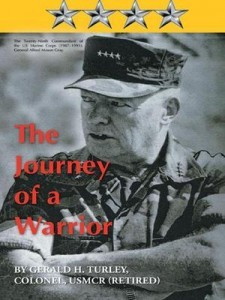

By Col. Gerald H. Turley, USMCR (Ret.), IUniverse, Inc., (2012).

By Col. Gerald H. Turley, USMCR (Ret.), IUniverse, Inc., (2012).

Reviewed by John Grady

The Journey of a Warrior is a “friend’s book.” Gerald Turley has known, respected, and worked with and for Al Gray for years. That is both the book’s greatest strength and a weakness. As he wrote, “Again, this is not a biography. Rather, it is an effort to capture the picture ‘before the colors,’ face based on my personal observations and those who were close to General Gray during the later stages of his career.”

I had the good fortune to serve as managing editor of Navy Times during Gray’s tenure as commandant from 1987 to 1991. Those were exciting times to be covering the naval services – the aftermath of John Lehman’s controversial stint as Navy secretary; the 600-ship Navy; homeporting, etc.; Jim Webb’s integrity during his all-too short time as secretary in a budgetary showdown; and Gray’s overhaul of the Marine Corps way of thinking, equipping, training, and fighting.

I remember how surprised the reporters who covered the Marine Corps for the newspaper were by Gray’s very late-in-the-day selection as commandant. As Turley recounted in detail, the senior leadership of the Marine Corps itself, especially those in and around the Pentagon and Navy Annex, were as well. To them, he was too old. “They thought he had the wrong image for the Corps at that time of a rapidly declining defense budget.” Adding, “Secretary Webb’s announcement was so surprising that no temporary government quarters had been arranged for a new four-star general officer who was not already living in the local area.”

Gray prospered in a career outside of Washington that sharpened his insights into the value of maneuver warfare and educating – thinking strategically, not just tactically and building a true Marine Corps University — and training Marines of every rank – Basic Warrior Training and recreating the School of Infantry. Oh how, Rep. Ike Skelton, D-Mo., and a powerful member of the House Armed Services Committee, loved this. This was the kind of professional military education that Skelton envisioned complementing Goldwater-Nichols.

As commandant, Gray was constantly on the move, putting the lie to the whisperers who claimed that the pace of a commandant’s life was so strenuous that it would wear him down. As Turley noted, the time was so short between his nomination and the change of command he didn’t issue a new “Commandant’s Guidance.” Instead he “elected to be his own messenger” in sharing his “warrior philosophy” and shaping the new Fleet Marine Force Manual 1, Warfighting.

Phrases such as “Special Operations Capable” and acronyms like MAGTF [Marine Corps Air-Ground Task Force] became commonplace in papers, presentations, conversations, testimony and were also coming into practice.

The commandant also fared extremely well in Congress in explaining the Marine Corps needs then and for the future. He became a master at documenting its needs for “supplementary appropriations.” He won critical support on Capitol Hill and the E-Ring of the Pentagon for the Light Armored Vehicle, the tilt-rotor V-22 Osprey, and air cushioned LCAC, the Marine heart of the “gator fleet” with its new class of amphibious assault ships. In his 1988 Marine Corps Posture Statement, he wrote, “We are leaner, more mobile, and more expeditionary. If asked, we could go to war now.” Less than three years later, they were at war and performed superbly. Turley does an excellent job of explaining how Gray’s attention to detail and concern for “his Marines” paid off.

From the start, Gray demanded the Marine Corps senior officers have “fire in the belly,” and Turley described how effective he was in clearing out the “no vacancy” problem at the senior level to rejuvenate the whole force. “During Gray’s first year in office, more than twenty generals would retire.” The Special Early Retirement Board reviewed the records of serving colonels and a number of them including “several of General Gray’s longtime members of his professional groups.”

Gray probably struggled longest over what role women should play in the Marine Corps. In this area, he also was at odds with the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services [DACOWITS] who were recommending that more and more fields be opened to women, some extremely close to the law barring them from direct ground combat. He created a task force to review the situation, and its report and the steps Gray took is well summarized by Turley.

In summary, “General Gray did indeed have a vision. It was to prepare the Marine Corps operating forces against the emerging terrorist threats of the twenty-first century,” Turley wrote.

This “friend’s book” makes a strong case for those two sentences.

John Grady conducts oral history interviews for the Naval Historical Foundation.