Reviewed by Dr. Richard P. Hallion

Mention “Stearman” among any group of aviation aficionados and an instant image of one of history’s most influential and appealing aircraft comes to mind. The Stearman biplane occupies a unique place in the pantheon of American aviation, having produced, through its widespread use as a primary trainer, hundreds of thousands of Allied pilots before and during the Second World War. Afterwards it gradually gave way to more modern monoplanes, but found new life as an agricultural sprayer, and even a measure of cinematic fame as the murderous strafer chasing Cary Grant through the cornfields of Alfred Hitchcock’s iconic North by Northwest. Today, nearly eight decades after its first flight, the “Yellow Peril” is readily sighted cavorting at air shows, and some still ply their trade as trainers, sailplane tugs, and crop-dusters.

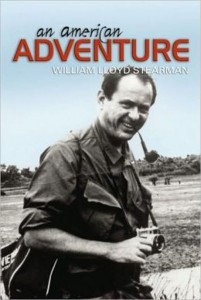

William Lloyd Stearman is son of the trainer’s legendary creator, Lloyd Stearman, and his book is at once both a hommage to his father and a fascinating accounting of his own remarkable life and the tumultuous times in which he lived. Stearman père was a brilliant designer, though less successful as a businessman (he was, in fact, at one point dethroned by a scheming associate from leadership of his own company). In 1924, he introduced young William to flight as the tender age of 22 months, holding him in his lap as he flew one of his first designs. Stearman fils ably traces his father’s contributions to aviation and his role establishing America’s aircraft industry during the interwar years. He offers many revealing insights both about his father and many other early aviator-entrepreneurs whose work collectively rescued American aviation from its doldrums in 1919, reshaping and elevating it to global prominence less than two decades later.

But the book’s primary focus is the son. As a witness to history, William Stearman’s life rivals the fictional Forrest Gump: a young naval officer aboard a LSM during the great Pacific amphibious invasions of 1944-45, landing troops and supplies under fire, facing enemy bombs, shells, and the occasional Kamikazes; lieutenant (senior grade) skipper shepherding a war-weary breakdown-prone heavily loaded ship on a perilous return from the far Pacific back to the United States, and through the Panama Canal to Charleston; multilingual graduate student on the GI Bill in Switzerland after the Second World War; Foreign Service Officer in Austria and Germany in the early (and occasionally deadly) days of the postwar US-Soviet confrontation, including a front-row seat at the Hungarian revolution; with President John F. Kennedy during his disastrous meeting with Khrushchev in June 1961; official traveler through Eastern Europe, avoiding various compromise and kidnap schemes by Soviet Bloc security services; foreign service in South Vietnam in the critical years from just after the murder of Ngo Dinh Diem to just before the Tet offensive; Nixon-era National Security Council staffer during the era of Vietnamization, and the North Vietnamese Spring Invasion of 1972; witness to the latter days of the Nixon Presidency and the Byzantine Ford transition (“Apart from combat, this was the most surreal event in my life.”[201]); strategist at the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency; Professor of International Affairs at Georgetown University; a return to the NSC in the heady Reagan era and the final days of the Cold War; appointment as a Papal Knight of the Holy Sepulchre.

Stearman is proud of his many accomplishments, but the great strength of the book is that he is equally frank about decisions and beliefs that proved flawed or less than perceptive. Unlike many, he does not use the autobiographical genre to engage in petty sniping and self-serving score-settling or justification, and he shows an admirable regard for citing professional histories and other sources to buttress his arguments or to otherwise inform his narrative. The book has some minor stylistic flaws-occasional repetition of phrasing and references, and some small errors of fact that more careful review should have caught (Billy Mitchell, for example, did not use 1,500 bombers to sink the Ostfriesland [240]).

Stearman is blunt in his judgments, and though personally and politically strongly conservative, is no reflexive zealot. He is an astute observer of American-European relations, seeing much merit (and also weaknesses) in the social and cultural values of both, but believing that America’s empowerment of the individual and “genuine religiosity” makes it unique among the world’s nations [162-64]. Like many, he believes that after 1973 American politicians and bureaucratic careerists threw away the opportunity to preserve South Vietnam, but sees that loss as rooted in much earlier failures, beginning with the Kennedy administration’s complicity in the overthrow of Diem in 1963 [194-97]. Although not a “battleship sailor,” he has an abiding fascination for the big vessels from his time as a young amphibious assaulter, and argues energetically (and more persuasively than many other advocates) that their retirement as littoral fire support systems constituted a blunder of great potential consequence [239-52].

Overall, An American Adventure is a very informative, even entertaining work, offering much that historians of naval operations in the Second World War, Cold War historians, students of the Vietnam experience, and those interested in more recent foreign policy and national security studies will find of value. It offers a valuable “view from the trenches” perspective complementing (and counterpointing) other memoirs of notable Cold Warriors such as Paul H. Nitze’s From Hiroshima to Glasnost.One leaves this work thankful that its author took the time and effort to write it, and that others-particularly Dr. Stephen T. Hosmer of The RAND Corporation-encouraged his literary efforts, steering him to the Naval Institute Press (which is to be commended for publishing what is, overall, an unusually fine and fascinating book).

Dr. Hallion is Research Associate in Aeronautics, at the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Nancy J Cullen