Reviewed by Dr. John. R. Satterfield.

In the early evening on July 19, 1545, as she turned away from a French fleet gathered in the Solent, the narrow channel between the Isle of Wight and the English mainland harbors of Portsmouth and Southampton, the Mary Rose, one of Henry VIII‘s largest and most powerful warships, heeled to starboard in a gust of wind and promptly sank.

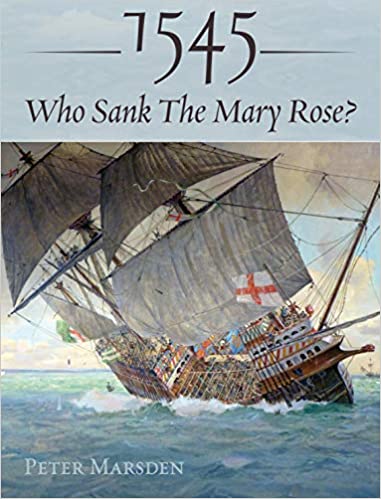

The ship, a carrack, carried four masts with nine or ten square-rigged and lateen sails. She carried more than 90 guns, large and small. The ship, rebuilt in 1536, added tall, three-level fore and aft castles to accommodate more than 500 ship handlers, archers and soldiers who boarded enemy vessels in close combat. These structures, and new great guns, added about 200 tons to the ship’s original 500-ton displacement. Gun ports cut into the hull for large weapons created openings only 16 inches above the waterline when fully laden. The only contemporary illustration of Mary Rose (without realistic perspective), shows the immense castles, with the forecastle extending well beyond the hull’s stem. Likely dimensions indicate the hull at the waterline was about 130 ft. in length, with a beam of about 39 ft. Castles added another 25 ft or so to the length overall, not counting the bowsprit. To an untrained eye, the ship looks dangerously top heavy, with parlous balance. The ship had served more than 20 years before its refit without incident, but apparently saw little action until war with France in 1544. French King Francis I assembled a large fleet to attack the Isle of Wight and southern England in retaliation for Henry’s capture of Boulogne that year.

Mary Rose vanished in seconds, taking most of her crew with her. Only her masts and crow’s nests remained above the surface, and only about 40 men survived. Henry VIII saw it all from Portsmouth. Salvage efforts and inquiries quickly followed, but failed. The Mary Rose remained on the sea floor, slowly vanishing from view and largely undisturbed

In 1971, diving historian Alexander McKee rediscovered the ship after searching for several years. Remarkably, a team of maritime archeologists, including author Peter Marsden, long affiliated with the ship, its recovery and restoration, found that silt covered about a third of the ship’s hull, preserving it erosion and rot.

Marsden devotes most of this wonderful book, beautifully illustrated with many color photos and excellent graphics, to the technical aspects of Mary Rose, its recovery, itself remarkable, and its preservation. Today, after decades of careful treatment, about a third of the original structure consisting of the starboard hull and amidships, has been fully preserved. Both fore and stern castle are gone, long destroyed with the port hull because they were not buried in silt.

Just as remarkable, however, are thousands of artifacts that survived – guns and carriages, small arms including long bows, leather and some fabric clothing, shoes, tools, tackle, dinner plates and eating utensils, navigation instruments, storage trunks and barrels, and the skeleton of the ship’s dog! In addition, excavation yielded 179 human skeletons, many nearly complete. Sophisticate forensic analysis has provided astonishing evidence about the crew, men who hailed from Europe and Africa as well as England. From these data, Marsden reconstructs the lives and last moments of soldiers, archers and ordinary seamen, deck by deck, in Tudor England’s Navy Royal.

As the title suggests, however, Marsden’s basic purpose is to determine who was responsible for the loss of Mary Rose. Research has revealed the sequence of events that destroyed the ship, but why did this happen? Marsden is quite clear; the fault lies with Henry VIII himself. The king failed to understand the ship’s limited capabilities. The Mary Rose was built for close combat, for archers with longbows and soldiers who boarded enemy vessels for hand to hand fighting. In the 17th century, new ship designs, known as ships of the line (such as Admiral Nelson’s Trafalgar flagship, HMS Victory, in drydock just steps from the Mary Rose Museum) evolved. Ships of the line were sleek, efficient and stable, built for great gun engagements with broadsides at some distance. Henry’s failure to adapt the carrack for this transition cost the lives of about 500 of his subjects.

Peter Marsden, 1545: Who Sank the Mary Rose? Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, U.K. (2019 (Harbound))

Reviewed by Dr. John R. Satterfield. Dr. Satterfield teaches military history and business. He served as an ASW intelligence officer in a USNR maritime patrol squadron. He recently contributed to From Across the Sea: North Americans in Nelson’s Navy, available from Helion & Company, Warwick, UK.

Purchase your copy today! amzn.to/2YyT8ig