A Naval Historical Foundation Publication, 1 January 1966

ORIGINAL TEXT OF PAMPHLET

Marine Amphibious Landing in Korea, 1871

Compiled By

Miss Carolyn A. Tyson

Historical branch, G-3 Division

Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps.

This is the fifth in a series or pamphlets covering events of historical interest which the Foundation has published and issued to its members. The previous issues have dealt with subjects related to Naval ships and personnel.

This issue covers an event of significance in the history of the Marine Corps. For its content, the Foundation is indebted to the Corps, and particularly to Miss Carolyn A. Tyson, an Historian in that Division.

It seems appropriate for the Naval Historical Foundation to print this publication as an early example of the proficiency of the Marine Corps in Amphibious operations, and the close cooperation that has always prevailed in such operations.

The letters from Captain Tilton which appear in this pamphlet have been reproduced to be as near their original content as possible. For this reason, the spelling and punctuation have been unchanged.

Foreword

The assault of Marines and sailors on Kangwha Island in 1871 successfully preceded by some 79 years the landing of the 1st Marine Division on Inchon, Korea, just 12 miles to the north. As a tactical operation, the earlier assault was an overwhelming success, despite initial landing difficulties similar to those encountered time and again by Marines in future amphibious operations. The letters of Captain McLane Tilton, USMC, who commanded the Marine detachment, are presented here as a personalized account or the expedition. The Marine Corps appreciates the opportunity to make these letters available though the historical pamphlets of the Foundation.

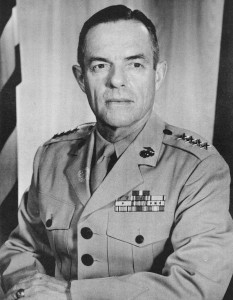

WALLACE M. GREENE, JR.

GENERAL, U.S. MARINE CORPS

COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS

LIEUTENANT COLONEL McLANE TILTON, USMC

Biographical Sketch

Lieutenant Colonel McLane Tilton, USMC, (born Maryland, 25 September 1836; died Annapolis, Maryland, 2 January 1914) was commissioned a second lieutenant on 2 March 1861 and on 1 September 1861 was promoted to first lieutenant. During the Civil War, he served in the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and was on duty at the Marine Barracks, Pensacola, Florida and at the Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. On 10 June 1864, he was promoted to captain, and in the following year he assumed command of the Marine Guard at the Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland. Captain Tilton served as Fleet Marine Officer, Asiatic Squadron from 1870 to 1873, after which time he commanded the Marines stationed at the Navy Yard, Washington, D.C. In 1873 and again in 1883, he returned to Annapolis to command the Marine Guard. He was attached to the USS Trenton and served as Fleet Marine Officer, European Station from 1877 until 1880 when he was again ordered to the Navy Yard, Washington, D.C. to command the Marines there. On 9 March 1888, he was commissioned a major and went to duty at the Marine Barracks, Norfolk, Virginia. He was appointed a lieutenant colonel on 28 February 1891, and, on 1 February 1897, he retired from the Marine Corps.*

*Personnel Department, HQMC Records, Record of McLane Tilton (U.S. Marine Corps Officers Jacket, Records Center Case). Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, Including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1879 (Washington: GPO, 1879), p. 130.]

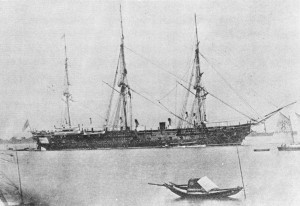

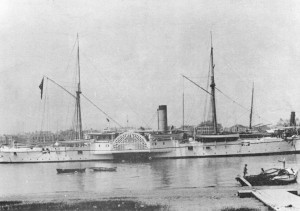

The American Minister to China, Frederick Ferdinand Low, was instructed in 1870 to secure a treaty for the protection of shipwrecked mariners and, should the opportunity seem favorable, to obtain commercial advantages in Korea.[1. Hamilton Fish letter to Frederick F. Low, No. 9, 20 April 1870, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congess with the Annual Message of The President(Washington: GPO, 1870), p. 334.] He sailed from Nagasaki for Boisée Island (Chagyakto) on the Salée (Yom) River in May 1871 on board the USS Colorado,flagship of Rear Admiral John Rodgers then commanding the Asiatic Squadron, The squadron boasted a fleet of nine ships mounting 97 guns; a meager force to guard the lives and property of American citizens over the vast expanse of water and coastline that comprised the Asiatic Station of 1871.

The “Hermit Kingdom” had been under the domination of China for many centuries, refusing intercourse with the world. Her inhabitants were popularly believed in the West to be “far superior to the Chinese in mental and physical resources.” [2. New York Herald, 17 June 1871, p. 7.] A treaty of amity with Korea appeared necessary in view of her central location amidst the trade routes of the East and the brutal treatment accorded foreigners who were shipwrecked off her coast. In 1866, the American ship General Sherman carrying foreign notions for trade with Korea was grounded off the Korean coast and her crew massacred. This event, coupled closely with the expulsion of a French punitive expedition, showed evidence of vigorous anti-foreign sentiment, manifested by tablets erected throughout the country which warned:

“The barbarians from beyond the seas have violated our borders and invaded our land. If we do not fight we must make treaties with them. Those who favor making a treaty sell their country.” [3. E.M. Cable. United States Korean Relations, 1866-1871–English Publication No. 4 (Seoul: Y.M.C.A. Press, 1939), p. 62.]

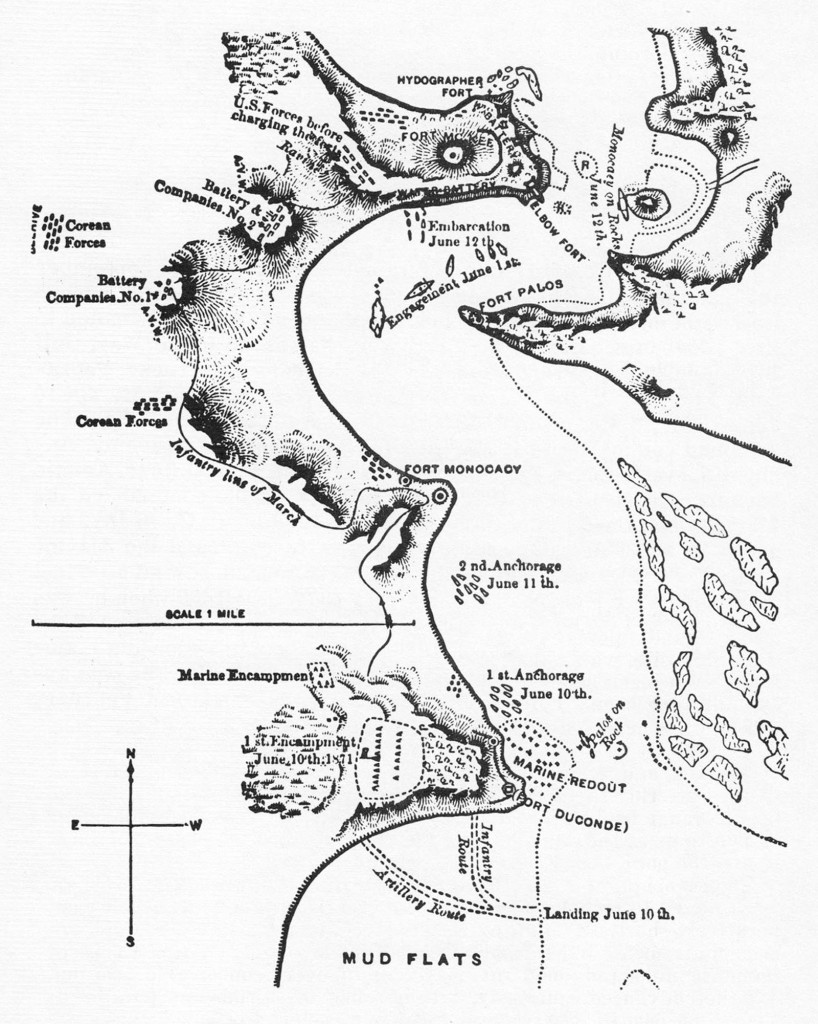

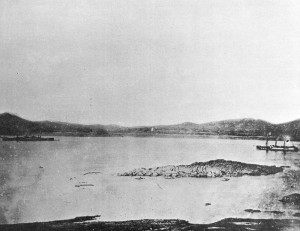

The American expedition first appeared off the coast of Korea on 23 May 1871 at Eugenie Island (Ipp’a-do), also known as Roze Roads for the French admiral who had led the expedition to Korea in 1866. It moved on to a new anchorage near Boisée Island on the 29th where it arrived the following day. From this rendezvous, all operations against the Kangwha forts were directed.

Shortly after the flotilla’ arrival at Boisée, three local officials-diplomats of the 3rd and 5th ranks-visited the Colorado. Minister Low deputized Edward B. Drew, his acting secretary, to conduct an interview with them. Drew informed the Koreans that “only officials of the first rank, who were empowered to conduct negotiations, could be received and to such alone would a full statement of the objects of the expedition be made.” [4. Report of Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 3 June 1871, in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy on the Operations of the Department for the Year 1871 (Wasington: GPO, 1871), hereafter Annual Report…, 1871.] He assured them, however, of the “non-aggressive disposition” [5. Ibid.] of the party and told them that the squadron would take sounding of their waters and make surveys of the shores, to which the Koreans made no apparent objection.

Accordingly, a survey party consisting of the USS Monocacy, Palos, steam launches from the USS Alaska, Benecia, and Colorado, and a steam-cutter from the Colorado was dispatched on the 1st of June. No indication of hostility was evidenced until the party reached the lower end of Kangwha Island where a line of forts, connected by a wall and facing the river, began. At that time, a single shot from the forts initiated a heavy fire from masked batteries as well as the forts along the face of the hill. Despite complications cause by the swift current and jagged rocks, it was promptly returned by all American vessels, and the Korean guns were soon silenced.

Immediately, on the expedition’s return, Admiral Rodgers determined “to equip the available landing force of all ships, and to return in the morning to attack and destroy the fortifications,…[but on consideration,] it was concluded to wait for the next neap tides,” [6. Ibid., p. 277.] when the currents would be less violent than during the spring tides then running. While awaiting the fall of the tides, Admiral Rodgers and Minister Low agreed it would be politic to set a reasonable time for the Korean government to apologize. It was decided that if within 10 days an apology was not forthcoming, an assault would be mounted against the forts.

Ashore, the local authorities, the Intendant Puh and Colonel Ching, immediately dispatched a courier to the King with a report that:

“Two sailing vessels with two masts have suddenly forced their way into Sun-shih Passage. As this is a most important pass leading up into the river, ever since the attack on our troops in 1866, we have increased the guard, and done everything to make it secure: even our own public and private vessels, if they gave no river pass, are not allowed to go through that way. How much less, then, can foreign armed men-of-war, which have not yet apprised us of their intentions, be allowed to go rushing about…The forces stationed in the Pass accordingly opened their guns to prevent them going by.” [7. King of Korea’s letter, enclosure with Rear Admiral John Rodger’s letter No. 6, 7 January 1872, in “Asiatic Station,” vol. 2 (July 1871–November 1872).]

During the established 10-day interval, no apology was offered. So, on 9 June–the eve of the attack–Commander H.C. Blake received orders from Admiral Rodgers “to take and destroy the forts which have fired on our vessels, and to hold them long enough to demonstrate our ability to punish such offenses at pleasure.” [8. Rear Admiral John Rodgers orders to Commander H.C. Blake, 9 June 1871, in Annual Report…, 1871, op. cit., p. 285.] The force detailed totaled 759 Marines and sailors, but the actual number of troops put ashore was 651 men.

Admiral Rodgers recounted in his official report:

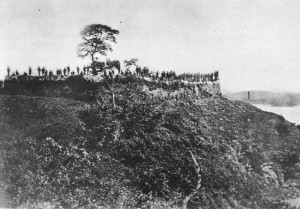

“The point chosen for the disembarkation, while seemingly as good as any in other respects, was, for military reasons, deemed the best, since it flanked the enemy’ works, and left nothing to be feared in our rear. The character of the shore was unknown, and it proved to be most unfavorable for our purpose. Between the water and the firm land a broad belt of soft mud, traversed by deep gullies, had to be passed…As soon as firm ground was attained, the infantry battalion was formed, and the marines deployed as skirmishers. The advance at once began, and the first fort [Ch’o ji jin, named the Marine Redoubt] was quietly occupied…By this time the afternoon was so far gone that it was not expedient to make a further advance on that day. The force, therefore, went into camp upon a favorable spot in the vicinity of the fort.”The marines, with one howitzer, occupied the position in advance of the main body of the force…On the morning of the 11th…the advance began…toward the main objects of attack, the enemy’ forts on the point at the turn of the river, about three miles above.” [9. Report of Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 5 July 1871, Ibid., p. 281.]

The next fort Tokchin, renamed Fort Monocacy in tribute to the accuracy of that gunboat’ batteries, “was found to be entirely deserted…[and] was also dismantled without delay.” [10. Ibid., p. 282.]

The landing force moved on over a terrain of “steep hills, with deep ravines between,…[and] with great fatigue,” [11. Ibid.] toward the main fort Kwangsonchin, called the Citadel but later renamed Fort McKee. The admiral continued:

“Behind the crest of a hill which they occupied our men were formed for the assault upon the citadel, now distant about 150 yards…When all was ready, the order to charge was given by Lieutenant Commander Casey, and our men rushed forward down the slope and up the opposite hill. The enemy maintained their fire with the utmost rapidity until our men got quite up the hill, then, having no time to load, they mounted the parapet and cast stones upon our men below, fighting with the greatest fury.” [12. ibid.]

In the final assault, 243 Koreans and three Americans were killed. Five batteries in all had fallen, and 481 pieces of artillery–ranging from 32-pounders to superannuated gingalls–were destroyed. The following morning, the 12th of June, Commander Blake was ordered to withdraw the party. The fleet remained at Boisée, while notes were fruitlessly exchanged between Minister Low and Korean officials, until 3 July when the Squadron sailed for Cheefoo, China.

Personal impressions of the Fleet Marine Officer, Captain McLane Tilton, as related to his wife Nan (Nannie), appear in the edited letters reproduced below.

No. 12 [13. From the personal papers of Captain McLane Tilton, USMC (Archives and Library, Historical Branch, Headquarters Marine Corpos).]

Off Coast of Japan.

At Sea May 16th 1871.

My dear Nannie

My last letter gave you intelligence of our safe arrival in the beautiful harbor of Nagasaki, and this morning I commence another sheet to let you know we are really on our way to Korea, the fleet sailing & steaming in double echelon the flag ship leading, the “Alaska” & “Monocacy” on our right, & the “Benecia” and little “Palos” on our left, the sky above being as blue as Italy’ own, and the sea as smooth as a lake; the sun shining over all with a warmth that makes us as happy & comfortable as we could wish to be. I hope what you have read in the papers about the Expedition has not alarmed you as I do not think we are to have any trouble to speak of, our mission being a peaceful one, and for the purpose only of exacting a reasonable promise from the Korean Govt. that Christian seaman wrecked on their coast may be treated humanely. We have no knowledge of the country, and only very unreliable information in regard to the coast, as no surveys have yet been satisfactorily made; the only chart being one made of the vicinity of the Capitol, by the French Navy; The navigation will necessarily be somewhat

dangerous but we all trust that by the exercise of great vigilance we will succeed in keeping off of rocks etc. My impression at this moment is, that the people will have no intercourse with us, and our journey will be so much love’s labor lost. However the “denoument” will be fully recorded in this same sheet, if I have the opportunity and I sincerely hope my prophecy will not be fulfilled. The Expedition is known all over the world to be in the topics, and you will doubtless get full accounts by telegraph from California some days before you hear from me. Watch the New York Herald and in the event of our failure you will see much abuse of us, an account of one of their special correspondents not being allowed to accompany the Expedition for some reason best known to our commander in chief. I met the correspondent in Nagasaki just after he received his walking papers. He was just about to return to Yokohama, and was very full of wrath which he will no doubt vent through the columns of the “Herald.” ++ Saturday night, May 20th We arrived yesterday evening at our present anchorage, [14. Ferrieres Islands. Report of Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 3 June 1871, in Annual Report…, 1871 op. cit.,p. 275.] which is about fifty miles from our destination, the high wind preventing us from approaching the land nearer then, and the fog today requiring us to remain as we are, with 360 feet of chain out. We are all quite jolly, and every day the crews of our fleet are exercised in the Infantry drill & firing with small arms. Some months ago a Schooner came up here to trade, and the natives are said to have cut them up, and pickled them, took them in the interior and set them up as curiosities! The French came 3 years ago to avenge their priests, who had been murdered, when they skinned a French doctor, and crucified him on the beach under the eyes of the Frenchmen who had been driven off, and who were unable to help their friends. Whether this is positively true or not I can’t say; but you may imagine it is with not a great pleasure I anticipate landing with the small force we have, against a populous country containing 10,000,000 of savages! My dear Nan will not read the above until our Expedition is at an end, else I am afraid it would scare her. Casey [15. Lieutenant Commander Silas Casey, Jr., attached to the USS Colorado, Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, Including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1872 (Washington: GPO, 1872), p. 20, hereafter Register…, 1872.] has just left my room & as I read it over it does appear rather steep. If it is clear to-morrow no doubt we will get underway and anchor at the mouth of the river if we can manage to get there. I have made a map of Korea and marked our anchorage on it, & will add more as we go on, so that you may understand the situation…Affectionately yours McLane Tilton ++ Sunday noon. My dear Nannie: We approached the shore nearer today but after going twenty miles, the fog compelled us to anchor once more. The weather is very thick, and no land can be seen except now and then a rocky island looming up from out the fog, and looking as inhospitable & cheerless as possible. No one seems to live on them, no vegetation appearing. The tide is very strong; as we came to anchor just now, we spun around like a top. The rise of the tide is nearly 25 feet. With us at home, it is about six feet…times our here are dreadfully dull, & people “busting up” right & left owing to Chinese competition in the Tea and Silk trade.

At Anchor off the West Coast of Korea, May 26th. My dear Nannie, We moved a little nearer our destination since I last wrote and now at anchor in a sort of Bay filled with islands where we will remain until we find out by surveying, which is the most practicable way to get over the next 20 miles, which will bring us to our journey’s end. Probably in a day or two our boats will have finished sounding, and if no obstacle comes in the way, the middle of next week will no doubt find us in communication with the authorities. The islands in our vicinity are inhabited by a few people only, living in thatched huts in the valleys, and all dress in white. They are seen every day clustering on the hill tops, where they squat and I suppose wonder what we are about to do. When our boats are sailing about & meet native boats, the latter always change their course, not appearing to desire any communication; and upon our boats landing on the beach, they get in theirs. [16. The continuation of letter No. 12 is missing from the collection.]

At anchor, near Boisée I’d, Salée River, Korea

4th of June 1871

My dear Nan,

We are still anchored where my last immense letter was finished, and as I have an hour before the steamer leaves for Cheefo, China, (across the Yellow Sea,) will enclose a few more lines, to say we are all as hearty as bucks, and full of having a bang at the Koreans before very long. On June 1st we started our Gunboats “Palos” and “Monocacy”, with four little steam launches, to make soundings higher up the River Salée, and when they reached a mud fort on a point of the River, the Koreans opened on them without a moments warning, when we returned the fire passed the point, and after anchoring shelled the Koreans out; after which the “Monocacy” having struck a rock, which made her leak, the little fleet repassed the fort, and rejoined our Fleet six miles below. The Koreans were not able to fire upon us on our returning, having been cleared out by our big shells. Their guns are very rude, seemed to be lashed to logs, and cannot be trained except on a point beforehand, which, when the vessel nears, they touch them off! The vessels were not struck at all, by large shot, and only by one or two rude balls from a small-arm called “Jing-galls” which two men carry on their shoulders & touch off with a match! Only three of our men were touched, and only slightly wounded; you can judge then how unable they are to cope with us, armed as we are with the latest improvements. The slight damage to the “Monocacy” was repaired before midnight, by allowing her stern to rest on a soft mud bank, the tide receeding lifting her out the water, and the little hole patched as good as new. I was not with the party, but you may be sure we all will be, when we make our next advance up the river, which we probably will very soon, and give them a good drubbing too, for firing upon our little vessels, without giving any warning. Indeed the people we have communicated with, altho’ they did not say they would not fire upon us, should we continue up the River, let us infer they wouldn’t, and we were obliged to return their fire to maintain a dignified position. The little steamer “Palos” goes to night to sea, taking our mail to Chefoo, on Shantung Promontory, in China, right across the Yellow Sea from where we are, about 300 miles, and gets our mail from home, which has been sent there from Yokohama. Today we got a communication from the Head Man at the fort referred to, [17. Published in Papers relating to the Foreign relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congress with the Annual Message of the President (Wasington: GPO, 1871), pp. 130, 131.] who stated that when Capt. Febinger of our Navy came up here, he did not make war on them, and didn’t see why we wanted to come so far to make a treaty. They had been living 4000 years they said, without any treaty with us, and of course they couldn’t see why they shouldn’t continue to live as they do! Now I hope and trust my precious you wont go and get anxious, as we are quite able to do all with safety that the Admiral desires to-do, and the next letter will tell you how we shelled them out and kicked their mud forts down the hill! This is the entire history so far, of the whole matter, but no doubt the papers will be filled with all sorts of stuff and nonsense, as they always are, No communication will be possible with San Francisco for two months after this date, so you can be on your guard for yarns. Our little vessels returned to the fleet after the shelling of the fort, merely to report the circumstances to the commander-in-chief, otherwise they could have demolished it, but the senior officer (Capt, Homer Blake) did not feel authorized to continue the firing, after shelling them out, without communicating with the Admiral in view of our peculiar instructions from the government. Capt. Blake commands the “Alaska” but went up to make the survey…Most affectionately Your husband

McLane Tilton

No. 14

US Ship “Colorado” off Isle Boisée, Corea, Asia

June 21st 1871

My dearest Nannie,

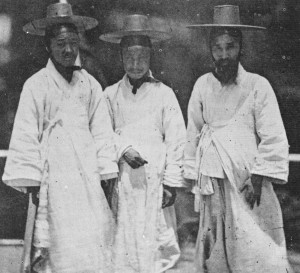

My last letter, No. 13, gave you an account of the firing upon our launches from the Corean forts in the Salée River, whilst engaged in making soundings. I suppose you have all been very anxious about us since, as no doubt the papers have been filled with all sorts of dreadful prophecies in regard to the affair. I am glad to say I am alive still and kicking, although at one time I never expected to see my Wife and baby any more, and if it hadn’t been that the Coreans can’t shoot true, I never should. It is all over now, and as I expected, we have failed to make any treaty with the Coreans. The local authorities near us return all our communications sent on shore to be forwarded to their King, and our Expedition so far as a treaty goes has turned out to be fruitless. We have not force enough to go to their Capital in the interior even if our government directed us to do so. The Country is beautiful; filled with lovely hills & valleys running in every direction and cultivated with grain of all kinds which even now is turning to the colors indicating ripening. Everything is pretty and green, and the little thatched villages are snugly built in little nooks, surrounded by pines & other evergreens. We had a dreadful time on our Expedition, landed six hundred and eighty [18. Rear Admiral John Rodger’s report, 5 July 1871, numbers the landing force at 651 men. In Annual Report…, 1871 op. cit.,p. 280.] in all upon a muddy beach 1/4 mile wide, mud knee deep, but the guns of the Monocacy protected us shelling the first fortification where we landed and drove the Coreans out who retired firing at us, but didn’t hurt anyone. This was Saturday the 10th of June. We all camped that night, the Marines being in advance of the main body about 1/2 or 3/4 a mile. Early Sunday morning we started for the next fort, and took it without any opposition but found the guns in the fort, (brass breech loaders) all loaded, We knocked the ramparts down and proceeded to the great work of the Coreans a redoubtin a neck of land jutting into the river, which formed around it a bent elbow. This place we advanced on and when about 120 yards from it, we laid down on a ridge & blazed away killing about forty in the fort and then we stormed the place which was on a steep hill. The Corean soldiers fought like tigers, having been told by the King if they lost the place the heads of every body on Kang Hoa Island on which the forts stood, should be cut off. Poor Lieut. McKee [19. Lieutenant Hugh W. McKee, USN, attached to the USS Colorado. Register of the Commissioned Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, Including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1871 (Washington, 1871), p. 30.] who was such a beau at the Naval School was killed. He was the first to get over the wall of the redoubt when he was mortally wounded & died six hours afterwards. I and one of my Corporals & one of the Marines of the “Alaska” captured the big yellow flag that flew over the fort. The Alaska Marine was there a second or two before me & my Corporal, but while he was unknotting the halliards, my Corporal & I tore the flag down. It was about 12 feet square with a black chineese character in the centre. Today the Admiral ordered our photograph to be taken with the flag spread behind us, (the Corpl. Private & me), [20. See photograph on p. 15.] so you will no doubt feel glad that your old man gets a little credit without a hole through his skin, which by the by is about the color of a roasted chestnut at this present writing. I wrote a report of what we did during the 10 & 11 of June at direction of the Commanding Officer, [21. Captain Tilton’s report appears here on p. 18.] and send by this mail a copy of it to General Zeilin. [22. Brigadier General Jacob Zeilin, Commandant of the Marine Corps. Register…, 1872, op. cit., p. 122.] If you want to know all about it get Mrs. Z. to have it copied for you. Old Schley [23. Lieutenant Commander Winfield S. Schley attached to the USS Colorado. Ibid., p. 20.] distinguished himself too, and came near extinguishing himself also. But he is as hearty as a buck, and I don’t think any of us will be in any more danger

during the cruise. As for me I am quite satisfied, “I have not lost no Coreans”, and “I ain’t alooking for none neither”- I want to go home! The way the “gingall” or match-lock bullets whizzed was a caution to all those innocents engaged in war. My precious girl I am one of those innocents, and I dont want to engage in any more sick business. We will leave here before long going across to Cheefoo, on the China Coast, from thence to Yokohama so when you get this you may rest assured that none of us are to lose our skins. Your no. 33 & 34 came safely here to me, from Cheefoo, where they had been sent from Japan, Many thanks for them…Affectionately Mc_______….

Off Isle Boisée Corea, Asia,

27th June 1871.

My dear Nan,

My No. 14 I mailed by way of Shanghai per supply steamer “Millet”, and now commence another, which I hope to be able to fill before we reach Yokohama, where we intend going after running across the Yellow Sea to “Cheefoo,

Korean Headquarters Flag captured at Fort McKee by Private Purvis, USMC, assisted by Corporal Brown, USMC, and Captain Tilton (right).

China, where we take Mrs. Low & Flora on board to visit Japan. We are heartily sick of this place no where to take a stroll as the tide as it lowers leaves a wide muddy beach around the islands in our vicinity. I hope this will be the last time I shall use the above heading to my letter, as Corea is as lonesome a place as any we have been to during our cruise. I sent you a photograph of Casey & Me in my No. 14, I hope my letter will reach you in time to assure you that we are all quite well, and none the worse for the fatigue incident to our late Expedition up the river against the Corean forts…By the bye speaking of sights I witnessed some horrible one’ in the Corean forts. Some of them were burnt coal black and dreadfully mangled by 9 inch shells bursting near them. There were forty heaped in a little place not bigger than our quarter deck, most all shot in the head as they looked over the parapet, and their clothes being white the blood was to be seen in more dreadful contrast than usual. They all bled like pigs & it is supposed in about one hour we killed 200 of them. I only saw about fifty killed but strange to say at the time it didn’t affect me more than looking at so many dead hogs. One of our ship’ Quarter-master’ came to me with a pitiful expression and asked me if he should put some of the badly wounded out of their misery by shooting them in the head! I told him of course, such a thing would be murder, and he must let them remain as they were. This seemed to distress him as he thought it would be a kindness to put then out of their misery by shooting them in the head! I merely mention this little circumstance to show how different things seen from different standpoints. The Qr. Master’ motive was kindness doubtless, but surely had he seen anyone injured in a peaceful way, it never would have seemed proper to him to put the sufferer out of his misery by shooting! I enclose a lock of the Corean hair, a large switch of which I got in a village all done up for wear, & perhaps it will be useful for ornamenting the pates of some of our black haired girls at home. It is most too dark for you. The switch is as large as my wrist. A Photographer took views of everything of interest which you will see in the illustrated American & European papers, especially the London illustrated News. I would ask the newsman to save copies should he get the papers containing the ictures, they are worth seeing and give quite a good idea of what is to be seen on the coast of this strange country. I send enclosed also a piece of the large yellow flag which flew over the “Citadel” or fort de Conde, which was captured by the Marines. It had the following character in the centre, meaning generalissimo. The character is Chinese. ![]() The Photographer took a picture of the flag with Private Purvis, Corporal Brown & me, in front of it, who composed the party that hauled the flag down. So if you see a picture in the papers of a very tall couple under arms with blankets across their breasts, and a very small man with his sword drawn & under his left arm, you may know that its me. I had a picture taken which they all here call the “long and the short” of the Marine Guard. The large one is Private Little, and the other is me. I want you to put it on the mantle piece at home as a curiosity from Corea. By the bye I have for you the plume & tassel of peacock feathers & red & yellow horse hair, which was taken from the cap of the General at fort du Conde (of Elbow fort) the best curio of all. I keep quiet about it as they have a nice little way in the cabin of sending down for things of this kind, which like the watermelons I used to watch at home going down the well, I never see again! This between you and me. The weather here is enough to give anyone the horrors. It is raining blowing & fog over everything, and quite uncomfortably close, still we have not yet been obliged to put on linen coats etc. Yokohama is about the only place we havent been yet, and it will be doubly enjoyable coming from this dreary coast, where we have been obliged to coop up in the ships on account of the tides which rise & fall twenty feet and even more when the sun and Moon get in line with the Earth causing spring tides. We are getting our large boats on board and we all hope to sail by the 1st of July, if not sooner…July 3d 2 PM. My dear Nan. Much to our delight nothing prevented us from starting for Cheefoo this morning, altho’ the sky last night was overcast & the weather-wise promised us a fog. We are now on our way to China again, crossing the Yellow Sea, and tomorrow night will bring us to anchor, and Thursday or Friday our letters which have been sent from Yokohama & Shanghai, & from Shanghai will meet us at Cheefoo by another line of steamers. I am, and so are most of us, greatly worried less some brute has started the report at home of a disaster befalling us. The report a week ago at Cheefoo was, that the Coreans had sunk our fleet, and killed and wounded us all except one ship. So strongly was the report credited that a Prussian Man of War, came over to us from there a few days ago to see if they could be of service to us, a very friendly act. They were delighted but surprised to hear of the safety of us, and that we had drubbed the Coreans so thoroughly, I cautioned you in my last letter to place no regard to unofficial rumors appearing in the papers, and hope you have had the good sense to give no weight to reports which you may have seen. Our casualties were very few one officer (Lieut. Mckee) & a sailor & a marine. Several were wounded besides, some 6 or 7 but all are nearly well if not entirely so of their wounds. I mail by this letter a picture of myself and the largest man in our guard whose name is Little. I hope you will receive it…Affectionately McLane Tilton. I have been busy lately on Courts Martial, and also on a board examining small arm ammunition which is very unfortunate for us should another Expedition be necessary. The board was ordered upon a report I made to the Admiral, that I saw great numbers of cartridges in the field which wouldnt go off. I told him 25 per cent was bad. He ordered an examination and we found on one ship that only eight out of a hundred would go off, on another only fifty out of a hundred, and on another only forty out of a hundred were good for anything! We couldn’t go on another expedition if we wished to on this account unless we receive a new supply. Our mission to Corea has been a perfect failure; they wont have anything to do with us not even the fisherman. The local authorities refuse to send our letters to the King, and all are returned to us on the end of a pole stuck up on the beach, where we send a boat for them…Affectionately, McLT

The Photographer took a picture of the flag with Private Purvis, Corporal Brown & me, in front of it, who composed the party that hauled the flag down. So if you see a picture in the papers of a very tall couple under arms with blankets across their breasts, and a very small man with his sword drawn & under his left arm, you may know that its me. I had a picture taken which they all here call the “long and the short” of the Marine Guard. The large one is Private Little, and the other is me. I want you to put it on the mantle piece at home as a curiosity from Corea. By the bye I have for you the plume & tassel of peacock feathers & red & yellow horse hair, which was taken from the cap of the General at fort du Conde (of Elbow fort) the best curio of all. I keep quiet about it as they have a nice little way in the cabin of sending down for things of this kind, which like the watermelons I used to watch at home going down the well, I never see again! This between you and me. The weather here is enough to give anyone the horrors. It is raining blowing & fog over everything, and quite uncomfortably close, still we have not yet been obliged to put on linen coats etc. Yokohama is about the only place we havent been yet, and it will be doubly enjoyable coming from this dreary coast, where we have been obliged to coop up in the ships on account of the tides which rise & fall twenty feet and even more when the sun and Moon get in line with the Earth causing spring tides. We are getting our large boats on board and we all hope to sail by the 1st of July, if not sooner…July 3d 2 PM. My dear Nan. Much to our delight nothing prevented us from starting for Cheefoo this morning, altho’ the sky last night was overcast & the weather-wise promised us a fog. We are now on our way to China again, crossing the Yellow Sea, and tomorrow night will bring us to anchor, and Thursday or Friday our letters which have been sent from Yokohama & Shanghai, & from Shanghai will meet us at Cheefoo by another line of steamers. I am, and so are most of us, greatly worried less some brute has started the report at home of a disaster befalling us. The report a week ago at Cheefoo was, that the Coreans had sunk our fleet, and killed and wounded us all except one ship. So strongly was the report credited that a Prussian Man of War, came over to us from there a few days ago to see if they could be of service to us, a very friendly act. They were delighted but surprised to hear of the safety of us, and that we had drubbed the Coreans so thoroughly, I cautioned you in my last letter to place no regard to unofficial rumors appearing in the papers, and hope you have had the good sense to give no weight to reports which you may have seen. Our casualties were very few one officer (Lieut. Mckee) & a sailor & a marine. Several were wounded besides, some 6 or 7 but all are nearly well if not entirely so of their wounds. I mail by this letter a picture of myself and the largest man in our guard whose name is Little. I hope you will receive it…Affectionately McLane Tilton. I have been busy lately on Courts Martial, and also on a board examining small arm ammunition which is very unfortunate for us should another Expedition be necessary. The board was ordered upon a report I made to the Admiral, that I saw great numbers of cartridges in the field which wouldnt go off. I told him 25 per cent was bad. He ordered an examination and we found on one ship that only eight out of a hundred would go off, on another only fifty out of a hundred, and on another only forty out of a hundred were good for anything! We couldn’t go on another expedition if we wished to on this account unless we receive a new supply. Our mission to Corea has been a perfect failure; they wont have anything to do with us not even the fisherman. The local authorities refuse to send our letters to the King, and all are returned to us on the end of a pole stuck up on the beach, where we send a boat for them…Affectionately, McLT

July 5. 1871. Cheefo, China, My dear Nan. We arrived today and are now at anchor off “Cheefoo”, and at Breakfast regaled ourselves in apricots, the first fruit of any sort we have seen for a very long time. The steamer is expected tonight and I add a line to my already long letter to say we are quite well, and after a week or ten days stay proceed to Yokohama where probably we will be until October or at all events until September…The English & French Admiral have been received on board & our Minister Mr. Low went on shore at 11 o’clock from which time I have been constantly on parade…We are delighted to get away from Corea, and the apricots are splendid. Schley is quite well, but longs to see his wife and babys. He is here now, so is the Alaska. Monocacy & Palos gone to Shanghai…Yours Affectionately Mc…

The report of Captain McLane Tilton, dated June 16, 1871, and the General Order issued on June 5, 1871 by Rear Admiral John Rodgers, Commanding, United States Asiatic Squadron, are printed here as documentary information. They have been reproduced from the “Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy on the Operations of the Department, for the year 1871”. The Secretary of the Navy at that time was The Honorable George M.Robeson.

Report of Captain McLane Tilton, commanding United States Marines.

UNITED STATES FLAG-SHIP COLORADO,

At anchor off Isle Boisée, Corea, June 16, 1871.

SIR: In conformity with your directions, I have the honor to make the following report of the part taken by the marines if the Asiatic fleet in the late expedition against the Coreans:

On Saturday, the 10th instant, the guards of the Colorado, Alaska, and Benicia, numbering one hundred and five, rank and file, and four officers, equipped in light marching order, with one hundred rounds ammunition and two days cooked rations, were embarked from their respective ships and towed up the Salée River by the United Sates ship Palos. Upon nearing the first of a line of fortifications, extending up the river on the Kang-Hoa Island side, the Palos anchored, and by order of the commanding officer all the boats cast off and pulled away for the shore, where we landed on a wide sloping beach, two hundred yards from high-water mark, with the mud over the knees of the tallest men, and crossed by deep sluices filled with softer and still deeper mud. After getting out of the boats a line of skirmishers was extended across the muddy beach, and parallel to a tongue of land jutting through it to the river, fortified on the point by a square redoubt in the right, and a crenulated wall extending a hundred yards to the left, along the river, with fields of grain and a small village immediately in its rear. The fortification had been silenced by the cannonade from the United States ship Monocacy and the steam-launches, and the garrison fled though the brush and fields, firing a few shots as they retired at a distance. The marines, by order, then advanced on the place, sweeping through the grain-fields and village, meeting no opposition, and remained in possession until the main body came up, when we were again ordered to push forward, which we did, scouring the fields as far as practicable from the left of the line of march, the river being on our right, and took commanding a fine view of the beautiful hills and inundated rice-fields immediately around us, and distant about half a mile from the main body. A reconnaissance was then made toward the next fort-a square work of hewn granite foundation, with a split rock, mud, and mortar rampart, crenulated on each face, with a front of about thirty paces-and a messenger dispatched to headquarters with the information that the road was clear and passable for artillery. Pickets were posted on the flanks of our little position, five hundred yards to the right and left–a rice-field inundated being in front–and a Dahlgren 12-pounder planted so as to command the junction of the only two approaches, which the commanding officer had ordered up to us as a support.

An order having been sent to hold our position till morning, we bivouacked with our arms by our sides, dividing our force in three reliefs, one of which was continually on the alert. No incident occurred during the night except rapid firing of small-arms and howling from a hill inland from us, and about a third of a mile distant. Two or three shots from the artillery with the main body were fired across the left of our picket. In the direction of the noise, which presently ceased.

Sunday morning, the 11th of June, the main body came up, and we received orders to push forward, which we did, and after reaching the fields in the rear of the next line of fortifications, we threw a line of skirmishers across the peninsula of hills on which the fort stood, and after the main body came up we advanced toward the rear face, with two-thirds of our guards in reserve. We entered this second place, after reconnoitering it, without opposition, and dismantled the battlements by throwing over the fifty or sixty insignificant breech-loading brass cannon, all being loaded, and tore down the ramparts on the front and right face of the work to the level of the tread of the banquette.

The ramparts consisted of a pierced wall of chipped granite, with a filling of earth in the interstices and coated over with mortar, giving it the appearance of being more solid than it really was. The cannon were rolled over the cliff into the water by Bugler English, without much trouble, who climbed down for this purpose. I cannot give the weight, but the bore was not over two inches diameter. A photographer came on shore from the Monocacy and succeeded in taking a negative picture of the place. We were then ordered by the commanding officer to push forward and find the road leading to our objective point, and to cover the flanks of the main body, which we did with two-thirds of the marines deployed, the remainder in reserve.

We scoured the scrubby woods and fields of grain, stirring up two or three unarmed native refugees from the village we had just passed, who were not, however, molested; and, after progressing half a mile, down deep ravines and the steepest sort of hills, were fired upon from a high ridge a little to the left of us, up which our skirmish line cautiously wheeled, and upon reaching the summit saw the enemy on a parallel ridge opposite, who blazed away at us with their gingalls or matchlocks, their black heads popping up and down the while from the grass, but only one spent bullet struck us, without any injury. A piece of artillery was here brought up from the valley beneath us, by direction of Lieutenant Commander Cassel, by superhuman exertions on the part of his men, and several shells landed among the enemy grouped on a narrow range leading to the circular redoubt-our objective point, and known to us as the citadel, being the third work of the line of fortifications – the main body following in column of fours.

Upon reaching a point a third of a mile from this work, a general halt was ordered to rest the men, who were greatly fatigued after their comparatively short, although extremely steep, march; the topography of the country being indescribable, resembling a sort of “chopped sea,” of immense hills and deep ravines lying in every conceivable position. We then advanced cautiously, with our line of skirmishers parallel to the right face of the redoubt, which was our point of attack, concealed from view from the enemy, and took position along the crest of a hill one hundred and fifty yards from him, closing intervals to one pace on the right skirmisher; the line extending along the ridge, our right resting in a path leading to the redoubt, upon which planted about twenty-five banners in single file, a few feet apart, and at right angles to our line, the first banner being only four paces from our right skirmisher. Thirty paces in front of us was another ridge, parallel to the one we now occupy, but in order to reach it the whole line would be exposed to view. The main body came up and formed close behind us. The banners seemed to be a decoy, and several of us went from our right, took about fifteen of them, which drew a tremendous hail of bullets from the redoubt, which relaxed in half a minute, when away we pushed, availing ourselves of the opportunity to get to the next ridge, accomplishing the move with the loss of only one man, a marine from the United States ship Alaska,although for several seconds exposed to a galling fire, which recommenced immediately after the rush began. Our lines were now only one hundred and twenty yards from the redoubt, but the abrupt slope of the hill and weeds covered us very well. The firing now commenced rapidly from both sides; ours increasing as the men got settled comfortably, and their fire was effective, as the forty or fifty killed and wounded inside the redoubts show. The firing continued for only a few minutes, say four, amidst the melancholy songs of the enemy, their bearing being courageous in the extreme, and they exposed themselves as far as the waist above the parapet fearlessly; and as little parties of our forces advanced closer and closed down the deep ravine between us, some of them mounted the parapet and threw stones, &c., at us, uttering the while exclamations seemingly of defiance. One of these little parties, the very first to enter the redoubt, was led by our beloved messmate, the noble, the brave, the heroic McKee, who fell pierced with a bullet in a hand-to-hand struggle on the ramparts.

The yellow cotton flag, about 12 feet square, with a large Chinese character in black on the center, thus: ![]() , which flew over the fort, was captured by the marines. It was torn down by Corporal Brown, of the Colorado’ guard, by my direction, while Private Purvis, of the Alaska’s guard, was loosing the halliards at the foot of the very short flag-staff. Private Purvis, of the Alaska’s guard, had his hand on the halliards a second or two before any one else, and deserves the credit of the capture.

, which flew over the fort, was captured by the marines. It was torn down by Corporal Brown, of the Colorado’ guard, by my direction, while Private Purvis, of the Alaska’s guard, was loosing the halliards at the foot of the very short flag-staff. Private Purvis, of the Alaska’s guard, had his hand on the halliards a second or two before any one else, and deserves the credit of the capture.

Corporal Brown deserves equally with him to be honorably mentioned for his coolness and courage. The command, to a man, acted in a very creditable manner, and all deserve equal mention. The officers of the marines were Lieutenants Breese, Mullany, and McDonald, who were always to found in the front.

The wounded were soon attended to by the surgeon’ corps, who removed them to the Monocacy, lying in the stream. The place was occupied all Sunday night, the artillery being posted on the heights, and commanding the rear approaches, the men bivouacking with their companies on the hills. Early Monday morning the entire force re-embarked on board the Monocacy, the marines being the last to leave.

The re-embarkation was accomplished in a masterly manner, in the space of an hour, no confusion whatever occurring, although the current was very strong, the rise of the tide being nearly 20 feet. The Monocacy then steamed to the fleet, some ten miles below, where we all rejoined our respective ships.

Of the marines there was one killed, and one severely wounded; the first being Private Dennis Henrahan, of the Benicia’s guard, and the wounded man Private Michael Owens, of the Colorado’s guard, shot through the groin as he was charging toward the redoubt, falling about forty paces from the parapet. The accouterments and arms of the guard of this ship were returned, and no loss of property occurred. The expenditure of ammunition was sixteen hundred cartridges, about forty rounds each man.

I trust it will not be considered out of place in this connection to mention that I picked up from the field great numbers of copper-shell cartridges, unexploded, although the shell bore evidence of having been well struck by the firing-pins. Upon filling the heads of some of these shells, so as to expose the tinned cup holding the fulminate, I found the appearance of oxidation around the cavity holding the fulminate, and on the inside of several cases I found the tinned surface of the cup entirely gone, and one-sixteenth of an inch of what looked like the rust of iron filling the bottom of the cup. Upon inquiry I found the men complained of the cartridges packed in paper boxes, while no complaint was heard from them who had been furnished with cartridges in wooden boxes.

From the great number of unexploded cartridges I saw on the field, although having a deep indentation in their heads from the pins, I am led to think that it will be dangerous to trust to any of the cartridges in the fleet, packed in paper boxes, and marked “Frankfort arsenal, 1869,” and I believe that at least 25 per cent. of them are utterly worthless.

I would respectfully suggest that this fixed ammunition be thoroughly tested, and the good separated from the worthless. For curiosity I today got an unopened box of each kind, and, with a Remington carbine, fired them with the following result. Not a single cartridge packed in the wooden box failed to explode, and not one required to be struck the second time. Fifty per cent. of those packed in the paper boxes failed altogether, and several of those that did explode required to be struck twice, and, in two instances, even three blows were struck before explosion, showing that the sensitiveness of the fulminate had materially deteriorated, probably by some galvanic action; at all events, it was bad. One rifle carbine was shown me which seemed to have a weak mainspring, as it worked stiffly and failed to explode a cartridge.

I examined the arm and found the apparent weakness of the spring to be owing to the gummed oil on the large pin upon which the hammer revolves; the stiffness thus occasioned over so great a surface prevented the hammers from operation with sufficient force, the strength of the spring being too much spent in overcoming the friction occasioned by the gum. Upon removing the pin, wiping and putting it back in its place, a matter of a few moments, the piece worked perfectly.

One carbine burst about three inches from the muzzle, but it was evidently not caused by improper welding, as the fracture presented an irregular surface. The barrel of the gun on the outside looked as if it had been pushed into stiff mud, and probably a long wad of mud was inside the barrel when the rupture occurred.

Very respectfully, yours,

McLANE TILTON,

Captain U.S. Marine Corps,

And Fleet Marine Officer, Asiatic Fleet.

[General Order.]

UNITED STATES STEAMER BENICIA,

Boisée Island, Corea, June 5, 1871.

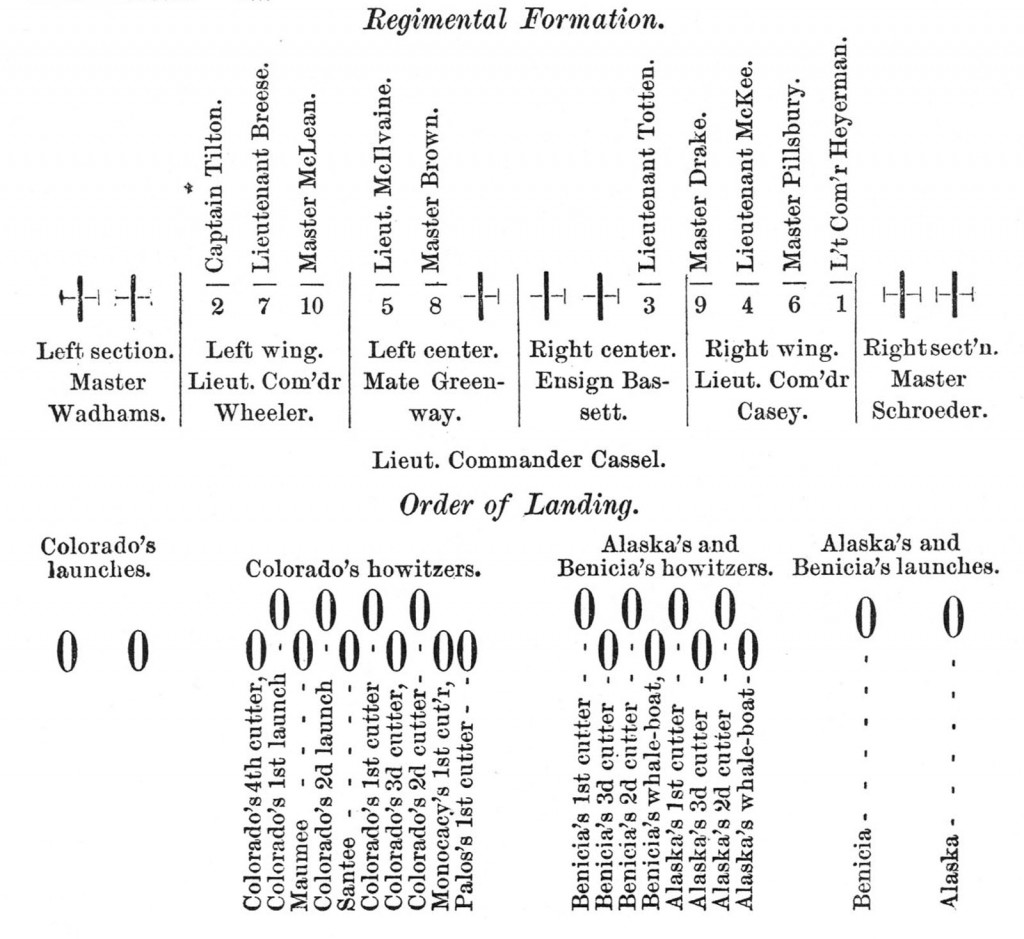

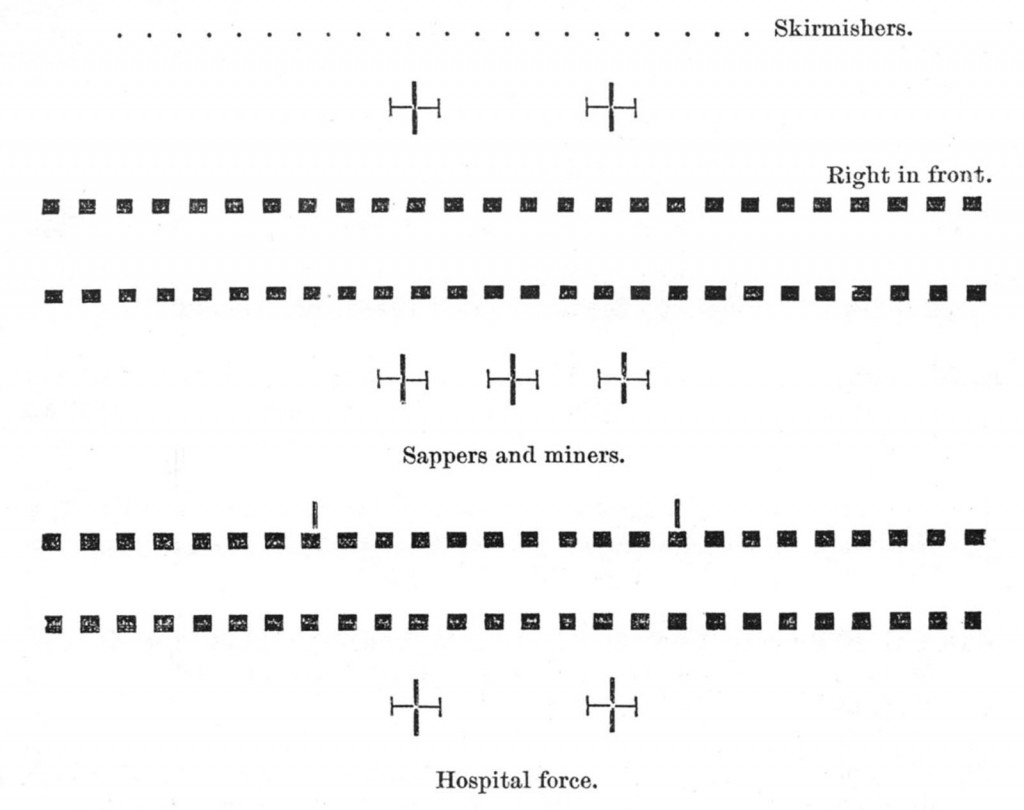

For the information of all officers, the following organization and arrangement of forces will prevail in the expedition against the Corean fortifications:

Signal officer, Mr. Houston; Commander L.A. Kimberly, commanding land forces; Lieutenant Commander W. Scott Schley, adjutant general; Mate A.K. Bayler, aid.

Infantry.–Lieutenant Commander Casey, commanding; Lieutenant Commander Wheeler, second in command; Company A, Lieutenant Commander Heyerman, Ensign Clarke; Company B, Master Drake; Company C, Lieutenant Totten; Company D, Lieutenant McKee; Company E, Lieutenant McIlvaine; Company F, Master Pillsbury; Company G, Master McLean; Company H, Matser Brown and Mate Callender; Company I, Captain Tilton, Lieutenant McDonald; Company J, Lieutenants Breese and Mullany.

Artillery.–Lieutenant Commander Cassel, commanding; Lieutenant Snow, right battery; Lieutenant Mead, left battery; Master Schroeder, right section; Master Wadhams, left section; Ensign Bassett, right center section; Mate Greenway, left center section.

Pioneers.–Mate Quin, commanding; 20 men from Colorado; 8 men from Alaska; 8 men from Benicia.

Hospital force.–Passed Assistant Surgeon Wells and Assistant Surgeons Latta and Corwin; 6 men from Colorado; 3 men from Alaska; 3 men from Benicia.

The launches and boats with howitzers will land two boat lengths apart.

The second line of boats will land to the right, except Colorado’s fourth cutter, which will land to the left of the launch on her immediate right.

On landing the infantry officer commanding will throw out skirmishers to clear away opposition. The artillery will then land and proceed to form in rear and follow after infantry until a sufficient space is obtained to form in the regimental formation above prescribed. The order of march will be in column of fours, unless a sufficiently clear space will admit of company front, viz:

Artillery to be armed with cutlass and pistol.

Sappers and miners armed with pistols.

Hospital force armed with pistols.

Thirty rounds of shrapnel, 10 rounds of shell, and 10 canister to each gun will be carried in the boats.

Fifty additional rounds, in the same proportion to each gun, will be sent to Monocacy and Palos, 60 rounds of ammunition, for small arms, will be carried by each of the infantry, 100 additional rounds will be sent on the Monocacy and Palos.

Sappers and miners will carry intrenching tools.

Each man will carry his blanket, made up in a roll, over shoulder, and his pot slung to his belt. Men will be provided with two days’ cooked rations.

The order of landing is to prevent confusion, and should the current derange the plan proposed, the boats will land as nearly as circumstances will admit in the order prescribed.

After the landing party are on shore the pulling boats will be hauled off and anchored in the most safe and convenient place for re-embarking the force, if it should be necessary.

By order of the commanding officer.

W. SCOTT SCHLEY,

Lieutenant Commander, United States Navy, Adjutant General.

Approved June 8, 1871.

JOHN RODGERS,

Rear-Admiral, Commanding United States Asiatic Squadron.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

E.M. Cable. United States Korean Relations, 1866-1871–English Publication No. 4, Literary Department of the Chosen Christian College, Seoul: Y.M.C.A. Press, 1939. 229 pp.

Rear Admiral John Rodgers. “Asiatic Station,” vols. I & II. The National Archives, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Records (Record Group 127, entry 80 (1869-1874)).

Major C.F. Runyan, USMC. “Captain McLane Tilton and the Korean Incident of 1871,” pt. I. Marine Corps Gazette, v. 42, no. 2 (Feb. 1958), pp. 36-48. Illus.

__________________. “Captain McLand Tilton and the Korean Incident of 1871,” pt. II. Marine Corps Gazette, v. 42, no. 3 (Mar 1958), pp. 36-50. Illus., maps.

U.S. Department of the Navy. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy on the Operations of the Department for the Year 1871. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1871. pp. 12, 13, 275-313.

U.S. Department of State. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congress with the Annual Message of the President, 5 December 1870. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870. pp. 331-339.

_____________________. Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congress with the Annual Message of the President, 4 December 1871. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1871. pp. 275-313.

FOOTNOTES: