Compiled and edited by Dr. Fred Allison and Colonel Kurtis Wheeler USMCR, US Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA (2012).

Compiled and edited by Dr. Fred Allison and Colonel Kurtis Wheeler USMCR, US Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA (2012).

Reviewed by Colonel Curt Marsh, USMCR (Retired)

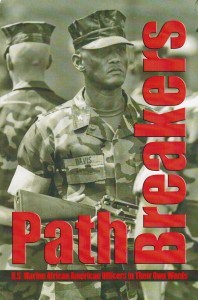

Path Breakers is a worthy addition to the story of the ongoing struggle by the Marine Corps to address diversity and build an officer corps that is more representative of the general United States population. The introduction points out that there have been other books written specifically about the history of African Americans in the Marine Corps. This book takes a different approach by compiling a collection of interviews conducted with a variety of African American Marine officers. The interviews and comments are presented in chronological format that provides a history in itself but with a uniquely personal perspective. Lt. Gen. Walter Gaskin led the initiative to develop this book, primarily as a means to help promote minority officers in the Corps. He noted that the purpose of this book is to educate people, specifically prospective African Americans officers, on how previous African American officers navigated their way through successful careers in the Marine Corps.

I was personally intrigued by this book since I knew several of the officers who were interviewed for the book. I have worked with and for a number of them including Lt. Gen. Gaskin who was a contemporary of mine at HQ Marine Corps. Like personal stories from combat, everyone has a little bit different perspective on what happened, but these stories present the unique perspective of being African American or “black” in a majority white culture. Part of the take away is how the race issue in the Marine Corps has changed over the years. Although many blacks served as Marines in World War II in restricted fields, there were no black officers until after the war. One of the enduring issues is the challenge of growing the number of minority and specifically black officers in an organization that generally reflects a majority white culture. This is not to say that the Marine Corps or the officer corps is racist any more, but that there are enough cultural differences that most minorities face additional challenges adapting to the new culture on top of becoming Marines. All of the interviewees are great proponents of the Marine Corps but do not pull punches when noting the challenges they faced along the way in their careers.

Each of the interviewees addressed where they came from and the challenges they faced along the way both prior to and after joining the Corps. It provides an interesting view of the black community experience which is very different from the typical “middle class white” experience. There are a number of engaging and often humorous stories of racial based challenges. They tell of how they personally dealt with these situations, but a key issue was how other Marines, both black and white, stepped up to help taking care of each other. One observation is how racism in the Corps shifted over time. Through the 50s and into the 60s racism was mostly institutional with policies coming out of HQMC. Into the 70s and beyond HQMC shifted to promoting minority officer policies. Another observation is how Marines looked out for each other on the local unit level, in spite of racism in the community, which was a major issue up through the 60’s with many bases located in the old south.

There is a good deal of discussion on how to recruit and retain minority officers. The focus of recruiting is primarily on educated success oriented, minority individuals who are also highly valued by business and other organizations. The challenge is on how you can identify the few select individuals out of this group who have the potential to be Marine officers. Then how do you make them into Marines and retain them for a full career? It was pointed out that the Marine Corps has not been a popular career pursuit in the black community, particularly compared to the Army and more recently, the business community. Partly it is a perception of the Marine Corps as the most conservative of all the services, but often it is just a lack of knowledge in the minority community of what the Corps provides.

I was waiting for some discussion on affirmative action, but this is not a major issue in the book. Each of these officers has been successful in their careers and rightly believes that they have earned the rank and honors they have received. Lt. Gen. Gaskins points out that it takes 22 years or more to make a Marine Colonel. To be eligible, that officer must have pursued and succeeded in certain command positions and should have completed appropriate military education. This is true of any officer promotable to senior rank. Accordingly, he proposes that minority and specifically African American officers need to be mentored along the way to know what is expected of them and to maneuver through the various challenges faced throughout a normal career.

I highly recommend this book to those interested in promoting the worthy goal of diversity in the officer ranks of the Marine Corps. It provides an enlightened and informed perspective on how this may be accomplished and that it is an ongoing challenge. Policies from the top down need to be fair and equitable to officers of all ethnic background. Prospective minority officers need to know that they will be treated fairly in the Corps, but they also carry the responsibility to do their best to compete and succeed throughout a career. The “Path Breakers” in this book all believe that leading Marines is a special privilege and hope that more minority officers can continue to follow in their footsteps.

Colonel Marsh is a frequent contributor to Naval History Book Reviews.

Clarence L. Baker

Stephen M. Jackson, CMDCM(SW/AW), U.S. Navy (ret.)