By Michael W. Shelton, Morley, Missouri: Acclaim Press, (2022).

Reviewed by John E. Fahey, Ph.D.

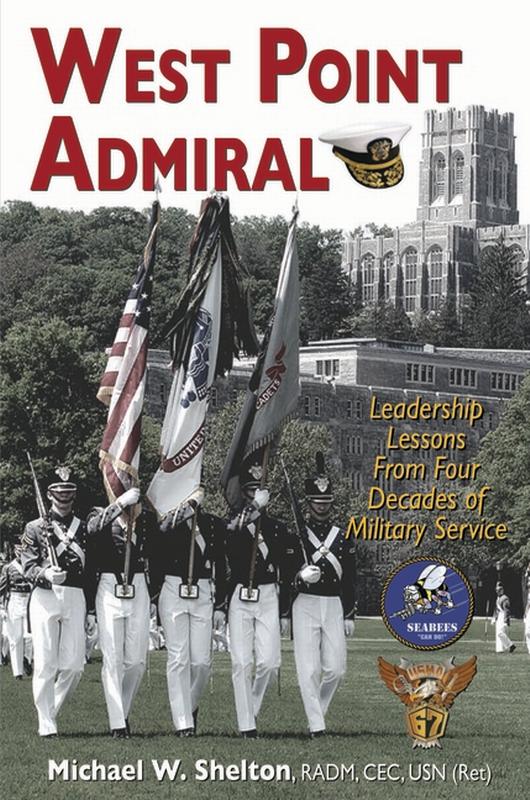

Rear Admiral (ret) Michael W. Shelton took an unusual path to the Navy. In West Point Admiral: Leadership Lessons from Four Decades of Military Service he recounts his time at the United States Military Academy at West Point, and Seabee assignments ranging from Vietnam to the Pentagon. The book grew in part from an essay Shelton wrote for Dan Rice’s West Point Leadership: Profiles of Courage and heavily emphasizes how to develop effective leadership, “based on ethical decision-making, mutual respect, shared risk, and empathy for the troops (10).” His career from West Point Cadet to creator of the Seabee Division is impressive, and his honesty about the strange turns and quirks of the promotion process and Navy careers is a useful look behind the curtain for aspiring officers. The memoir of a successful Seabee officer in the Vietnam and post-Vietnam era, it is also useful as a source on Navy organization and culture in an almost contemporary era.

Shelton grew up in a Navy family, and illustrates the benefit of living in a military family for a military career – his exposure to his dad’s enlisted friends and veterans helped him to relate to enlisted sailors. Despite growing up in the Navy, Shelton ended up at West Point through a chance of grades and luck. His description of his time at the USMA will be interesting reading for Annapolis graduates, as West Point has an unusual culture, which taught him the importance of understanding one’s subordinates and superiors. While at West Point, Shelton was accepted into the Seabees, and was commissioned in the Navy upon graduation. After training, Shelton spent a deployment in Vietnam in charge of communications in a Seabee battalion. The section on Vietnam is one of West Point Admiral’s best, discussing the dangers and hard work of a deployment, and painting a vivid picture of a poorly lead battalion (he describes the commander as a “self-important martinet”), barely held together through the efforts of some of the mid-level leadership and enlisted sailors. At multiple points, Shelton’s enlisted men found ways to accomplish impossible tasks and support him in his job. He also gives good advice about allocating proper troops and protection for the right job, having taken fire when visiting an overexposed construction detachment.

Shelton did two tours in Vietnam, but the bulk of the book is devoted to his rise through the Seabee ranks. He commanded construction units and detachments in Guam, Europe, Japan, and both coasts of the United States and is quite blunt about the challenges of dealing with bad leaders. He portrays himself as something of a traditionalist with regards to command relationships and discipline. Moving beyond command, Shelton is blunt about the process through which officers are selected and promoted, having spent multiple tours on selection and assignment boards at the Pentagon. He credits a great deal of his success to meeting and befriending superiors and peers, enabling him to find the support and help when necessary. He also discusses balancing married life and military responsibilities, a particularly difficult task, since his wife Mary had her own career as a Navy nurse. Shelton finished his career working as CNO Vern Clark’s senior Civil Engineering officer on staff, and was instrumental in creating the Seabee division.

There is much to like about Shelton’s memoir. He uses his personal story to illustrate how to lead effectively and accomplish the mission. Unfortunately, he frequently takes time out of his story to rail against changes to the contemporary Navy. Many of these criticisms are justified, like his theme of critiquing bureaucratic incompetence and the replacement of uniformed military personnel with underqualified Senior Executive Service officers (206ff, 342ff), or misguided selection board policy (330). His frequent critiques of the “sensitivity” and “political correctness” of the Navy don’t hold up as well. He often ends anecdotes with a bitter remark that the former, good way of doing things has been ruined, usually by “lawyers and diversity champions (255).” While this critique can have merit, his examples of bad changes have a tendency to focus on minorities and women, such as when he complains of Native Americans allegedly receiving preferential treatment (299-300), women harassing men (319), or minorities unfairly (in his opinion) placed in positions of responsibility. Some of his suggestions simply do not work in the modern Navy. For example, when discussing military housing, he complains about the military’s “recruiting and retention of single parents,” who demand child care, housing, and health care. Putting aside the fact that most full-time jobs traditionally provide health care, Sheldon attacks the “entitlement mindset” of single parents, calling efforts to support sailors and their families socialist. This attitude is simply not tenable in the United States Navy, as single parents make up almost a quarter of all parents in the USA today. Cutting them off is not an option (340).

At the start of West Point Admiral, Shelton argues that empathy cannot be taught. As he writes, empathy and leadership require “constant feeding through life experiences and exposure to the gamut of personality types of both sexes (22).” This type of exposure, though, requires creating institutions and teams that enable this diversity to thrive, a point that Shelton does not particularly explore. He gives useful advice and examples of leadership, and correctly describes the importance of commitment and discipline from commanders, but struggles to describe sustainable diverse teams, which are an inevitable, and desirable, feature of the United States Navy. All in all, West Point Admiral is a useful memoir, which celebrates the contributions of the Seabees, and illustrates, sometimes unwittingly, the changes that have occurred within the Navy and American society over the last sixty years.

Dr. Fahey taught history at the United States Military Academy and Georgia Military College and currency teaches at George Mason University.

MIKE SHELTON grew up in a Navy family and received a competitive appointment to West Point. He graduated in 1967, was commissioned in the Navy Civil Engineer Corps, serving thirty-four years on active duty, and retired as a Rear Admiral in 2001. He spent the next fourteen years in private industry, first as President of Burns and Roe Services Corporation. He then moved to EMCOR, a multibillion dollar specialty construction corporation, running its government facilities services subsidiary, EMCOR Government Services. He reorganized and expanded it, building annual revenues to over $400 million. He retired as Chairman and CEO in 2015.

West Point Admiral ––Leadership Lessons from Four Decades of Military Service. By USN (Ret) Michael W. Shelton, RADM, CEC (Kentucky, Missouri: 2022).