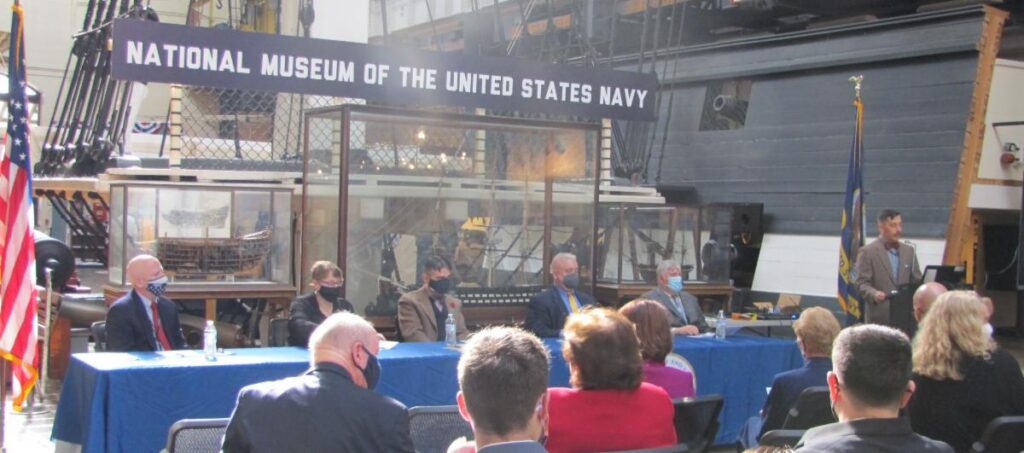

Right to Left: Master of Ceremonies Tom Frezza, Moderator David Winkler, Panelist Chris Havern, Panelist Lucas Clawson, Panelist Kara Newcomer, and Panelist Scott Price

Senior historians of the sea services conversed in the National Museum of the United States Navy on Tuesday, ahead of a ceremony commemorating the centennial of the Unknown Soldier’s arrival at the Washington Navy yard with a new plaque.

The initial impetus for the installation of a plaque on the Washington Navy Yard came from the Society of the Honor Guard, represented at Tuesday’s ceremony by its President Gavin L. McIlvenna, and the event was arranged by the Navy History and Heritage Command.

In his opening remarks, RADM Sam Cox, Director of the NHHC, noted the pertinence of studying the First World War, which resulted in loss of life unprecedented in the western world, compounded by the outbreak of the Spanish Influenza in 1918 which, much like the war, disproportionately affected the young and healthy. The United States was unique in undertaking the daunting task of repatriating the remains of its fallen soldiers, though the British and French were first to adopt the tradition of an unknown soldier.

Acting as the moderator for the discussion, NHF historian Dr. David Winkler noted that ADM William Ledyard Rodgers—the Naval Historical Foundation’s longest serving president with a tenure of 26 years lasting from 1927 to 1943—was passionate about preserving the Olympia, which Dr. Winkler himself would go on to use as a potent tool for recruiting new naval personnel in Philadelphia, where Olympia continues to draws visitors to the Independence Seaport Museum.

NHHC Historian Chris Havern remarked that the choice of the USS Olympia to bring the Unknown Soldier home may be best attributed to the great fame it earned as Admiral Dewey’s flagship, though this selection would present certain challenges. Because the coffin was too wide to fit through Olympia’s doorways without being turned sideways, it was instead lashed to the deck.

As Lucas Clawson, of the Independence Seaport Museum, noted, the honor guards posted around the casket struggled to avoid being swept overboard when the vessel was bombarded by 30 foot waves resulting from the Tampa Bay Hurricane of 1921 and Tropical Storm #5 off the coast of Florida.

Former Marine Corps and current Air Force historian Kara Newcomer stated that the bulk of the Marines responsible for guarding the unknown soldier on its return voyage had only been in the Corps for a few months. Only Captain Graves B. Erskine and his First Sergeant were themselves veterans of the First World War. One of the pallbearers was also two time Medal of Honor winner and one time Army deserter, Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant Ernest Janson, later a Sergeant Major.

Scott Price, the Chief Historian of the Coast Guard, observed that despite losing a cutter in the Great War, this still-newly established institution had a relatively minimal role in the ceremonial interment of the unknown soldier, being present as official mourners. Members of his service were only granted the right to be buried in National Cemeteries after they became officially recognized as part of the military in 1915.