A Naval Historical Foundation Publication, 1 August 1965

ORIGINAL TEXT OF PAMPHLET

“Samoan Hurricane”

By

Rear Admiral L. A. Kimberly, USN

This manuscript on the hurricane that occurred in Samoa on 15, 16, and 17 March 1889, was written by RADM L. A. Kimberly, sometime after the hurricane occurred. Admiral Kimberly, was the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Station at the time, and was embarked in Trenton. All the artwork was done by Admiral Kimberly himself, and for the most part, was copied from photographs taken on the scene. The original manuscript in the Admiral’s own handwriting is in the collections of the Naval Historical Foundation, and is currently on deposit at the Library of Congress.

Admiral Kimberly was appointed a Midshipman on 8 December 1846, graduated from the Naval Academy, and was appointed a Past Midshipman on 8 January 1852. He was Executive Officer of Hartford during the now famous battle of Mobile Bay. He retired from active service on 2 April 1892, and died on 28 January 1902.

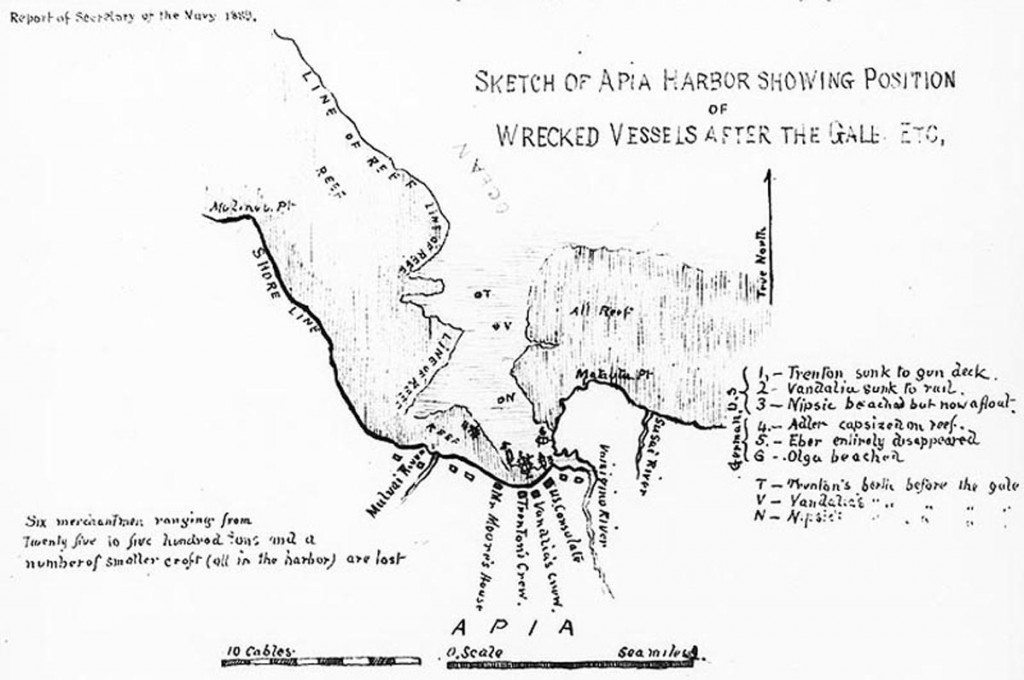

Sketch of Apia Harbor showing Position of Wrecked Vessels after the Gale, Etc, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly, now in the US Navy collection NH 42141.

Introduction

“Our memories are gentle words that flow against the shore line of the long ago. A dim land stretching neath a dim sky, where past events, like ships at anchor lie.”

In these days of surprising changes, events are followed by others in such rapid succession that each later one serves to veil its predecessors with a mantle of obscurity.

This condition fortunately provides a relief to our minds from the increasing burdens that otherwise would overpower them by their multiplicity, and bar the road to future and necessary progress in the pursuit and solving of the manifold problems constantly arising from the advanced conditions of civilization and demands of the present age.

It is well that this is so, for the majority of these can be spared without injury, and some with profit, until they may occasionally be required to elucidate some subject for the edification of an inquiring mind, or the searchings of a future historian.

This is precisely the condition of the report, of a once very interesting, exciting and sorrowful event, in which two powerful nations were involved and indirectly a third, as well as two of its most important colonies, by their sympathies with the nations in the far off South Pacific, and this event, I will read now, has already, in one form or another, been told by others both in song and story. Having been requested several times to give my version of the hurricane that occurred at Apia, Samoa on the 15th, 16th and part of the 17th of March 1889, I comply after a silence of over 7 years. The recital will be as concise as I can make it with due regard to facts. It is as follows:

The Samoan Archipelago consists of four principal islands and quite a number of smaller ones, the intermost is Savaii the largest of all, then east of it is Upolu the most-important one commercially and politically. About 70 or more miles to the east of it lies Tutuila celebrated for its fine harbor of Pago-Pago, and still further on, comes Manua and its adjacent islands.

Savaii, Upolu and Tutuila contain about 7/8 of the whole of the Samoan Territory, about 1400 square miles. Apia, the chief port and Capital of the Group, is situated on the northern coast of Upolu in 13o.59′ S. Lat. And 170o.44′ W. Long. from Greenwich. We now have its Geographical position. The islands are volcanic in origin, are mountainous, and have several extinct volcanoes. The mountains form the back bone of Upolu and other islands, and vary in altitude throughout the group from 2000 feet up to nearly 5000 feet. They are covered with dense vegetation and forests from their summits to the sea. Following the coast line is a belt of level land varying from a few yards to a mile, and in places sometimes more, converse with heavy timber and an undergrowth of an almost impervious character pierced here and there by narrow foot paths leading to the mountains and over them across the islands. It is mostly on this low land and back in the valleys that the majority of the natives live, as they prefer to be near the sea, which to them takes the place of roads, and over which is carried on their traffic. They are splendid canoe-men and in earlier days were bold navigators sailing from one group of islands to another. Coral reefs with breaks here and there in their continuity formed a safe waterway, when a boisterous sea was running outside, and at the same time offered them fine fishing grounds.

The Samoans are physically a fine race of good height, and present almost perfect forms, accompanied by free active movements giving one an idea of how the ancient Greeks might have appeared in the days of Homer.

Their women compare in all respects favorably with the men, are their equal in all family matters. Both sexes are easy in their manners, polite, and very hospitable, and sociable. Their Chiefs are as a rule very able men and their influence is very great over their people and would appear to be derived from heredity. They are usually of a lighter color and larger men than their clansmen.

All are normally Christians School and churches are to be found in nearly every village. Owing to the missionaries, most of the children attend school and can read and write their own language which is remarkably soft and agreeable, owing to the great use of vowels in the formation of their words. Of the Religious sects, the Presbyterians out-number largely the others, after them the Wesleyans and the Roman Catholics. The Mormons also have a foot-hold.

Their character, as compared with Europeans, is childlike. They are communists and have been so for ages. They are very brave, and go to battle with as much zest as our foot-ball teams enter into their contests. In fact, they are more like grown-up, robust boys and girls, delight in excitement, are divided into clans, and greatly respect their chiefs. Their traits and habits account for a great many peculiarities in their intercourse with the whites. The most savage custom they still retain is cutting off the heads of the slain in battle. Like nearly all dark skinned races, they are fond of intoxicants and when under their influence are apt to be quarrelsome. The women then interfere as peacemakers, and successfully as a rule.

The climate is agreeable. Rains are evenly distributed throughout the year, but in January, February, and March heavy rain storms prevail. Destructive storms are rare, occurring at intervals of several or more years.

Before my arrival at Apia, the political status was unsettled and had been so for more than a decade of years. This condition arose particularly from the peculiarities and inherent traits of the Samoan character, and was aggravated by the selfishness, jealousy, interference, and ambition of the foreign residents with the natives – and between themselves.

The prime incentive for these bickerings, especially among the foreigners, was commercial gain, and political preponderance, consequently, the result, as it always has been, and always will be between two races, was the relegation of the native and weaker one, to the grinding surface between the mill-stones. I heard it frequently mentioned by residents, well posted in Samoan affairs, that if the land claims held by foreigners were enforced, the Samoans would be forced into the sea. This probably was an exaggerated statement, but it was an apt expression to define the grasping proclivities that were practiced by the insatiable strangers on the natives. It was rather worse than the fable of the Wolf and the Lamb, or at all events just as bad.

The Nationality most prominently engaged in this pitiable business were the Germans. They were aggressive and energetic in actively furthering their interests in trade and politics. This state of affairs was daily growing worse and more critical. They had so managed affairs that a civil war was inaugurated. One of the Native parties was led by Tamasese, under German auspices. The other by Mataafa, encouraged by the other foreigners. Conflicts that had already taken place inured to the advantage of Mataafa. Laupepa, the rightful King, having been deported by the Germans and retained in captivity until released by the action of the Berlin conference, he might be termed a man of weak character.

We have now a slight idea of Samoa and its people, the group being situated midway on the great-ocean route from California, via Hawaii, to Australia, passing enroute by Tonga and New Zealand, and it is this fact that in the future will decide the question as to whom they will belong. The Native population amounts to nearly 40,000 souls. At Apia the native population varies, the Europeans number 200, included there may be as many as 20 Americans, good, bad and indifferent, in 1889.

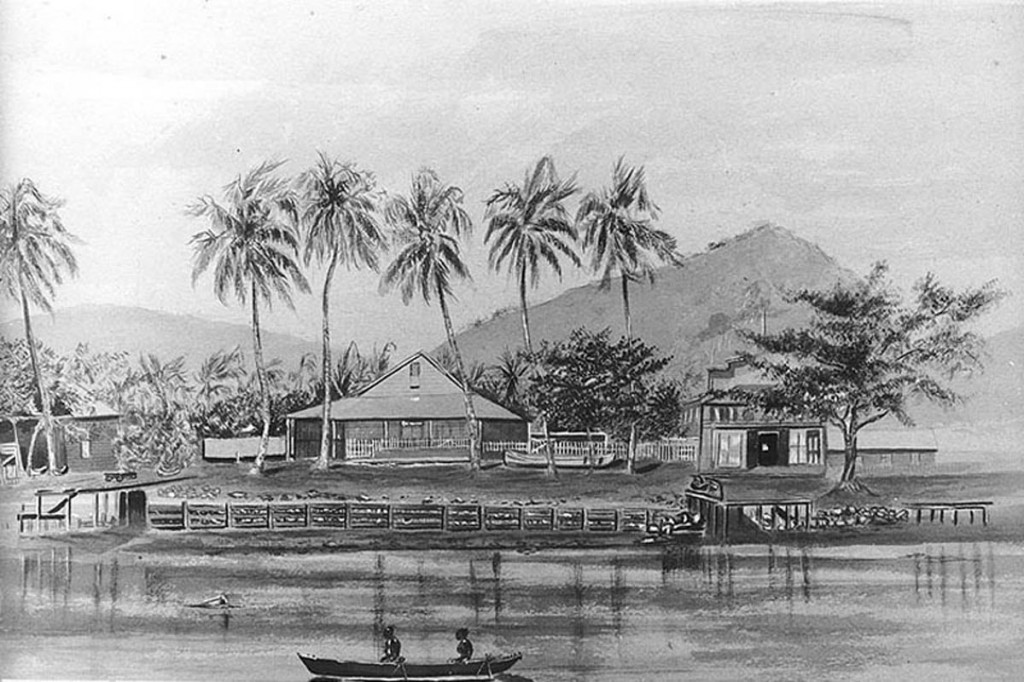

Harbor from Mulinuu Point, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows Apia Harbor, with U.S., German and British warships, and civilian shipping, at anchor prior to the storm. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42115.

Apia facing the Entrance of Harbor, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows a waterfront scene at Apia prior to the storm. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42116.

I will now describe the harbor of Apia where soon, destruction, death and untold misery and suffering were to hold sway, and where man’s efforts amid the awful war of the elements were too puny to alleviate or save.

In approaching the harbor from the sea, you see ahead, stretched out before you, a beautiful green landscape of mountains, hills and valleys all covered with the fleeting shadows of the fluffy trade clouds as they are wafted over the scene to the westward towards Savoii. On the low coast as you approach, the long pendent leaves of the coco palms are swaying to the breeze, their stems overhanging the beach along which the only road in Apia stretches from Matautu point on the east, to Mulinuu on the west. One side of this road is lined with houses, stores, churches and compounds, all facing the bay.

If the tide is high, you see nothing but water right-up to the edge of this road, leaving the roots of the trees that border it. If the tide is low, instead of water you see spread out the flat surface of the coral reef, like a plain with lumps of coral boulders scattered here and there, at times, are surrounded by shallow pools of sea water. This reef extends from the two points Matautu and Mulinuu. I should judge them to be something over a sea mile apart, and where the river Vaisingano debouches, and also the Mulivai, they have cut out the coral from the reef, and this clear space forms the anchorage, as the coral insect ceases work wherever the influence of fresh water is felt.

This space, or anchorage, is in the shape of an irregular letter V with the wide part facing the North and Sea where it is about three cables length in width, from the entrance through the reef to the beach. The anchorage is about 3/4 of a sea-mile in length. In the rainy season the Vaisingano becomes a mountain torrent, that sweeps through the harbor, and out to sea. It was the great amount of water discharged from it that caused in part the strong undertow and whirlpool that cost the lives of so many of Vandalia crew although in ordinary times it brought down along its course, soil that formed here and there in the harbor, patches of good ground. On the occasion of the hurricane, the increase of the mass of its water and force with which it was ejected scoured the bottom of the harbor throughout it extent, leaving nothing but the bare coral bottom, so the anchors had nothing to hold by. This was one of the causes of the ship dragging later on.

Most of the casualties of Vandalia‘s crew occurred close to the beach. In fact, less than a score of yards, for the reason that the accumulation of the ocean’s water rushing in a strong current to the westward and meeting the rivers discharge rendered attempts to crop it abortive, for the swimmers becoming exhausted were sucked into the whirlpool and drowned. It was here that the natives joined hands, and forming a line entered this current to grasp the struggling seamen as they were swept by to inevitable death that awaited them a short distance further on. Some few of them were rescued, but the majority were not, for combined with this mill race of the sea (as it might properly be called) was the heavy surf with its reactive undertow that swept the rescuers off their feet, so their own salvation depended entirely on their off their stalwart arms and firm grip of each one’s hands, that formed the living chain stretching from the shore into this seething and rushing water.

If many of those here lost had remained by their ship, instead of trying to swim this short and treacherous distance to the beach, they would not have lost their lives.

The seven men lost from Nipsic met their fate from being thrown out of a boat that was being lowered after the ship was beached. It is my impression, the boat’s falls got foul and only one end of it dropped. Some of Vandalia‘s men who were trying to reach Nipsic by a line made fast between the two ships, were also lost being jerked off by its sudden taughtening by Nipsic‘s heavy rolling.

Before I proceed further with this narrative, I think it would be well to describe briefly a hurricane.

No man who has not experienced the force of winds and seas in one of these meteors can appreciate their terrific power, but once experienced is never forgotten. There are only two other natural forces that can approach it, and they are an earthquake and tornado. Sometimes both these awful visitations occur at the same time, when this happens, description fails.

So, too, there is much difference in being involved in a cyclone on shore and at sea. In one case you have only the wind and rain to combat, in the other you have not only these but a quivering ship and unstable deck to work your salvation on. Then there is the great storm wave that rises above the surrounding waters, an elevation of the sea which travels on within the center of the storm, submerging everything in its path, where it strikes low land, becoming a flood sweeping everything before it to destruction. A peculiarity of this wave is notwithstanding its elevation above the normal level of the sea engendered by the cyclonic force of howling gusts. Great seas crisscross over its surface adding thereby to its abnormal height, assisted by the demonition of atmospheric pressure that ever is present in the revolving centers of all cyclones and tornadoes, no matter what may be their diameter from yards to miles.

It is a veritable piling of Pelion on Ossa. These great storms vary in their diameters from scores of miles up to hundreds, and more in their centers. There is always a calm region which varies with the diameter of the gale. In this space there is a confused and raging hell of mighty billows, and woe to the craft that is unfortunate enough to be developed within its bounds. Sailors always try to avoid the center.

It is supposed that those cyclones having a greater diameter are not as powerful as those having a lesser one, but, as you approach the center of all of them the winds increase in force, and the seas in confusion as in addition to the gyratory motion of wind, there is also an onward motion.

Still another peculiarity attending them is that they revolve in opposite directions in the Northern and Southern hemispheres, always increasing their distance from the Equator, either North or South as the case may be, from their initiation to their collapse.

On the occasion of the Samoan hurricane, the southern coast of Upolu was struck by the storm wave, which destroyed a stone church and a plantation of 500 coconut trees. As it passed by to the S’d and E’d, its affects were felt on islands over 1300 miles distant from Samoa, if contemporaneous accounts can be credited.

From the time it made its appearance at 3 p.m. on the 15th of March at Apia, until it passed away, was about 40 hours, but not blowing hard all of this time. For 28 hours it blew almost steadily in direction from the NE quadrant of the compass, and finally settled down at North. Consequently blowing right into the harbor, a thing never recorded before. For 12 of those 28 hours, it was blowing with no perceptible abatement of force in the gusts. This was because it was very a slow moving meteor during this time, for it increased in rapidity of movement after clearing the islands, as it was their influence that retarded it. The mountains acting as a barrier to its onward course, as a dam would to a swift running stream. During this storm, the Bar’ fell from 29.60 to 29.19 the lowest reading at 1 p.m. on the 16th. At midnight of that date it slowly rose to 29.52, wind N.N.W. On the afternoon of the 17th the people left the sunken Trenton for the shore.

I more often mention Trenton, because she was the flagship and I was aboard. I narrate only what I saw and experienced, and quoting the reports from the other ships there at the time. All passed through just as severe an ordeal, if not more so, as the number of their casualties and final condition showed after the storm had passed away. The difference being in the longer time the people of Trenton had to endure a torturing and terrible anxiety without hope, and a certainty of the final destruction of their ship, and probably of themselves.

There were many brave acts of individuals and incidents I have not mentioned because they would make this narrative too long, but they were all reported officially to the Department, and are filed for future reference.

I will also state that very serious damage occurred to many of the ships from collisions. The German ship Olga heads the list in this particular. She knocked the smoke-stack out of Nipsic, carried away several of her boats, her rail, main chains, and sprung her mainmast. She struck Trenton twice, taking a quarter gallery off at each blow, at the same time carrying away the starboard quarter davits with their boats. She also damaged Vandalia. She gave much trouble to Calliope. In term of course she sustained much damage herself, losing her bowsprit – close up to the knightheads, and having a hole stove in her quarter, besides other mishaps. She was however the only German ship saved. When hauled off the beach, where she was forced by Trenton, she proceeded to Sidney for repairs. She was not responsible for the damage she did to the other vessels, other what she received, as the storm was master, and worked its will on the ships as easily as if they had been so many chips.

What men could do, was done, but after the elements were unchained, human efforts were unvailing.

I left San Francisco in Dolphin to join Trenton at Panama. On arriving there I shifted my flag to her, and awaited the arrival of stores that had been shipped from New York. Before these stores were received, I was ordered by telegraph to proceed at once to Samoa, to extend full protection and defense to U.S. citizens and U.S. property; consult the U.S. Consul; examine his archives; and otherwise collect information as to the situation, and recent occurrences; protect against subjugation and displacement of Native Government of Samoan Islands by Germany as in violation of positive agreement and understanding between Treaty Powers.

To inform German and British Representatives of my readiness to co-operate in causing treaty rights to be respected, and in restoring peace and order on the basis of recognition of right of Samoan Islands to independence. I was to prevent extreme measures against the Natives of Samoa and procure a peaceful settlement if such arrangement can be made on that basis.

I was to report same for the approval of my Government, and to inform it as soon as possible after my arrival, of condition of affairs, and prospect of peaceful adjustment, and when conflict occurred if Germany was acting impartially between opposing forces.

I was informed in same telegram that the German Government invites the U.S. Government to join in establishing order in Samoa in the interests of all giving assurance of careful respect for our Treaty. The U.S. Government has informed the German Government of willingness to co-operate in Samoan Islands on the basis of full preservation of American Treaty and autonomy of Samoan Islands as recognized and agreed to by Germany, the United States, and England.

The above were the gist of my instructions under which I sailed to carry out in Samoa.

Upon my arrival at Apia, I opened communications with the Consuls, and very much to my surprise, I found that they had received no instructions to co-operate with me, and later on in official conversation with the German Counsul Knappe – he said he was aware of the nature of my instructions, which was a surprise to me at the moment, but it was not strange, as they had become public through the Press, although received by me in cypher.

It was something like playing a game of cards with my opponents knowing what trumps I held.

I thus found if I wished to accomplish my mission, I would have to do it alone. I was not sorry at all for this, as I always believed that there were occasions where one head was preferable to several, and that this case as it then stood, was in this category. I therefore inaugurated a plan of action, and held to it, while I remained in the Islands and which proved successful.

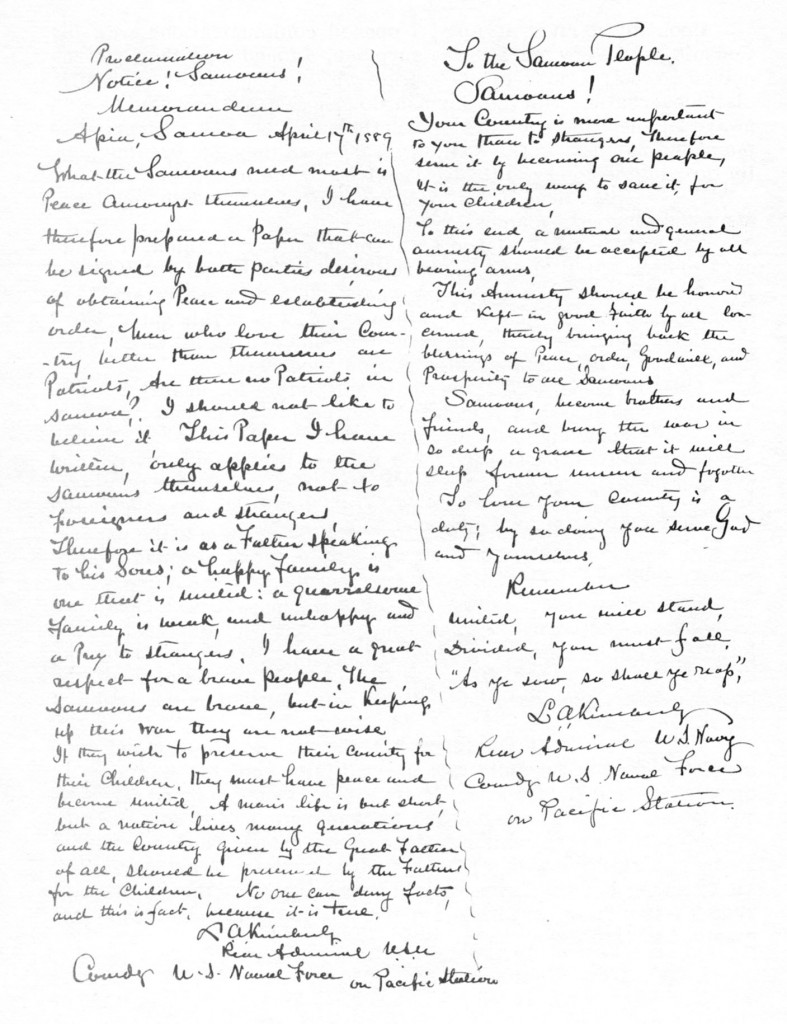

The hurricane and its aftermath delayed me for nearly a month in doing much else than attending to our people encamped on shore, each ship’s company in its own camp. As soon as they had become somewhat settled, I issued to the Samoans – two proclamations, and had them distributed throughout the islands in the Native language, to all in authority, chiefs, consuls, etc. In Apia they were posted on the trees in English and Samoan. I published them in the paper – in fact made them as public as possible. The German Consul thought they would amount to nothing, but the heavens were working. Tamasese – the German Puppet of a King who was encamped at Lotoanuu – acted by German supposed advice, remained in his fortifications, but his force gradually dwindled away so that it was no longer a dangerous factor to the peaceful settlement of the country, which continued until affairs were settled by the action of the Berlin Conference.

Mataafa assisted me all in his power. He commanded 6000 loyal Samoans in the field and in good faith sent his warriors to their homes and fields to plant their crops. Peace reigned throughout the land, which I telegraphed to Washington, and now the foreigners felt the favorable influence of the change, and manifested it – by honoring me with a public dinner previous to my departure, all attending but the Germans. In connection with this, I will now read a letter from the King and from it you can judge his sentiments, and character.

“Mangiangi

Apr 22, 1889

L.A. Kimberly – Admiral of the American Fleet

Your excellency:

I and the chiefs and the counselors of my Government at Mangiangi have consulted together today the 22nd of April 1889. We are highly pleased with the proclamation. The kindness of the Government of the United States is beyond comparison, and I am now able to understand it. Today my desire for war with our kindred at Lotoanuu is finished. I declare the war which was carried on between this part of Samoa, and that part of Samoa is at an end, because I earnestly desire that Samoa should find a state of prosperity, and to give over to you the office of umpire between us both, and let us all work to the same purpose.

Besides, I declare that Samoa would escape danger if the United States alone were to protect and give their support to it and be the sole Master of all Samoa, with the interference of any other power, for in years gone by we have been endeavoring to form a strong Government on the basis of protection of the three powers.

In consequence Samoa has been constantly torn to pieces, and many lives have been lost and the country has been brought down to a very low condtion. On this account we are sure that a recurrence of the triple system should be useless. If now one Power took charge of Samoa and continued to do so forever, then would Samoa for the first time enjoy standing prosperity. I place every hope in your good wishes towards Samoa and hope you will not drawback from them.

May you live

Your Brother in the Lord

Malietuu Mataafa

King of Samoa”

We arrived on the 11th of March at Apia, and being the last ship to arrive before the hurricane, our berth was taken outside of all the other vessels, and not far from the entrance to the harbor. Trenton like the other ships was moored. Next to us, but further in, was Vandalia, then came Nipsic. When I visited this ship the day after my arrival, the officers were congratulating themselves on occupying the best berth in the harbor, because it was the only spot they could find not already taken, where a good muddy bottom could be found for a holding ground. Nearly abreast of Vandalia lay Calliope. Then, the German Olga, Adler, and Eber, in the order mentioned. In addition to the Men of War, there were six merchantmen, ranging from 25 up to 500 tons, and other smaller craft.

We will look back in our minds to where I described the peaceful and calm scene that first struck my view: the day was approaching, when all this was to be changed, when the sea had been placid, with only a ripple here and there caused by the light Trade wind sweeping over the tree crowned shore, struck the waters of the harbor. Soon great ocean’s surges with a clear sweep of more than a thousand miles, were to rise in angry majesty, submerging the low lying reefs under fathoms of water, which rushing onward with maddened speed dashed themselves against shore throwing their spray far inland as carried on the wings of the mighty gale, blighting, withering. I may say scorching all vegetation for over a hundred yards from the beach. On the 12th, 13th of March we had fine weather, a little hazy, but the particularly pleasant. On the 14th the wind was from the south and with rain. On this particular day the barometer began to fall and continued to do so. Then it fluctuated up and down, but with a downward tendency. On the 15th at 3 p.m. the indications of a decided change in the weather for the worse was unmistakable, the wind had been freshening all day blowing from the Sd. off the shore, with no sea.

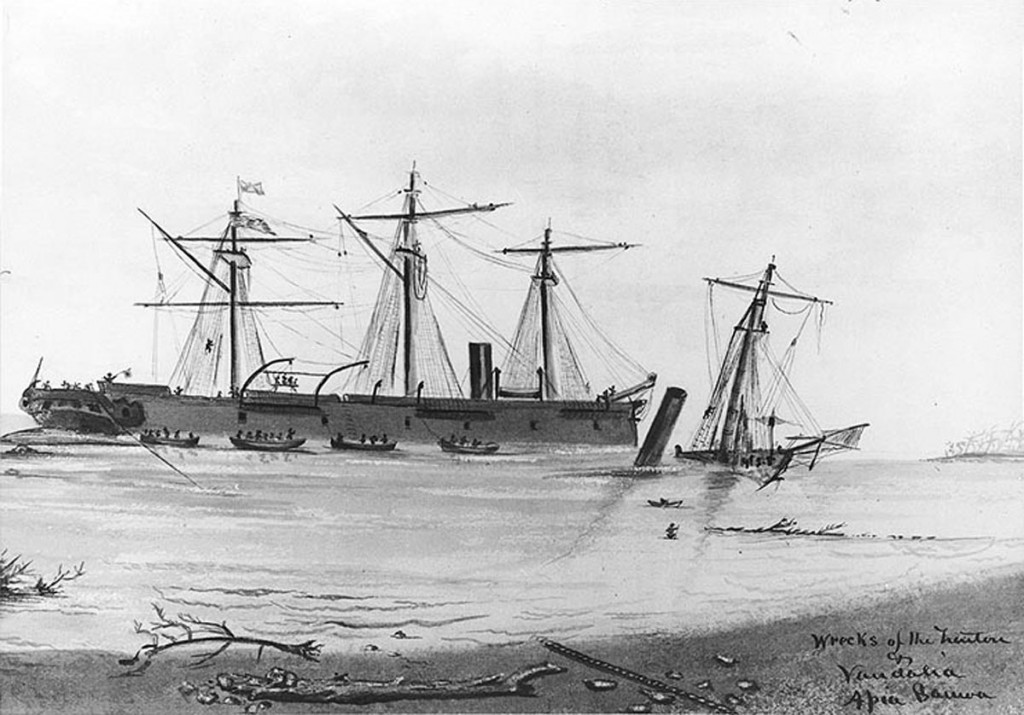

The Nipsic beached, wrecks of Trenton & Vandalia astern, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows the southeastern part of Apia Harbor after the storm’s end. USS Nipsic is in the foreground and USS Vandalia is sunk at right, with USS Trenton wrecked alongside her. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42125.

Lower yards were sent down, and Topmasts housed, steam raised, storm Main and Mizzen staysails were bent. Before the arrival of Trenton there had been three quite heavy gales blowing at Apia and several merchant vessels had been wrecked. The local Pilots and other old residents on shore, supposed the backbone of the seasons bad weather had been broken. All said, that the present indications, judging from the experience of previous years meant only heavy rains, which the fall of the Barometer indicated and that on such conditions of weather at Apia it always fell. This statement and reasoning was satisfactory to many, but not at all so to me, for I also considered that with steam, and four heavy anchors, the top-hamper down, that there would be no trouble, or still less danger to the ship. Besides it would save coal to remain at anchor as nearly all there was to be had at that time was in the ship’s bunkers, as it was a very necessary article to have in case affairs should take such a turn as to require active measures in the future. A hurricane I did not expect, nor did anyone else that I heard of. I did not think that the mud and sand on the bottom of the harbor would be scoured out, and swept to sea. Such a contingency never entered my mind, for this required a local knowledge of the currents under the special conditions then about to take place, which was impossible to acquire in the short space of four days. The Pilots did not know this themselves, or if they did never told it. I did not anticipate with battened down hatches – having water in the hold up the engine room platforms, not that we should lose our steam by having the furnaces flooded, nor that we should lose our rudder and our rudder post. No human being could have foreseen these accidents, nor avoided them under the circumstances, if they had. As bad as it was with Trenton, she was the last one of all the storm battered fleet that remained at anchor to settle down into a wreck.

The Nipsic after being hauled off the beach with jury rudder, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows USS Nipsic as she was fitted during the long voyage from Apia to Honolulu, in May-August 1889. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42129.

The question will no doubt occur to many how it could be known that the bottom of the harbor had been scoured out – clear of mud and sand, leaving the anchors nothing to hold by.

When Nipsic was hauled off the beach, we had to send down divers to find her anchors. In seeing them, they found an inextricable tangle of chains and anchors resting at the bottom of hard smooth coral, as clean as if it had been swept by a broom. Nipsic managed to get the end of one of these submerged chains, but when the anchor came up, after a week’s work, it was found to belong to one of the German vessels and was returned to them after Nipsic reached Honolulu.

I may as well state here, that when she was hauled off the beach, which was done under the superintendence of her Executive Officer, LT Hawley and 150 Samoans, in addition to her own crew, it was found that she had lost her forefoot part of her stem, all of her keel up the garboard streak, her heel up to the propeller casing, her rudder post and rudder. The blades of her propeller were distorted and two of them nearly bent double. Her smoke stack was gone. Her main mast sprung, her rail and main chain plates carried away, and yet, with a jury rudder and smoke stack improvised from Vandalia‘s, under convoy of Alert she arrived safely at Honolulu under the Command of LCDR Henry Lyon (who was the Executive Officer of Trenton, and who was placed in command when Commander Mullan was detached at his own request). The ship was repaired, and finished the remainder of her cruise on the station and was an efficient vessel. Honolulu is 2800 miles from Pago Pago, but the distance covered by Nipsic to reach there was much greater. If any officer deserved promotion for work well done, under the most trying circumstances during and after the hurricane, and in successfully taking a disabled ship such a voyage, superintending her repairs, and volunteering for this arduous duty, it is the officer I have just mentioned. Also in connection with this ship, I will say that Chief Engineer Kiersted, the Fleet engineer volunteered to make the passage in her and rendered the most valuable services both professionally and by example. He also took charge of many of her repairs on reaching Honolulu.

No one knows, unless situated as I was under the circumstances, the relief to mind and heart in having two such men come forward under the inflection of this terrible and sorrowful calamity and give their helpful aid in mitigating such a fearful blow that is seldom the fate of a Commander-in-Chief in any service to experience and which happened for the first time to our Navy, and which I most heartily and sincerely pray may never be the painful fate for any of my professional brothers to experience.

We will now return to Trenton once more. Time, midnight, of the 15th. She was now riding to four anchors, and long scope of chain, with steam to relieve the straining cables, hatches battened down, all hands on deck, men at the wheel. She rode very steadily considering the very heavy seas that were rushing into the wind. They continued to increase in power and magnitude with the wind, and when striking the ship, sheets of water were thrown up from the bows, and borne by the wind over the lower masts heads, then falling on the deck, deluged it faster than the scuppers could free it. At times there must have been a foot or more of water in the spar deck waterways.

The air was filled with foam and spray, both salt and fresh, for in the squalls it was raining in torrents, in the gusts you could not look to windward. The eyes could not bear the pain of the constant piercing spatter. It was hard to catch one’s breath in them at times. On shore people had to protect their eyes and faces by holding up shingles or whatever they could find to keep from being blinded by the drifting sand, driven along by the winds force. And still, the wind must have been greater in power nearer the center of storm than we were experiencing, as it did not pass over us, but out to sea to the N’d and W’d.

This was the condition of affairs when a report came from the main deck that the starboard bridle port was stove in by the sea, killing one of the crew. The damage had to be repaired at once, as the port was about four feet square, and such an opening at such a time meant incalculable danger. It was in a measure repaired, but with great difficulty and danger. Gunner Westfall in his account of this incident, says, “At half past 7 o’clock – I heard the word passed that starboard bridle port, the bow port on the gundeck had been burst in by the sea, and I knew the ship was gone if we did not keep the water out in some way.

I called out for volunteers and went forward. Every plunge the ship made, water came pouring in through a space six feet by four feet, completely flooding the gundeck. I ordered capstan bars and hammocks to be brought at once and we began our fight for life. A capstan bar was needed outside the ship to hold the material that we were using to block the port with, in place. Then I saw that tow tackles must be hooked to the bar so that we could place our barricade out to the port and hold it in place. No one would go to place the straps on the bar and I said, “Well, I will go.” The men begged me not to go, and even tried to hold me back; but I went out at what I thought a favorable opportunity and did the work, but not a moment too soon, as a sea came in as I was being hauled back; and God help me if I had been five seconds late.

Then we got a table and standing it up with both tackles hooked behind, we began to pile hammocks in front, and for five hours we had the most desperate struggle. As every sea came in we would be knocked down and what was worse, some of the barricade would be driven in. Oh God! What discouragement. I didn’t dare to give in, for if I did the men would give up and all would be lost; so we worked on.

After each sea knocked us flat, we would get-up and with cheer make a rush for the barricade, stuffing in mattresses and using capstan bars to ram them home with, and at last we got quite a good barricade built, but still the water came in fearfully. So we built another barricade of lumber abaft the first and forced the water to run out of the water closet chutes and at last, but very little water was going aft.

Now some one says – Mr. Westfall, the ventilator holes are open on the spar deck and the water is pouring down them, so I call Boatswains Mate Gray and asked him if he would go on the forecastle with me and nail some canvas over the hole. We went aft on the gundeck and up on the spar deck and crawled along till we got to our destination and went to work. About one minute afterward we were both struck by a sea, and in five seconds were hurled one hundred feet aft. When I recovered my senses, two men were dragging me out from under a mass of wreckage near the main mast. I tried to stand, no use; the last sea had been too much. I was half drowned and my right foot was hurt.” Thus ended this incident. All of this time the sea was increasing until it had resolved itself into hills and they were trying to turn summersets which they were not very far from doing. At intervals our cables parted one after another until at last we were riding to the starboard sheet anchor with 90 fms. of chain with no abatement of wind, but an increasing sea. We were in a confusion of waters. White foam of breakers around us, the air filled with a misty pall that limited the vision to one hundred yards at times from the ship. As the seas rushed over the reefs with tremulous, the great flood of water piled up against the shore until its mass overcoming the force of the gale spread out and running in a steady stream over the edges of the reefs as a cascade and out to sea, only to return and repeat the operation.

This seaward current was estimated by those on shore to be running at the rate of at least 6 knots per hour within a few feet of the beach.

The wind and seas continuing found Trenton still holding on with her one cable, this was about 3 p.m. on the 16th.

But to go back a few hours, at 7 a.m. our wheel was wrecked with a crash. The two helmsmen were thrown over it and their legs broken and otherwise injured. The cause of this was the breaking of the rudderpost and unshipping of the rudder. Why this happened I never could decide, whether by a blow from the sea from wreckage that was drifting to sea from the inner anchorage, or whether in the interval between two of the mighty seas her heel touched the bottom.

From this time on, we had nothing to control the drift of the ship, but the storm trysails. Water was gaining on the pumps. Before 10 am. our furnace fires were extinguished. We had now to rely on manpower with the main pumps and bailing. We knew when the steam pumps failed, the others would not keep the water down because it was coming through the Hawse pipes faster than they could free her. But to avail ourselves of every chance, to prolong the inevitable moment that was surely approaching, over 400 strong arms in relays worked the brakes to the time of a chanty song of “Knock-a-man down.”

I have a feeling of esteem and reliance of our Blue Jackets when in a tight place, for I never in my active service, which has covered a period of 45 years, in peace, war, or storm, have ever found them wanting. They will dare and do as much as any man if properly led, as any in ancient or modern times. When in this hopeless condition one might – on looking astern into the thick curtain of misty haze, have seen the large black hull of a ship looming forth in the dim distance. It was slowly, very slowly advancing right for us. Now up high in the crest of some sea, and then down so low that only her tops could be seen. It was Calliope taking her chances of being sunk by collisions at her anchors, or running the gauntlet of the reefs for the open sea. Perhaps I could not do better than to give the description, as given by Captain Kane, her Commanding Officer. He says, “The harbor of Apia is as bad a one you care to enter…”.

There was everything to indicate that the gale would be heavier than had been already experienced, and had not implicit faith been placed in all the pilots, and other weather-wise prophets of Apia, every man-o-war would have put to sea early on Friday morning, taking warning by the falling barometer. Another point peculiar to this storm is in the fact that instead of blowing from the N.E. as all previous hurricanes had done, it set in dead from the North, thus exposing the war ships to its full fury.

After sunset on Friday it was impossible to see the reef for the thick weather, and what was worse, it was impossible to see if the vessels were dragging their anchors. As a matter of fact – every ship dragged during the night, for in the morning we all found ourselves considerably in shore, and to make things considerably more dangerous the wind was blowing straight into the harbor. At 5 p.m. Eber which was nearest in, was thrown on the reef and broken into bits for daylight nothing was to be seen of her. Vandalia which had been anchored a long way outside of Calliope before the storm, was dragging down on us. About 7:30 a.m. Nipsic, one of the innermost vessels, went on shore on a bed of sand, and the smart way that the men were leaving her made me conclude that she was breaking up. Only 5 men lost their lives trying to reach the shore, which is creditable to the Captain’s management.

Adler was the next ship astern of Calliope. She touched the reef at 8 o’clock with her stern, just as she did so, the cables were slipped, and almost immediately the vessel was lifted bodily out of the sea onto the reef where she now lies out of smooth water altogether. That will give you some idea of the force of the waves, and the sea that was running. The crew lived on board the wreck from 8 o’clock on Saturday a.m. until Sunday a.m. when they were rescued, all very much knocked about and bruised. These three ships, Adler, Eber, and Nipsic, were thus cleared away, and Calliope was within 20 yards of the reef.

Vandalia now came down on our port bow, the reef being on our port quarter. I could not let my vessel ride to the extent of my cables, with the reef so close astern of me. To move ahead would be to run down Vandalia, and if Olga had gone ahead she would have battered into Calliope.

It was the most ticklish position I was ever in, and without exaggeration, several times Calliope‘s rudder was within six feet of the reef. Had she touched, it would have been all up with us. I had to steer over to get out of the way of Olga, to go ahead to clear the reef, and to slack cables when Vandalia came down on me. At one time the three vessels were locked together, and had it not been for the powerful engines of Calliope, we never would have separated. Not liking the idea of being knocked to pieces, I decided not to remain in this position any longer. There were two courses open. To beach the vessel on the sand, which would save the lives of all on board, but maybe destroy the vessel. The other – to slip the cables and make straight for sea, taking chances of the machinery breaking down, or being powerful enough. I said I would endeavor to save all. Accordingly I slipped the cables and went hard ahead calling up every pound of steam, and every revolution of the screw. In fact, having everything working as hard as they could go. In making the passage, the vessel literally stood on end. The water coming in at the bows as she dipped, running off aft immediately as she rose. I really wondered how the machinery and rudder stood the strain of the tremendous sea that was running. I managed to clear Vandalia without mishap and went so close to Trenton as to put the fore-yard-arm over her deck, and as Calliope lifted up she rolled to port, and the foreyard over Trenton just cleared her. It was as pretty a thing and as lucky an escape as could well be imagined. I just managed to clear the outside reef by some 60 yards. Although I was driving Calliope at the rate of 15 knots an hour, yet such was the force of the wind and sea that she did not make more than half a mile an hour.

Throughout the whole gale nothing affected the crew of Calliope and myself, so much as when passing the American Flag Ship Trenton which was lying helpless, with nothing to guard her from complete destruction, the American Admiral and his men gave us three such ringing cheers that they called forth tears from many of our eyes. They pierced deep into my heart, and I will ever remember that mighty outburst of fellow feeling which I felt came from the bottom of the hearts of the noble and gallant Admiral and her noble sailors. If the Americans stand as nobly to their guns, as they bravely faced that tremendous hurricane, the United States need fear nothing.”

Thus ends Captain Kane’s account.

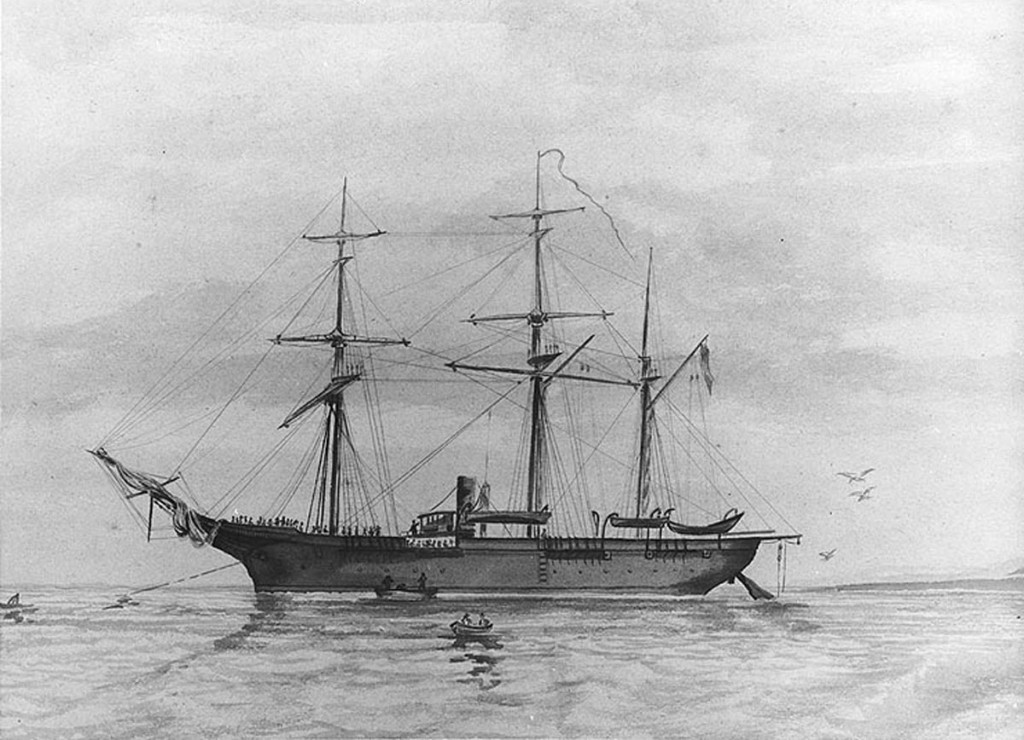

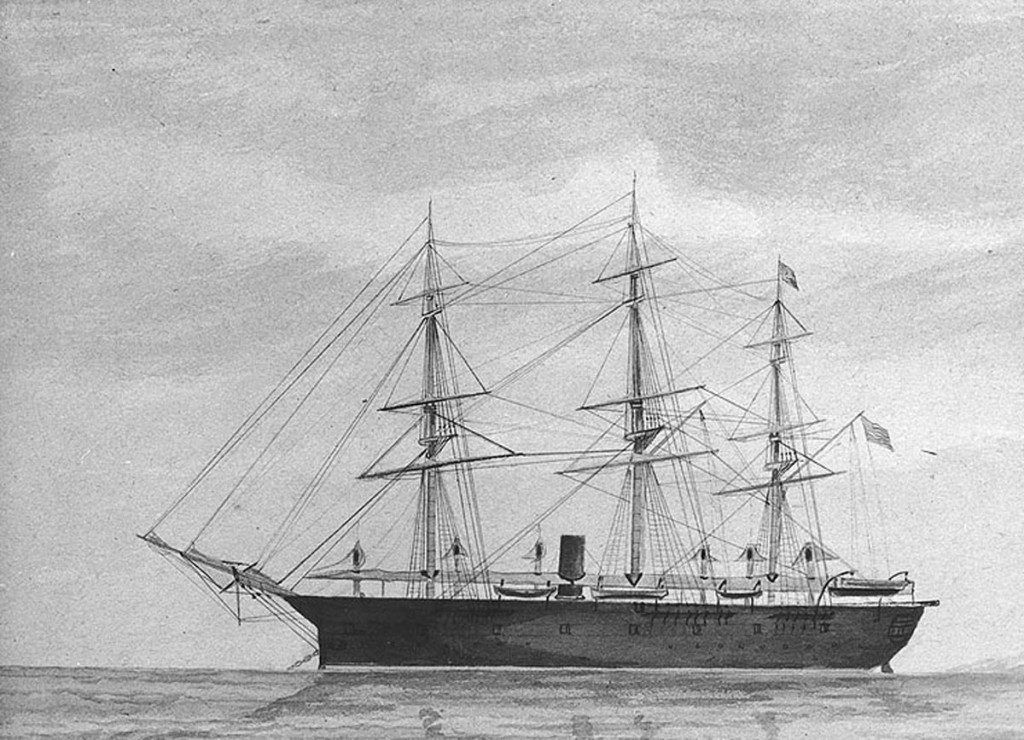

The Trenton before the Hurricane, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows USS Trenton at anchor in Apia Harbor prior to the storm, before she had made heavy weather preparations. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42119.

Wrecks of the Trenton & Vandalia, Apia Samoa, by Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly. It shows USS Vandalia sunk shortly after the storm, with USS Trenton wrecked alongside her. Salvage work has begun on Trenton. Now in the US Navy collection, NH 42133.

But to continue. To me, it was one of the grandest and most exciting sights I ever beheld. There was just room between Trenton and the reef for Calliope to pass. To collide with Trenton or to strike the reef, meant destruction. In the first instance to both ships, in the second, to herself, and as the great plunging, rolling ship staggered through the boiling surf abreast-us, a man on our lower yard arm could have clasped hands with one of hers. A swerve, a yaw of the helpless Trenton at this moment would have been annihilation, but good fortune attended Calliope on that day for she gained the open sea.

It was when her yards lapped ours amidst the war of the elements, that all our long and deep anxiety was turned into admiration for the daring and plucky deed that was passing before our eyes, that then our pent up feelings burst forth into cheers. I will candidly confess, that my extreme anxiety at this supreme moment, made me feel as rigid and as cold as a harp string. As her stern slowly passed our bow, I was so extremely anxious for her safety and success, that I felt by a concentration of mere will, I was helping her seaward.

It was one of the grandest sights a seaman or anyone else ever saw. The lives of 250 souls depended on the hazardous venture. All was staked on this grand endeavor, and they won. It was a victory of mind over matter. The London Telegraph said: “We do not know in all Naval records any sound which makes a finer music upon the ear than the cheer of Trenton‘s men. It was distressed manhood greeting triumph and manhood. The doomed saluting the saved. It was pluckier and more human than any cry ever raised upon the deck of a victorious line of battle-ship. It never can be forgotten, and never must be forgotten by Englishmen speaking of Americans.”

There being no doubt in my mind in regard to our final fate, I said to the Captain: “If we have to go down, let us do so with our flag flying.” He gave the order and our storm ensign was hoisted and remained flying until Olga in her collision with us carried away the halliards and the wind blew in on board of her. It was returned by her Captain after the storm.

The disabled Trenton slowly dragged her laboring way all the remainder of that long, long day to the end of the anchorage, not striking the reefs as she swerved from one side to the other of the harbor, prevented from so doing by the fall and rush of water from their plain like surface which acted as an off set from them. This action was a constant one, as they were submerged by every wave many feet deep, and as water will always find its level, this was the only way it could do so.

But this principal and natural cause and force on which the safety of our lives depended in a great measure was either not understood, or not appreciated, at least by one of our officers, and consequently it remains for me, in a paper of this character, to correct – once and for all, an impression, or statement, that appeared in the public press and bulletins throughout the land at that time. They stated, why I do not know, that he saved all hands on board of Trenton by his exceptional seamanship by keeping the ship off the reefs, by working the storm trysails and manning the mizzen shrouds.

In the House of Representatives of the 54th Congress, a member at this late day, brought in a bill to promote him to the grade of Commander on the retired list for jumping overboard with a line, by which all were to be saved, when in fact no such act took place as he never left the deck.

This officer, then Lieutenant and Navigator, being Officer of the Deck at the time, has probably forgotten in his desire for fame and promotion, that if his uncalled for and pressing request and advice had been followed, to slip our last cable when the ships taffrail was overhanging the reef, not a soul would have been saved to tell the tale. To have complied therewith would have been very bad seamanship under the circumstances, and his appeal for promotion for saving all of us by working those sails and manning the mizzen shrouds, which is a very old idea, and understood by all midshipmen as a question often given at their seamanship examination, would never have been made.

It is marvelous how the lapse of time will incubate hallucinations in some minds. It must strike my professional brethren as ridiculous for an Officer of the Deck to arrogate to himself the power to do this or that in the immediate presence of his Captain, to say nothing of his Commander-in-Chief when both were on the bridge from whom all orders were either issued or permitted, as they alone were responsible for what was done.

In all cases where the Captain of a ship is on deck, the Officer-in-Charge is considered his mouth piece. This is and always will be. It is because the Commanding Officer is always on duty, and cannot, if he would, divest himself of responsibility. It is the Law, the Custom, the Etiquette of the Naval Service and is founded by experience from time immemorial.

The Captain in his report dated March 19th, 1889, in the latter part of it says, “Lieutenant R.M.G. Brown, the Navigator, was by my side the whole time, and to his excellent judgment, one time at least, the ship was cleared of a reef. Had we struck it I fear few of the 450 people onboard of Trenton would be alive today.”

This quotation from Captain Farquhar’s report, I think was the basis on which the Lieutenant’s application for promotion rests. I take it for granted that when the Captain made that report, that such was his opinion, but I do not agree with such an opinion. In justice to Lieutenant Brown I will heartily acknowledge that he was zealous in the discharge of his duty, he was bound to be so. So were other officers and men. Promotions should only be given for valor or for great exceptional services. When it is sought publicly by personally proclaiming one’s acts, backed by an inordinate desire for notoriety, it should be withheld. Cold calculating selfishness where so many were performing their duty zealously and ably should be discouraged. Our Naval Service demands that in all things, her sons shall bear Honor as the first and brightest virtue, for without it all else is naught.

Everything has an ending, so did the long arduous struggle for the grand old ship. After pounding on the hard coral bottom she gradually brought-up and gave up her life forever alongside of her submerged sister, Vandalia, whose masts, bowsprit and forecastle were the only visible parts left above water. Her lower rigging and tops were crowded with her crew and officers. Now, our great case was to rescue them before her masts went by the board. This was successfully accomplished by sending rockets with lines attached, thereby establishing an effective means of communication between the two vessels. All that remained of her crew were placed in safety on the decks of Trenton, where they remained until the subsidence of the storm after which they were transferred under the command of her officers to quarters on shore. They lost everything but the clothes they stood in. Many used their shirts to wrap around the sharp ratlines to relieve the pain of standing so long on their feet.

Lieutenant Carlin in his report states, “We slipped the sheet chain to avoid fouling Olga‘s ground tackle, and veered on both bowers to clear the ship herself. After passing Olga we made strenuous exertions to bring her head to the wind, but they were of no avail, and the stern took the inner point of the reef at 10:45 a.m. Sunday. The engines were kept going until we were convinced that the ship was hard and fast. They were then stopped, safety valves opened, and the firemen called on deck. The ship’s head swung slowly to starboard. She began to fill and settle, and the rail was soon awash, the seas sweeping over her at a height of 15 feet above the rail. We were within 200 yards of the shore, but the current was so strong and the seas so high that swimming was a reckless undertaking.” The Lieutenant in closing his report says, “This does not complete the list of gallant acts and brave men, danger and suffering have effaced from the memory many deeds of valor and it is claimed for the men in general that their conduct before, during and after the gale, will bear the closest inspection, and now that the lips of their gallant Commander are closed forever, the Executive Officer raises his voice in their behalf, and with the earnest hope that, as they have left a clean wake, they may have a fair wind in all time to come, and that they may encounter only the waves of prosperity in their course.” This letter was written to the Secretary of the Navy, from San Francisco, and was endorsed by the Commandant of Mare Island thus, “Lieutenant Carlin showed himself a worthy leader of brave men.”

The Captain’s body, some days after the gale, was recovered five miles down the coast and interned temporarily on a German plantation nearby. This shows the force of the current setting out of the harbor and down the coast between the reefs. Lieutenant Carlin, who was a man of splendid physique, endeavored to save the Captain, but the Captain, from an injury previously received was too weak to help himself, otherwise he too might have reached the rigging. Vandalia lost 43 all told, Nipsic 7, Eber 76, Adler 20, and Trenton one. This does not include the wounded. We established our hospital at first in a Church, and afterwards in a school house, both offered to us by the kindness of the missionaries of the London Missionary Society.

Whilst drifting down the harbor, we used oil by pouring it from head chutes, to keep the seas from breaking – it did very little good to Trenton, but as it traveled shoreward, its effect observed and remarked by some on board Vandalia as beneficial.

After the crews of the vessels had reached the shore and were engaged in preparing their camps, Mataafa offered to have all the native houses in the vicinity vacated for our use. This kind offer was declined for the reason that the men would have been too much scattered to be under proper control, which was necessary that they should have considering the situation.

I will now close this narrative, by reading a part of the Navy Department’s letter to me – in answer to my official report of the Catastrophe, with a request for a Court of Inquiry.

It is dated April 27, 1889. This the quotation therefrom:

“Sir:… In reply to your request and that of Captain Farquhar for a Court of Inquiry, the Department has to say, that it deems such a Court unnecessary. It is satisfied that the Officers in the Command of ships at Apia, did their duty with courage, fidelity, and sound judgment and that they were zealously and loyally seconded by their subordinates; that the hurricane which caused the destruction of the vessels, and the loss of so many lives, was one of the visitations of Providence in the presence of which human efforts are of little avail; that the measures actually taken by yourself and the officers under you were all that wisdom and prudence could dictate, and that it was due to these measures that so large a portion of the crews were saved; that the one step that might have averted the catastrophe, namely to have put to sea before the storm had developed, could only have been justified in view of the great responsibilities resting upon you at Samoa, by the certainty of overwhelming danger to your fleet, which could not have been foreseen.

That you rightly decided to remain at your post and that the Department, even in the face of the terrible disaster which it involved approves absolutely your decision, which has set an example to the Navy that never should be forgotten.

To convene a Court of Inquiry under the circumstances would seem to imply a doubt on the part of the Department, when no doubt exists, and instead of ordering an investigation, it tenders to you and through you to the officers and men under your command, its sympathies for the exposures and hardships you have encountered, and its profound thanks for the fidelity with which you performed your duty in a crisis of appalling danger.

Signed by: B.F. Tracy

Secretary of the Navy

To: RADM L.A. Kimberly, Commander US Naval Force,

Pacific Station

“THE MEN OF THE TRENTON”

Respectfully offered to Rear Admiral Lewis A. Kimberly, U. S. Navy

New York, March 15th, 1890 by John Malone

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Through the black hurricane hear

The hearty English Cheer!

Defiance to death and fear;

By half a thousand throats out-thrown,

From the decks of the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

‘Tis the salvo of the stars

To Saint George’s crossed bars,

As the sturdy British Tars

Steer their ship into the arms of the Storm,

Slowly past the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Hearts that beat ‘neath Berserk shields,

Hearts that crimsoned holy fields;

Bore, of old, the blood that yields;

That brother – hail of death doomed valor

From the men of the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Sea-Eagles of the Elder strain

The Saxon, Gall, Scot, Norse and Dane

Were mated in War’s bloody rain

And we, their brood, join death-song greetings

With our brothers of the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Clontarf, Culloden, Fontenoy

The battle-blasts where the alloy

Was forged, which Kings cannot destroy

To the stern music of the song we chant

With the men of the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

How the brave tongues gave bay

From Lucknow, Balaklava and the gray

War dusk of Nelson’s glorious day!

And their echos out-thunder the wild sea’s thunder

Around the helpless “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Breast to breast in the New Eggle-Land

We smot each other with steel-clad hand,

And the blows but-toughened the welded bond

Theat ties our hearts, brave lads, to yours,

Brave lads on board the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Ye had your fiery trial too,

When your fathers in gray and your fathers in blue

Laid their hat brows in the glory dew

That their sons might be shoulder to shoulder today

‘Neath the starry flag of the “Trenton”

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Whatever the fate that betides ye,

God and Saint-George abide ye!

Though we leave ye, we fondly confide ye

To the kindred love of the age unborn,

Heroic hearts of the “Trenton”