Fifteen years ago today (March 5, 2005), the USS Nitze (DDG-94) was commissioned. An Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, Nitze has deployed many times in her service history, and was involved in a confrontation with Iranian vessels in August of 2016.

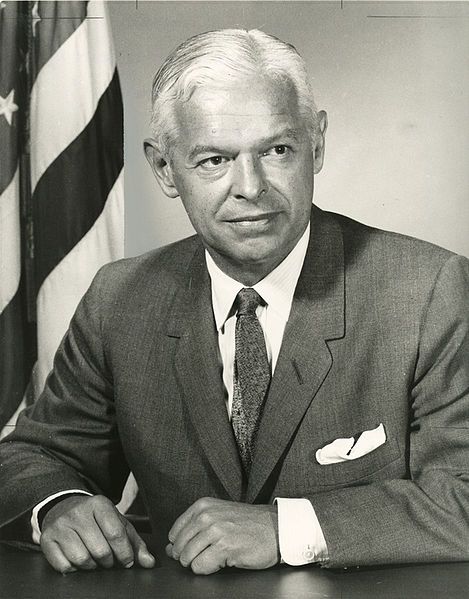

She was named for former Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze – Nitze served in this capacity under President Lyndon Johnson from 1963 to 1967, and for nearly forty years was one of the chief architects of the United States strategy in the Cold War, in addition to serving as Director of Policy Planning at the Department of State and Deputy Secretary of Defense.

A graduate of Harvard College, Nitze entered government service during World War II, and visited Japan shortly after the war’s end to study the damage and impact of the nuclear weapons used there. Following this, he chaired the board that produced NSC 68, a top secret policy paper produced by the Department of State and the Department of Defense that solidified the U.S. policy of rolling back Communist expansion globally during the early Cold War.

Click the JSTOR logo below for a 1984 Naval War College article by Gary Sojka, co-founder of the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, exploring some of the ways Nitze approached foreign affairs and strategy.

One of Nitze’s greatest works on the intersection of moral philosophy and foreign affairs was a 1960 article entitled “The Recovery of Ethics.” In it, Nitze articulated how questions of morality fit into debates about strategy and global politics. The first few paragraphs of this article are reprinted below. The full article can be read as part of the anthology, The Moral Dimensions of American Foreign Policy (Editors Kenneth Thompson and Robert Myers, published in 1984):

One large overarching problem and several smaller subsidiary problems emerge from most discussions of ethics and foreign policy. The big problem is the perennial one of the relation between our convictions about what is right, what is good, what ought to be, and our reading of what we can effectively do in the context of the real situation which confronts us in the world. Everyone faces up to this issue in some manner, but the balance is struck at different points and in different ways by different persons.

At one extreme are those who begin with a more or less absolute, clear and ideal conviction of what is right and good (what God wills or requires) and who insist that it is the church’s and the Christian’s primary duty to preach and to witness to that. To those who take this extreme position, calculations of what is feasible in the real world are largely irrelevant. The focus is on the ideal ends rather than on effective means.

It is important to note, however, that the more ‘idealistic’ positions do not ordinarily assume that the results of single-minded dedication to ideal ends imply any tragic choice between the ideal and the feasible. Rather they tend to read the realities in the light of the ideal, and to assume that a sufficiently imaginative effort to achieve those ideals will meet with success. They do not ordinarily say: witness to these ideals, no matter what comes. Rather, they say: follow these ideas, and the world will be made over. The insistence, for instance, that we need “massive efforts at negotiation and reconciliation, massive efforts at universal disarmament, massive renunciation of efforts contemplating war” surely implies that what is now lacking is sufficient dedication to the ends of reconciliation and peace, and that an analysis of objective conditions influencing the attainment of these aims, and of the alternative courses of action which might in fact lead to a more tolerable and desirable situation, is of secondary importance.

….

How can one best summarize the conclusions that seem to flow from these extreme positions? On the one hand I find unsatisfactory the position of those who would concentrate solely upon ends and principles ordering the use of means. On the other hand, I find equally unsatisfactory the position of those who would look solely to consequences. It appears to me that an adequate approach requires concurrent consideration of ends and principles, on the one hand, and of the consequences which are likely to flow form a given line action in the concrete and specific situation in which the action is proposed, on the other hand. In other words, I do not reject the extreme “idealist” position and the extreme “realist” position in favor of some middle road. Rather, I think that a more elaborate analysis is needed – one involving both a consideration of aims and an assessment of probable consequences.

What do you think? What is your evaluation of Nitze’s approach to an-ethically guided foreign affairs? What effect do you think his position had on world affairs and the history of the United States Navy?

Read an analysis by Mr. Normal Polmar (prolific author and winner of the NHF 2019 Dudley Knox lifetime achievement award in Naval History) of Paul Nitze and the use of atomic bomb:

navyhistory.org/2013/06/normans-corner-paul-nitze-and-the-a-bomb/

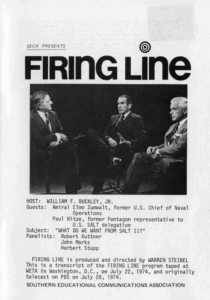

On July 22, 1974, Nitze and former Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, were interviewed by author and commentator William F. Buckley Jr., on his famous show, Firing Line. The three men discussed the second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. Below is the cover for the program, as well as the concluding remarks of discussion.

MR. NITZE: –there I would agree entirely with what Henry Kissinger said in his book, and I’m sure he would today. He would not say that peace is an absolute end. He would say certainly, if one wants to survive as a ‘nation with some degree of sovereignty, one has to face up to the fact that you can imagine circumstances where a nation would fight in its own defense. With respect to the other part of your question, with respect to a status quo nation and its disadvantages, it has not been my impression that the United States really has been a status quo nation. Granted, we have been a status quo nation territorially, we have no territorial ambitions, but I think we have made a most positive contribution toward the world structure, at least in the non-Communist part of the world, during the period from 1946 up until the present.

ADM. ZUMWALT: My answer is that I agree with Paul Nitze.

MR. BUCKLEY: On both of those points?

ADM. ZUMWALT: Right.

MR. BUCKLEY: You have no territorial ambitions?

ADM. ZUMWALT: Right.

MR. BUCKLEY: I don’t know. I’d kind of like to take over Albania. (laughter) Of course, isn’t it true that there is no such thing as a status quo nation almost by definition? There is such a thing as a nation that seeks to freeze history, but there has never been, so far as I know, a nation that has succeeded in doing so, has there?

MR. NITZE: I don’t think so.

MR. BUCKLEY: Certainly not among the superpowers.

ADM. ZUMWALT: I think our mission has been to try to maintain the right of people to free determination as opposed to the Soviet mission, which is to pervert that right into what they call the socialist order.

MR. BUCKLEY: Thank you, Admiral Zumwalt; thank you very much, Mr. Nitze.

MR. NITZE: Thank you, Mr. Buckley.

MR. BUCKLEY: Gentlemen of the panel, thank you all.

You can read the entire interview HERE, or listen to it from the link below.

Pingback: Thursday Tidings – Women’s History Special | NNOA