat Barclay’s fleet off the Bass Islands in Lake Erie. Niagara is now on the National Register of Historic Places, and can be seen at the foot of State Street in Erie.

Sources Consulted

Berry, James P. The Battle of Lake Erie, September 10, 1813. Franklin Watts, 1970.

Dillion, Richard. We Have Met the Enemy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

Dobbins, W. W. Battle of Lake Erie. Erie, Pa.: Ashby Printing Co., 1876.

Dodge, Robert J. The Battle of Lake Erie. Fostoria, Ohio: Gray Printing Co., 1967.

History of Erie County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: Warner, Beers, 1884.

Lossing, Benson J. Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. New York: Harper, 1868.

Mahan, Alfred T. Sea Power in Its Relation to the War of 1812. Boston: Little, Brown, 1905. 2 vols. (Reprinted 1968 by Greenwood; 1970 by Haskell).

Miller, John. Twentieth Century History of Erie Coutry, Pennsylvania. [n.p] 1909.

National Archives. Letter from Daniel Dobbins to Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton dated December 12, 1812, reporting conditions at Erie and requesting reassurance and help.

National Archives. Records of communications concerning what was done for

Perry, and how supplies were shipped to Erie, covering the period February 1813 to July 1813.

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Conserving Pennsylvania’s Historical Heritage. 1947

Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Pennsylvania and the War of 1812. 1964.

“Perry’s Victory Centennial Souvenir: The Niagara Keepsake.” Journal of American History, VIII:1.1914.

Reed, John Elmer. History of Erie County, Pennsylvania. [n.p] 1925.

Rosenberg, Max. The Building of Perry’s Fleet on Lake Erie, 1812-1813. Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1968.

Salem Massachusetts Gazette, October 1,1813.

Sanford, Laura G. History of Erie Country, Pennsylvania. [n.p] 1894.

Souvenir Program. “Perry’s Victory Centennial, 1813-1913.” Perry’s Victory Centennial Commission, 1913.

Spencer, Herbert Reynolds. Erie: A History. [ n.p], 1962

Weiler, Ruth. Squadron in the Wilderness. n.p 1963.

Whitman, Benjamin. Nelson’s Historical Reference Book of Erie County, Pennsylvania. [n.p], 1896.

Yaple, George Reid. Perry at Erie. [n.p], 1913.