By MIDN 4/C Alex Hooker, United States Naval Academy

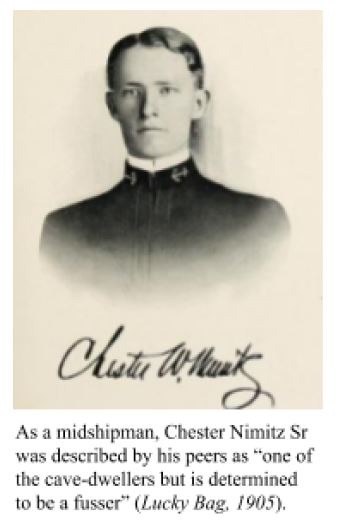

Regarding the possibility of a naval school to train future officers, one salty critic is quoted as saying, “You could no more educate sailors in a shore college than you can teach ducks to swim in a garret.” Considering the long line of brave, consequential officers produced by the United States Naval Academy since opening its doors, it would seem that this “shore college” is doing something right. One-hundred-seventy-five years’ worth of graduates prove annually the value of the Academy as an indispensable resource for the United States. Every year, one thousand young men and women are called from across the country and world to attend this great institution, but only a fortunate few have made service here a family tradition. One of the most famous multigenerational duos is father and son Chester William Nimitz Sr (Class of 1905) and Chester William Nimitz Jr (Class of 1936). Chester Nimitz Sr earned an appointment to the Naval Academy in 1901, although his dream school was West Point. In the 1902 edition of Lucky Bag, the class of 1905 was paid homage with a clever poem called “The Tale of Nineteen-Five” that is applicable to every class of midshipmen:

This is the class of Nineteen-five;

In May its life began;

In June new members swelled its ranks–

Were sworn in man by man.

[…]

So, gentle reader, glancing here,

Forgive this tale of woe.

And feel sincerest sympathy

For the plebes you do not know

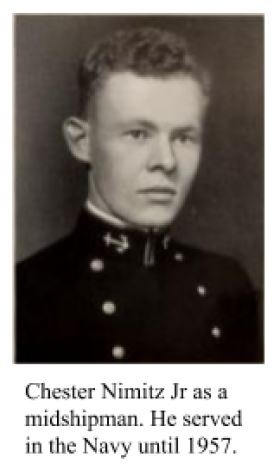

Although it seems difficult to imagine in retrospect, even the Fleet Admiral was once a plebe! Interestingly, Chester Nimitz Sr was at the Academy during the same time as the class of ‘04 midshipman William Halsey Jr who would serve alongside him during WWII and also achieve the rank of Fleet Admiral. Halsey was also the member of a father/son duo; his father, from the class of 1873, even served as the Department of Seamanship head during Halsey Jr’s time at the Academy. Another notable Naval Academy alumnus from the class of 1907, Raymond Spruance, attended during Nimitz Sr’s time, achieving the rank of admiral and becoming the namesake of the Spruance -class destroyers. Chester Nimitz Jr would go on to become a Rear Admiral himself, and while at the Academy, he was described similarly to his father. “Red headed and radical came this conspicuous individual who, born and bred a Navy Junior, was early destined to enter the Academy. […] he is always ready for a nice noisy rough-house,” said one of his peers in the 1936 publication of Lucky Bag , further proving that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree!

Only twenty-seven years passed between the father and son’s time as midshipmen; however, their lives on the Yard were remarkably different. In fact, the early twentieth century saw the Naval Academy evolve constantly. Every alumni of the Academy are forever bonded by their intimate connection with this school, and although many of its deeply-rooted traditions and values seem timeless, each generation of midshipmen has had a measurably different experience. Due to the fast-evolving nature of the Academy during the early 1900s, Chester Nimitz Sr and Jr experienced largely different academics and training, traditions, and lifestyles during their time as midshipmen.

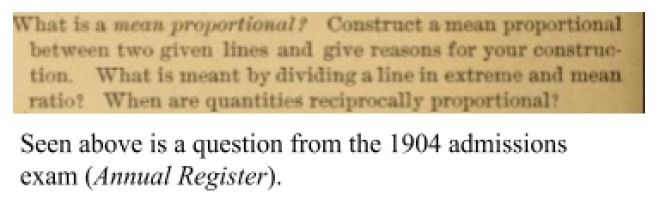

The Naval Academy rapidly improved during the early twentieth century, and two of the most drastically transformed aspects were academics and training. During the time Nimitz Sr went to the Academy, midshipmen were required to complete a four-year course of study followed by two years at sea, during which they were designated “passed midshipmen. In 1912, the policy requiring midshipmen to serve two years at sea was omitted. Fortunately for Nimitz Jr, he never had to serve as a passed midshipman. Along with the changes to the academic courses, students at the Naval Academy have been called a host of different titles to include naval cadet, cadet engineer, cadet midshipman, and acting midshipman; however, both Nimitz men were referred to as midshipmen since they both attended the Academy after Congress approved that title in 1902. Admission into the Academy has also changed over the years. In 1904, midshipmen candidates were required to pass both physical and mental examinations to gain admission. Nowadays, the Academy uses the widely accepted SAT and ACT exam scores.

In 1904, once a midshipman was accepted to the Academy, he immediately signed a contract which bound him to the military for eight years, and during his time as a midshipman, he would be paid five-hundred dollars per year. It is important to note that the majors program at the academy would not be introduced until 1969, so every midshipman within a given class was required to take the same courses. Classes for a 1/C midshipmen at the Academy during Nimitz Sr’s time included seamanship, navigation, ordnance, naval construction, boilers, physics, and a language. In contrast, a class of 1935 1/C midshipman would have taken still taken seamanship, navigation, a language, and ordnance, but instead of boilers, physics, and naval construction, he would have taken gunnery, marine engineering, mathematics, electrical engineering, history, economics, and government. The Academy was moving away from navy-specific technical courses and towards a wider breadth of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) subjects as well as a larger focus pertaining to the liberal arts. Proving that the Academy recognized the importance of graduate education, Secretary of the Navy Curtis Wilbur authorized graduates to compete for the Rhodes Scholarship in 1929, so Nimitz Sr and his classmates never received this opportunity.

Arguably, however, the most impactful change to daily midshipmen academics occurred in 1923 when the Academy established the physical training department. The physical training department required midshipmen to take specialized classes to improve their general fitness and fulfill the Academy’s physical mission. During Nimitz Jr’s time, the 4/C midshipmen were required to be proficient in swimming, strength, gymnastics, posture, boxing, wrestling, and dancing. On 30 October 1930, the Association of American Universities accredited the Academy’s curriculum, and on 25 May 1933, President Roosevelt signed into law an act to provide bachelor degrees for the three major service academies. Luckily, Nimitz Sr and his contemporaries did not miss out because, in 1937, the superintendent was granted the power to award all living graduates with a bachelor of science degree.

During the early days at the Academy, attrition strongly impacted graduation rates. Nimitz Sr’s class of 1905 decreased from 150 to 114 over the course of his four years, down 24%. Comparatively, Nimitz Jr’s class of 1936 decreased from 338 to 262, an attrition rate of 22.5%. This is attributed to many factors, although some are more difficult to quantify. Data from the 1936 Annual Registry of the United States Naval Academy reveal that in Nimitz Jr’s class, forty-nine left due to academic deficiencies, five due to conduct, thirteen due to physical disqualifications, and seven on their own accord. Ten were turned back to the next lower class, one was dropped, two were dismissed, and one poor midshipman completed the scholastic course but was not awarded a diploma. It is no secret that adjusting from civilian life to becoming a midshipman is a difficult task, especially considering the unrelenting harassment of plebes by the upperclassmen.

One plebe from the class of 1935 wrote in a correspondence to his mother, “A first classman has had me writing letters [t]o his girl.” It wasn’t uncommon in the day for upperclassmen to make the plebes do similarly questionable things, some of which assuredly caused plebes to resign. The attrition rate has fluctuated a fair amount over the years, reaching a rather high point of 33% in 1977 during former superintendent VADM Carter’s midshipmen days and a considerably low 14% for the class of 2014. Fortunately, neither Nimitz boy was deterred by mean upperclassmen or the rigorous academic regimine. Between the years of Nimitz Sr and Nimitz Jr, the Academy transformed into a real university, began to place a more rigorous emphasis on physical fitness, and altered the training of midshipmen.

If there is one thing the United States Naval Academy has no shortage of, it is traditions. From the climbing of Herndon at the conclusion of plebe year to the cover toss which occurs at graduation, these memorable occasions are often the most cherished memories which graduates hold onto from their time at the Academy. One tradition, plebe summer, was transformed drastically in 1905 when Chaplain H.H. Clark wrote the first edition of Reef Points. This book, published by the local YMCA at the time, is known colloquially as “The Plebe Bible” and contains hundreds of digestible passages, nonsensical alliteration, historical summaries, and much more. Any midshipman who has passed through the Naval Academy since 1905 has been required to memorize large portions of the book, and its inception changed the training of plebes fundamentally. Now in its 115th edition, Reef Points is an annual tradition which has largely defined plebe summer. Designed to test the plebes in the mental mission of the Academy, Nimitz Sr never had the pleasure of learning “How’s the cow?” or “Why didn’t you say sir?”

The academic year is full of its own traditions; the mere mention of the Army-Navy football game stirs up the adrenaline of midshipmen, parents, alumni, enlisted, and NCAA football junkies alike. The first Army-Navy football game was played in 1890, so both Nimitzs had the pleasure of enjoying this tradition, however, it didn’t become an annual game until 1930, well after Nimitz Sr attended the Academy. In a stroke of good luck, Nimitz Jr watched Navy beat Army during his 1/C year for the first time in 14 years. Customarily, the winning team will join the losing team in singing the losing school’s alma mater. The teams then switch to the winners’ side and sing their school’s alma mater. This act of solidarity is a reminder that, at the end of the day, they are playing for the same team: the Red, White, and Blue. Disappointingly, Nimitz Sr also missed out on the very first singing of Anchors Aweigh at the 1906 Army-Navy football game. Six years later, in 1912, the hat toss tradition began at graduation.

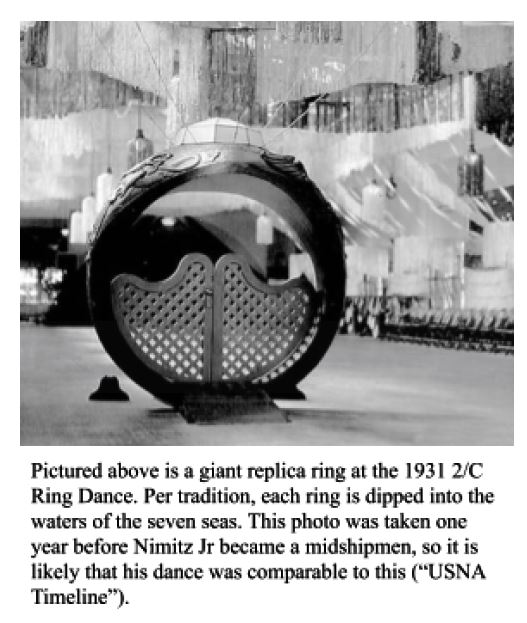

The hat toss has been a staple of graduating seniors since then and is mimicked annually by thousands of other schools across the country. After tossing their midshipmen cover, the newly commissioned Ensigns and Second Lieutenants get to don their freshly minted officer covers, their old ones left on the Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Field to be robbed by a herd of excited children. Tragically, Nimitz Sr never experienced this triumphant culmination of his four years on the shore of the Severn. Another tradition equally as cherished among midshipmen is the 2/C Ring Dance. This formal event for juniors marks the first time midshipmen may wear their class ring. While class rings and class crests have been part of Naval Academy heritage since 186914, the tradition of Ring Dance dates back to 1925, meaning that–once again–Nimitz Sr missed out. One year later, in 1926, “Navy Blue & Gold” by J.W. Crosley was sung for the first time, becoming the school’s alma mater. Hopefully Nimitz Jr taught it to his father! The Academy’s developing campus and emerging clubs meant that Nimitz Sr and Nimitz Jr lived remarkably different lifestyles during their time as midshipmen. During Nimitz Sr’s time at the Academy, the Brigade of Midshipmen expanded from four to eight companies. A change like this signaled that the Academy was prospering and growing. Nimitz Jr and his classmates, who belonged to one of twelve companies, would probably have a difficult time imagining the brigade with only four. The campus grew significantly during the mere four years Nimitz Sr was a midshipman to accommodate the rapidly increasing size of the brigade. For example, he saw the completion of Dahlgren Hall and Macdonough Hall on 7 March 1903 and the placing of the present chapel’s cornerstone by George Dewey on 3 June 1904. These buildings alone define the modern Naval Academy campus.

The year after Nimitz Sr graduated, the Academy completed the first and second wings of Bancroft Hall, and the year after that, they built Mahan Hall, Maury Hall, and Sampson Hall. Mahan Hall housed the library in which all midshipmen were required to spend at least one and a half hours weekly during their first summer. It’s likely Nimitz Sr was glad he never had to endure that requirement! Unfortunately for him and his classmates, however, they graduated two years too early to see the founding of the Masqueraders. The Masqueraders are a group of theatrical performers who bring light to the Academy with their plays and musicals. The Naval Academy Drum & Bugle Corps also was available to Nimitz Jr but not Nimitz Sr. While Nimitz Jr did not partake in either organization, he and his classmates were at least able to march to the rhythmic cadences of the Drum and Bugle Corps at noon meal formations and attend a Masqueraders show on select evenings.

Many more changes to the landscape of the Academy came during the years between which the Nimitzs attended, opening opportunities for Nimitz Jr that did not exist for his father. For example, Nimitz Sr wouldn’t have been able to visit John Paul Jones at his final resting place in the chapel because the body wasn’t moved there until 1913; however, the bandstand across the road from the chapel, constructed in 1922, likely served as an excellent venue from which Nimitz Sr watched his son climb Herndon. Two additional wings were added to Bancroft in 1917 as the modern Academy continued to take shape. Also, Nimitz Jr had the privilege of taking his seamanship and navigation classes in the relatively new Luce Hall, built in 1920. Finally, unlike his father, he was able to experience the Naval Academy natatorium, the largest indoor pool in the country at the time.

Due to the shifting academic focuses, the forming of new traditions, and the quickly expanding Brigade of Midshipmen, Chester Nimitz Sr and Chester Nimitz Jr had many dissimilar experiences during their time here. Notably, however, no change or cluster of changes to the Academy over the years has made it unrecognizable. By-and-large, the Academy is still the same place, and its core values will continue to stand unflinchingly. Midshipmen over the years have more in common than what first meets the eye, and perhaps it is those similarities that should be celebrated. At the end of the day, no amount of class pride can reduce the fact that each graduate has walked the same path, trying not to step on the same seal.

Works Cited:

Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy . Vol. 1904. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904.

Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy . Vol. 1936. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936.

“Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Biography .” The National Museum of the Pacific War. web.archive.org/web/20070424172641/www.nimitz-museum.org/nimitzbio.htm.

Hughes, Thomas Alexander. Admiral Bill Halsey: a Naval Life . Harvard University Press, 2016.

Johnston, John. “John Porter Merrell Johnston Letters.” USNA Digital Collections. February 17, 1933. cdm16099.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16099coll21/id/100/rec/2

Lucky Bag . Vol. 1905. First Class, United States Naval Academy, 1905.

Lucky Bag . Vol. 1936. First Class, United States Naval Academy, 1936.

Prudente, Tim. “Superintendent: Fewer Dropouts Seen at Naval Academy.” Capital Gazette. December 1, 2014. bit.ly/2KDmyUS.

“Ring Dance Tradition.” USNA Class Rings Fan Club. September 13, 2019.

usnaclassrings.com/about/.

“The Army-Navy Game.” www.army.mil. US Army. December 6, 2016. bit.ly/3cRKeRG.

“USNA Timeline.” The U.S. Naval Academy. Accessed April 28, 2020.

www.usna.edu/USNAHistory/History.php.

USNA X3. “USNA 150 Years.” YouTube. www.youtube.com/watch?v=PuTabiMk1jU.