Published by the Navy Museum Foundation, a project of the Naval Historical Foundation, Washington Navy Yard, DC, 2002

ORIGINAL TEXT OF PAMPHLET

FOREWORD TO THE 1983 MONOGRAPH

It is particularly appropriate that this exhibit was made possible by the generosity of the late Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, USNR, who donated the royalties from his definitive History of United States Naval Operations in World War II to the Naval Historical Center.

When we think of Admiral Morison, this splendid series comes quickly to mind. He is also prominently associated with the history of the early discovery and exploration of the Americas. Yet, Samuel Morison’s interests were as far-ranging as his knowledge was profound. In a long list of splendid books and articles, he discussed sources, events, and personalities of our early history with wit and acumen. His biographies of John Paul Jones and Matthew Calbraith Perry demonstrate a deep understanding of, and appreciation for, the struggles and sacrifices of America’s first generations. It is my hope that this exhibit will, in its own way, serve the same purpose.

JOHN D. H. KANE, JR.

Rear Admiral, U.S.N. (Ret.)

Director of Naval History

FOREWORD TO THE 2002 MONOGRAPH

Rear Admiral Kane’s hopes for the gun deck exhibit clearly have been fulfilled. Since the gun deck exhibit was installed at the Navy Museum two decades ago, thousands of school children and other museum visitors have sat down on the wooden deck to hear Navy Museum docents describe the roles of gun captains, spongers, rammers, and powder monkeys. These young Americans certainly have a greater appreciation for the struggles and sacrifices made by their forebears who served their young republic at sea. Meanwhile under the stewardship of the Naval Historical Center, the USS CONSTITUTION has entered its third century as the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat. Indeed, the famed frigate celebrated her 200th birthday in 1997 under sail in Massachusetts Bay.

The Navy Museum Foundation is pleased to reprint this original 1983 Naval Historical Center publication for sale in the Navy Museum Gift Shop. It is noteworthy that the author of this short monograph, John Reilly, has retired from the Naval Historical Center and now works for the Foundation as a researcher-writer.

Through the purchase of this publication you are helping to support the Navy Museum and we are most grateful. More information about our organization and how you can help is located on the inside of the back cover.

William L. Ball, III

Chairman

Navy Museum Foundation

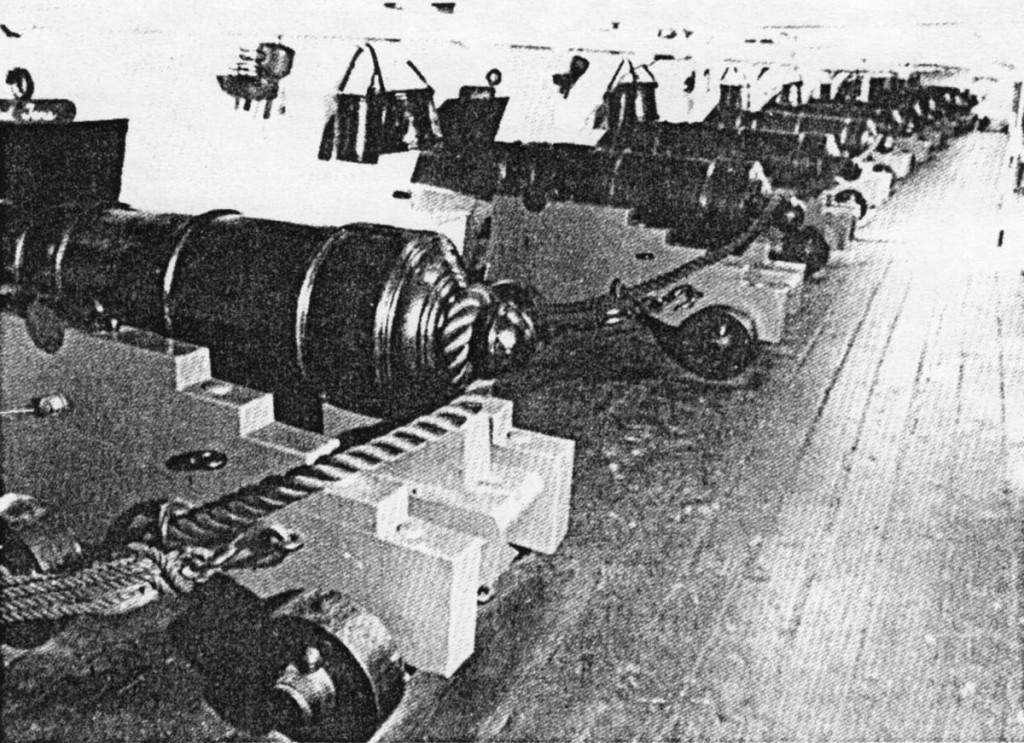

CONSTITUTION’s spar-deck battery included “chase guns” as well as these short-barreled 32-pounder carronades.

The Constitution Gun Deck

By John C. Reilly, Jr.

From the early years of our country’s history, the frigate Constitution has been one of the symbols of our national identity. Conceived during the presidency of George Washington, she protected American merchant seamen in the Quasi-War with France and projected American sea power into the Mediterranean during the Barbary Wars. In the War of 1812, she earned glory in a series of victorious combats with British men-of-war and became part of the American legend. Joshua Humphreys helped to design her; such men as Edward Preble, John Rodgers, Isaac Hull, William Bainbridge, Thomas Macdonough, and George Dewey have commanded her. When she was threatened by the scrapper in 1830, Oliver Wendell Holmes’ poem Old Ironsides awoke national feeling and helped to save her. Still in commission as a ship of the United States Navy, she flies the fifteen-star flag of 1812 at her berth in the old Boston Navy Yard and reminds each new generation of Americans of the vital role the sea has always played in our people’s history.

Five years ago, after Constitution had been overhauled, one of her former fighting tops was brought to the Navy Memorial Museum and installed on a replica of part of her foremast. This has aroused much interest in Constitution and in her history among visitors to the museum. To bring her a little closer to our visitors, we have created a replica of part of Constitution‘s gun deck on the museum floor near the fighting top. To those who have visited Constitution, may this facsimile serve as a vivid reminder of this great ship. To those who have never seen her, we hope that this display may give something of an idea of the tools with which the seamen of our formative years won and defended America’s existence as a nation.

We are accustomed to measuring the strength of a navy in terms of many different types of ships and weapons. The seagoing fleets of 1812 were all made up of wooden sailing ships which might differ in size and function but were all, basically, “sisters under the skin.” They dealt in one weapon, the gun, and it was in terms of guns that a warship’s size and power were measured. The bigger a ship, the more guns she could carry and, of equal importance, the heavier the guns she could use. Where a small ship might be armed with 6-pounders (guns which threw a 6-pound shot), a large ship-of-the-line, the battleship of her day, mounted guns firing shot of as much as 32 pounds in weight. Constitution falls into the upper middle of this spectrum of warship size. For her time, she was the equivalent of a large modern cruiser, armed with heavy ordnance.

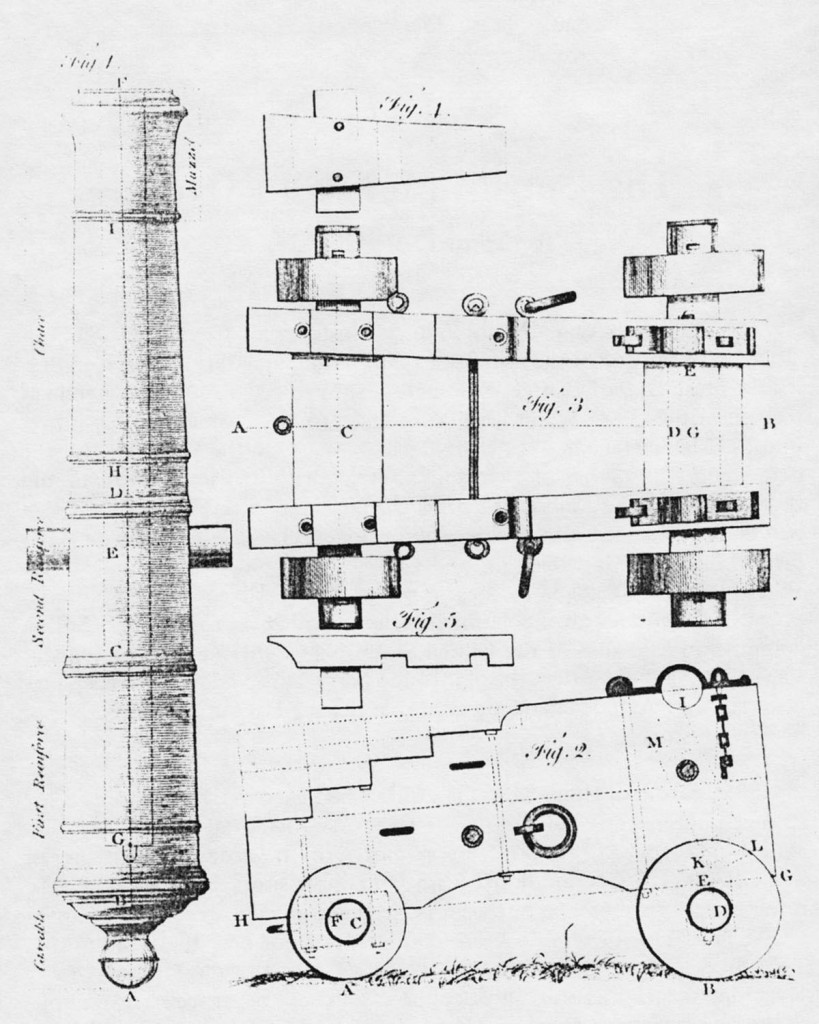

An eighteenth-century drawing of a typical naval gun and its truck carriage. Weapons of this type were a mainstay of naval warfare from the introduction of gunpowder until well into the nineteenth century.

Constitution’s spar deck, her open “weather deck,” was usually the busiest part of the ship. On a portion of it astern called the quarterdeck, the officer of the deck and the helmsman stood their watches. From here the captain — and the commodore, when Constitution served as flagship of a squadron—The rest of directed their commands. The spar deck was also the frigate’s “engine room.” Above it rose the massive network of masts and rigging which propelled Constitution through the water. This was often a hive of activity as the hands double-timed to their stations to make or to take in sail or to man the web of lines that adjusted the spars to take advantage of the wind. Part of Constitution’s armament was mounted here; 22 32-pounder carronades were behind broadside ports (the openings seen in the upper portion of this display), while three bow-chaser guns were carried on the forecastle.

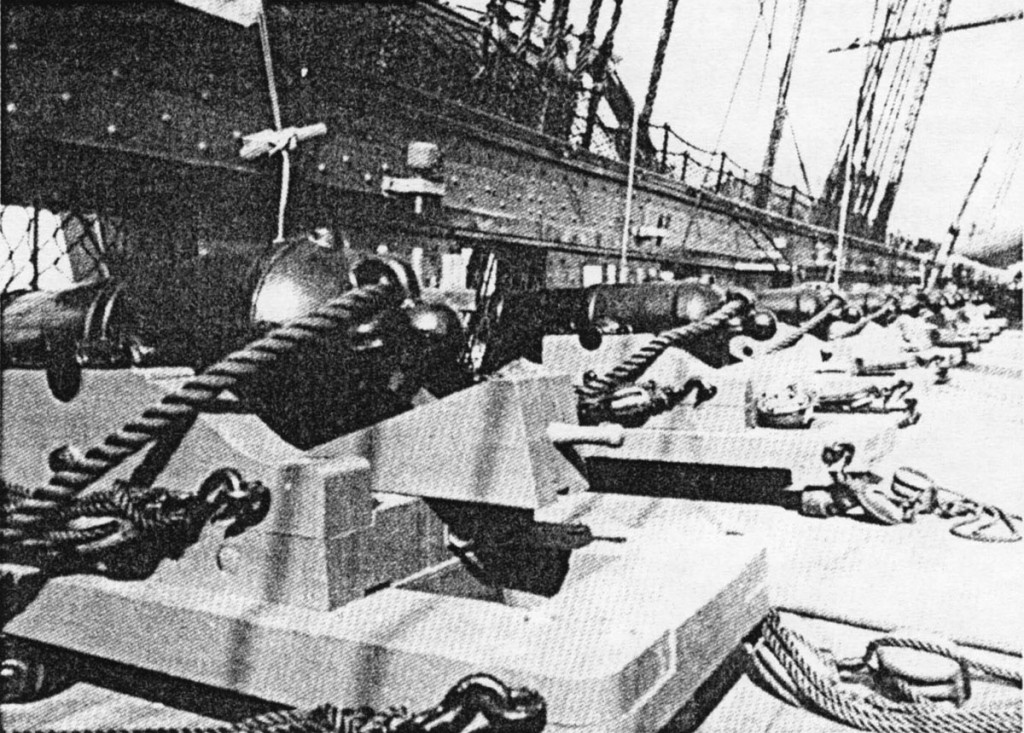

Constitution’s punch was provided by thirty cast-iron 24-pounder guns installed on her gun deck, 15 to each side. These were organized into five-gun divisions, each commanded by a lieutenant. Two replicas of these guns, with their carriages and the assorted implements used in serving them, are at the heart of this display. For its day, the 24-pounder was a powerful weapon. Nine and one-half feet long from breech to muzzle, with a 5.8-inch bore, with its carriage it weighed nearly three tons. Like all the artillery pieces of its day, it was a black-powder smoothbore firing a round iron shot. Dismantling shot, a generic term for different types of special shot used to tear up an opponent’s sails and rigging, included bar shot—two ball halves connected by an iron bar—and chain shot, an iron ring to which several lengths of chain were fastened. Chain shot was sometimes called star shot from the way the sections of chain opened up, star-fashion, in flight. Another form of chain shot consisted of two round shot connected by a short chain. Grape and canister, containers of large and small “scatter shot,” were used at close range against an enemy’s crew. The gun was mounted on a simple wooden carriage which was controlled by an arrangement of lines and tackle. The tools used to load and fire the gun were stowed on the bulwarks. Nearby shot racks held the iron “cannon balls” that were the naval gun’s principal stock in trade.

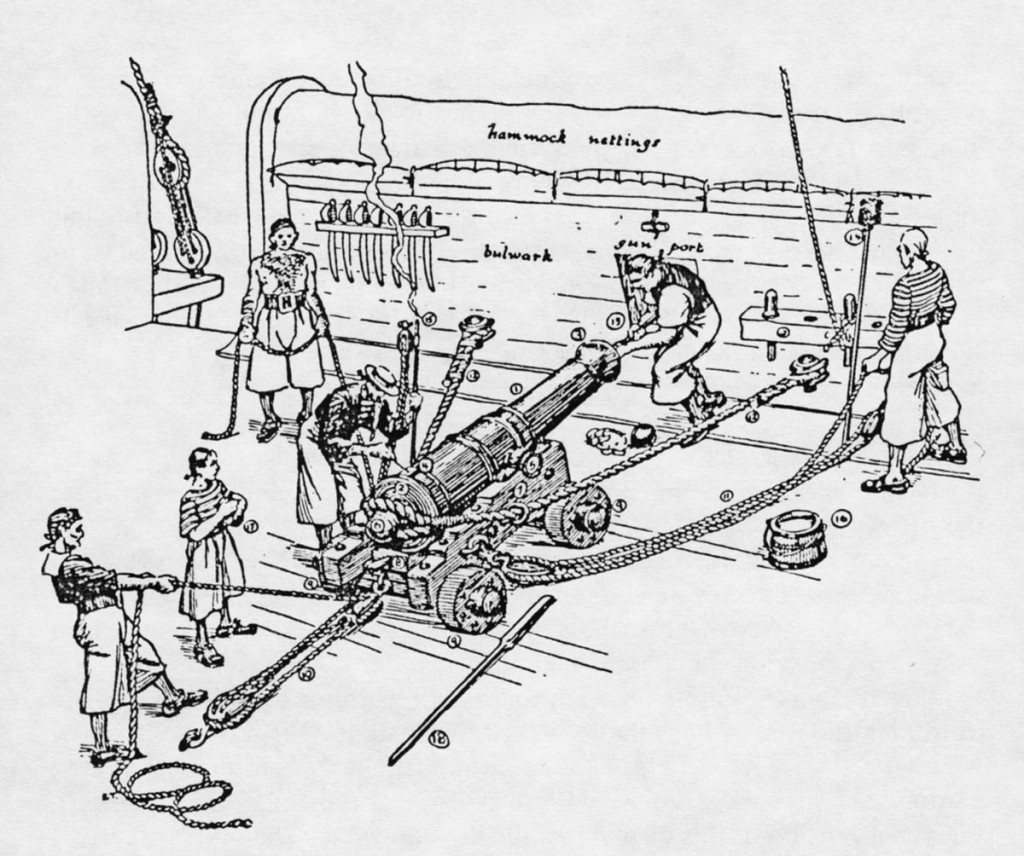

A 24-pounder gun in the period of the Revolution and the War of 1812. The gun is in its recoil position for loading, and the man to the left is keeping a strain on the train tackle to hold the ponderous weapon in place while the man at the muzzle rams the load home. The man at the breech is piercing the powder cartridge with a priming wire before inserting the priming tube: in his left hand is a linstock, a wooden staff holding a piece of burning slowmatch. When the gun is ready to fire, the two side tackles will be used to run it out. The numbers in the drawing identify parts of the gun and its outfit.

|

1 |

Barrel |

7 |

Carriage |

13 |

Rammer | ||

|

2 |

Breech |

8 |

Quoin |

14 |

Sponge | ||

|

3 |

Muzzle |

9 |

Truck |

15 |

Linstock with Slowmatch | ||

|

4 |

Vent |

10 |

Train Tackle |

16 |

Water Bucket | ||

|

5 |

Trunnion |

11 |

Side Tackle |

17 |

Powder Box | ||

|

6 |

Cascabel Knob |

12 |

Breeching |

18 |

Handspike |

When an enemy was in sight, the crew was called to quarters, as “battle stations” were then called. Since there were no loudspeakers in those days, the ship’s marine drummer summoned the men to their stations. In a quick scramble of disciplined activity, everything not needed for battle was struck belowdecks. The galley fire was put out; furniture in the captain’s and commodore’s cabins was moved belowdecks to make room for the gun crews. A detail of men mounted each of the ship’s fighting tops to make emergency repairs to battle-damaged rigging. Down below, the surgeon and his mates laid out their bandages and instruments and made ready to care for the wounded. Sand was scattered along the decks for better footing; tubs were filled with water for drinking and firefighting.

On the spar deck and gun deck, most of the ship’s company busied themselves getting her armament ready for use. Each of the gun-deck 24-pounders had its assigned crew of a midshipman and 13 men. This was an unusual arrangement; midshipmen were more usually assigned to duty as assistant division officers or posted on the quarterdeck to relay the captain’s orders in the din of battle. In 1812, however, Captain Bainbridge had twenty midshipmen on his strength, and decided to assign most of his young prospective officers to the big guns. Fourteen of Constitution’s 15 gundeck 24-pounder crews were commanded by midshipmen; the 15th was in charge of the captain’s clerk, who was apparently a versatile individual.

The gun crew first unfastened the lashings which held the gun secure at sea. This had to be done with care. Gun carriages were not fixed to the deck; if one should break loose in a seaway, the consequences could be dangerous to the ship and fatal to the men who had to bring the massive rolling weight under control. To this day, a dangerously-irresponsible individual is sometimes called a “loose cannon.”

The crew now removed the covers that kept dampness out of the bore, and took various gunnery implements from their racks. Guns of this period were equipped with firing locks, but lengths of lighted slow match-cord soaked in an inflammable solution; it burned down slowly, as a lighted cigarette does-were put in safe places along the gun deck for use in case a lock should fail. Down below the frigate’s waterline, the gunner and his assistants opened the forward and after magazines and began to break out sausage-shaped flannel powder cartridges for the guns and carronades. Other men took stations along the lower decks to pass cartridges up to the gun crews.

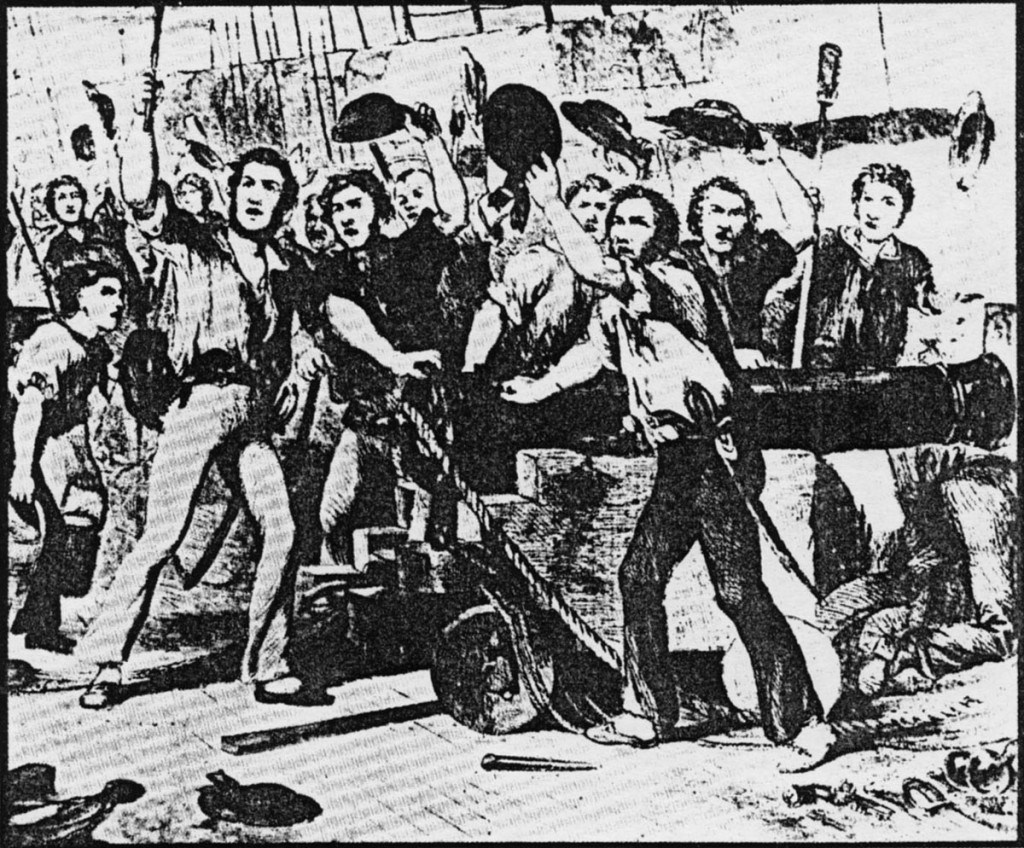

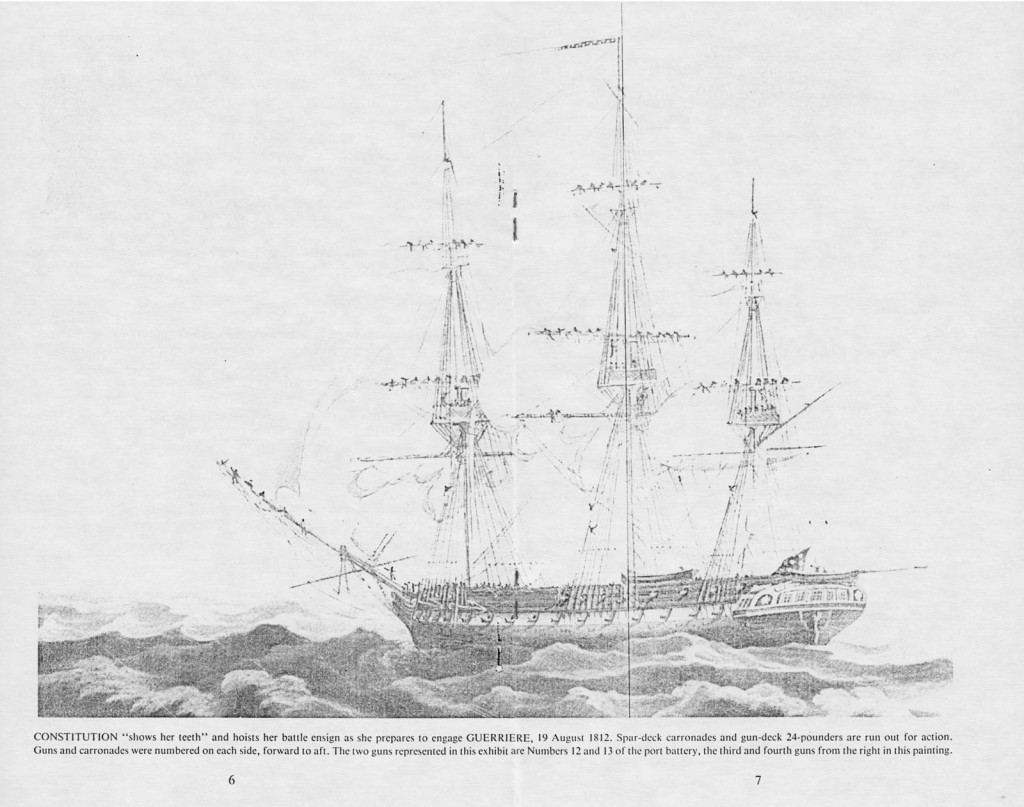

CONSTITUTION “shows her teeth” and hoists her battle ensign as she prepares to engage GUERRIERE, 19 August 1812. Spar-deck carronades and gun-deck 24-pounders are run out for action. Guns and carronades were numbered on each side, forward to aft. The two guns represented in this exhibit are Numbers 12 and 13 of the port battery, the third and fourth guns from the right in this painting.

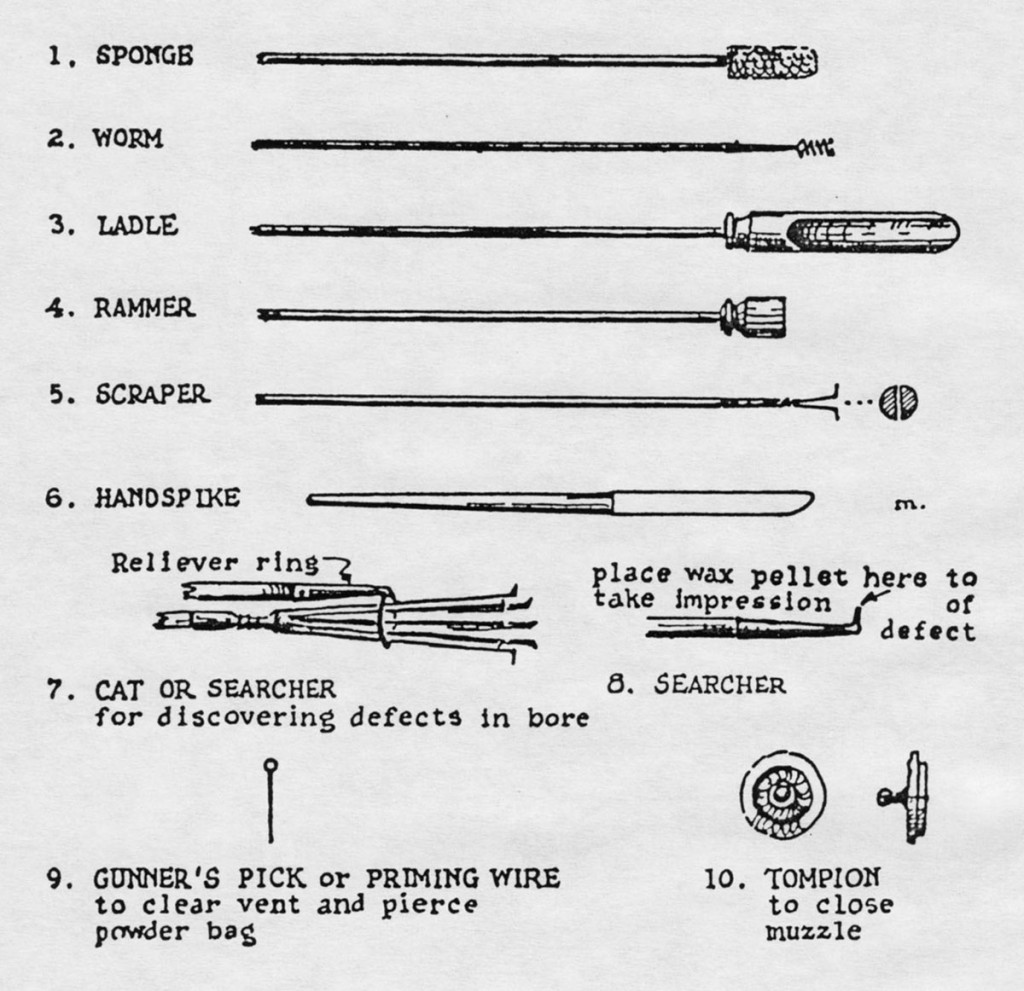

Tools of the gunner’s trade (not to scale). The sponge, moistened with water, extinguished sparks in the bore after firing. The worm cleaned unburned fragments of cloth powder bags from the bore. Ladles were originally used to load powder; after cartridge bags came into use, they were used to extract loads from muzzle-loaders without firing. The rammer sealed cartridge and ball in place; the scraper and searchers were used to clean the gun and to find damaged spots in the bore. The handspike helped to move the gun carriage and to raise the gun breech so the wedge-shaped quoin could be moved to adjust the gun’s elevation. The priming wire pierced the powder bag to make sure that the flame of the primer would ignite the powder charge, while the tompion kept the bore dry while the gun was not in use. (From Albert Manucy, Artillery Through the Ages (Government Printing Office, 1949).)

As Constitution drew near to her enemy, all was made ready. The captain took his station on the quarterdeck, from which he could direct the helmsman and order the handling of guns and sails. The marine detachment took their positions with loaded muskets, some on deck and others in the fighting tops. Gun crews checked the loads in their massive weapons and waited in silence for the action to begin.

When Constitution was within reasonable shooting range of her adversary—usually no more than a few hundred yards—the gun-port lids, which kept wind and spray out while cruising, were opened. At the command “run out!” men pulled on the side tackles to roll their guns forward until the muzzles protruded through the ports. One of the gun crew thrust a wire pick through the vent to pierce the cloth powder bag, inserted a priming tube (a length of quill, packed with fine powder) into the vent, and then primed the pan of the firing lock–similar to the locks used in flintlock firearms–with fine powder from a flask or horn. The lock was cocked, and the gun captain–the senior enlisted man of the gun crew–took the end of the firing lanyard and stood, knees flexed, behind the gun and sighted along the barrel.

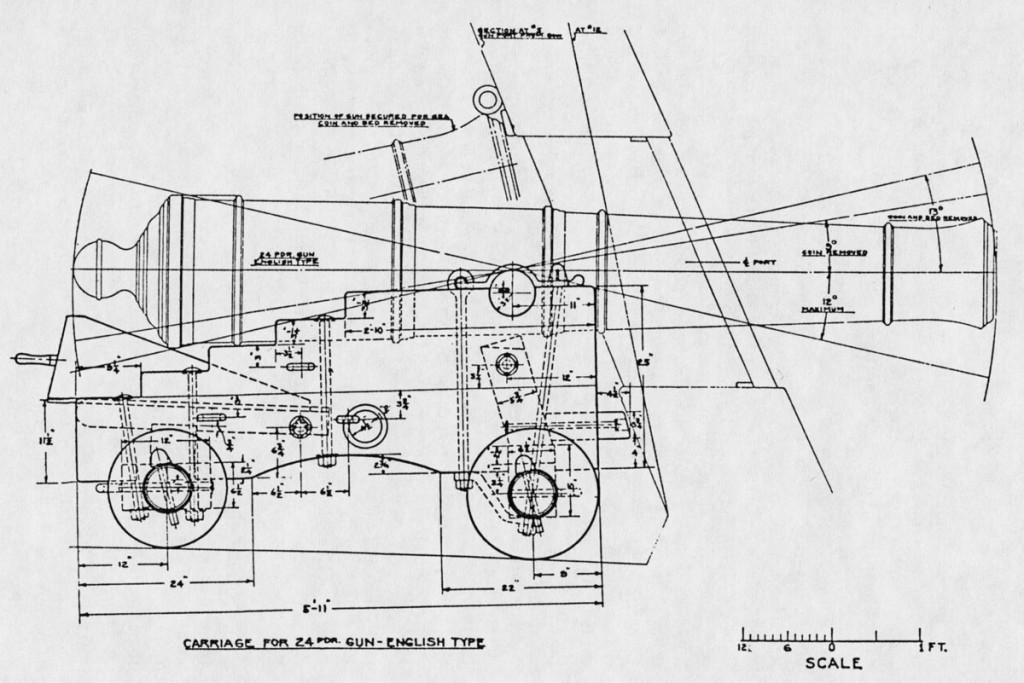

This scale drawing of one of CONSTITUTION’s 24-pounders illustrates the limit of elevation possible with the gun carriage of 1812 and shows how the gun was secured for sea when not in use.

The captain’s order to commence firing was passed by megaphone to the division officers, who then directed their guns. A ship’s guns might open fire together in a single broadside, or each division might be ordered to “fire as she bears.” As the target came into view through his gun port, the gun captain waited for the proper moment in the ship’s roll, depending on whether the object was the enemy’s hull or his masts and rigging. At the right moment, the gun captain pulled the lanyard to trip the firing lock. This struck flint against steel, sending a spark into the pan. The ignited powder in the pan sent a flame through the priming tube to set off the powder charge in the gun and hurl its 24-pound iron shot at the enemy with a reverberating thunderclap of sound and a swirl of whitish smoke.

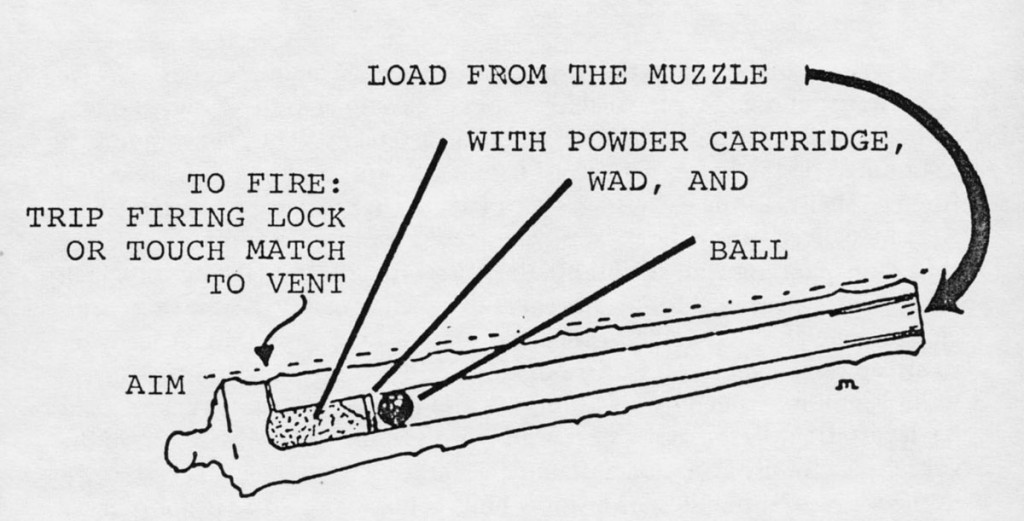

Loading and aiming a muzzle-loading smoothbore gun was simple in principle but required training and skill in practice. (From Manucy, Artillery Through the Ages)

For every action, as Isaac Newton told us, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The tremendous push needed to send a cannon shot on its way at many hundreds of feet per second also made the gun jump back on its carriage with great force. In a crowded space like the deck of a ship, this had to be controlled. Where a modern gun’s recoil is absorbed by combinations of strong springs and hydraulic cylinders, this gun depended on its heavy breeching to bring it safely to a stop. The bore was wiped out with a sponge moistened with water to put out smoldering bits of powder bag or grains of powder that might remain inside the gun. The powder passer, who shuttled between the gun and the lower-deck hatch to pick up powder charges from the gunner’s assistants, brought a flannel cartridge to the gun and handed it to the loader who pushed it into the muzzle. The cartridge was pushed firmly home with the rammer, and a wad of scrap fibers was rammed down after it. A shot man brought the iron ball from a nearby shot rack; the loader inserted the shot in the muzzle; then followed with another wad and rammed the load into place. The gun was now ready to run out, prime, and fire. In the earlier stages of an engagement, this might be done in an ordered fashion, with the ship discharging whole broadsides or firing by division to the word of command. When two ships finally came to close quarters, they usually began to fire at will, each gun loading and firing as rapidly as possible under the direction of its own midshipman and gun captain. At the close ranges of that day, effective shooting depended not upon pinpoint accuracy, but upon rapidity. When the target was looming only a few yards away there was no question of aiming, but simply of getting off as much metal as possible to overwhelm the enemy. While some captains, such as Stephen Decatur and the English Philip Broke, drilled their men in firing at longer ranges and taught accuracy and coordination of fire, many officers in the days of sail considered short-range rapid fire the principal test of a well-trained gun crew. The impact on eye, ear, and mind of this kind of close-range violence can only be imagined. As Louis de Tousard described it in 1809 in his American Artillerist’s Companion:

The havock produced by a continuation of this mutual assault may be readily conjectured by the reader’s imagination. Battering, penetrating and splintering the sides and decks; shattering and dismounting the cannon; mangling and destroying the rigging; cutting asunder or carrying away the masts; piercing and tearing the sails so as to render them useless; and wounding, or killing the ship’s company.

The iron solid shot was the 24-pounder’s principal ammunition. Explosive shells were not used in ship-to-ship actions at this time, as these were thought to be more dangerous to the user than to the enemy. Thus, naval guns of 1812 relied on the battering effect of solid shot rather than on the bursting force of shells. In the early stages of a frigate engagement, while two ships were maneuvering for the most advantageous position, a captain might try to use dismantling shot to disable the maze of sails and rigging on which his opponent depended for movement and maneuverability. As the ships drew close to one another, some of their guns might load with grape or canister to sweep the enemy’s decks. Use of this antipersonnel ammunition turned a ship’s gun into an enormous shotgun, and its effect at short ranges could be devastating. “Hot shot” were simply iron round shot, heated red in the galley stove for use against an inflammable target. The sizzling ball, embedded in the wood of a building or a ship’s hull, could ignite a fire if not quickly extinguished.

Since fire was a mortal threat to wooden warships, hot shot were only occasionally used in shore bombardment. Constitution did not use them in ship-to-ship actions.

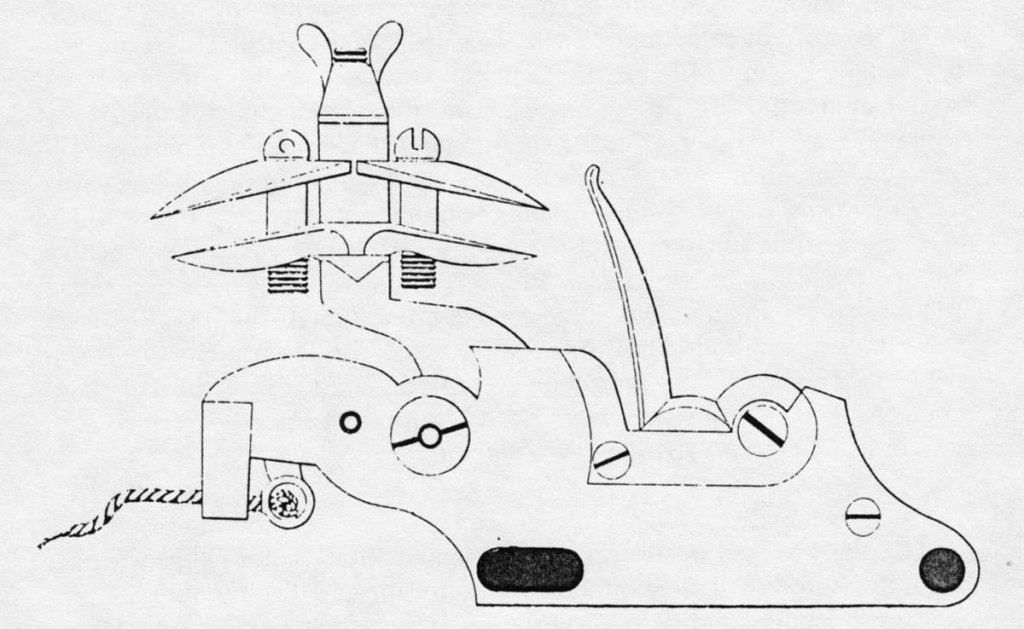

Flint firing lock of the type used in 1812. The double-headed cock holds two flints and could be quickly reversed if one flint became worn or lost. (From Sir Howard Douglas, A Treatise on Naval Gunnery (London, 1820))

The principal object of naval battle in 1812 was not to sink an enemy, but to batter him into surrendering. It was difficult to destroy a wooden warship with solid shot. Unlike naval actions of our own century, where ships were usually sunk rather than taken, relatively few wooden sailing warships were sunk in combat. Damage to his ship and casualties to his crew could compel a captain to surrender; in some actions the ships came alongside and the opposing crews attempted to board and fight it out at hand’s reach with small arms. Whatever the circumstances, war at sea in those days of our ancestors was hardly for the timid. It took a special kind of courage to “stand to your guns” at ranges measured in scores of yards, Wooden ships and smoothbore guns look picturesque today; to the men of 1812, they were everyday reality, some of it quite grim by any standard. May this display help all of us who see it to remember that our nation has been built and maintained by the effort and sacrifice of the generations that have gone before us. And may it also remind us that, now as then, the physical capabilities of machines are always less important than the qualities found in the minds and hearts of the people who use them.

For Further Reading

Tyrone G. Martin, A Most Fortunate Ship; A Narrative History of “Old Ironsides.” Chester, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 1980. (A former commanding officer of Constitution presents a carefully-researched, readable account of her career.)

Howard I. Chapelle, History of the American Sailing Navy. New York: Norton, 1949. (Design study of the evolution of sailing warships in the American navy, with illustrations and numerous ship plans,)

John Masefield, Sea Life in Nelson’s Time. London, 1905. Third edition, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1971. (Daily life and war at sea in the British navy. Though some details of American naval life differed, this work offers a valuable appreciation of life in a sailing man-of-war.)

Albert Manucy, Artillery Through the Ages; A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1949. (Kept in print and currently available, this is a helpful introduction to the general subject of early artillery on land and sea.)

Peter Padfield, Guns at Sea. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1974. (General illustrated history of naval guns and gunnery from the introduction of gunpowder through World War 11.)

Harold L. Peterson, Round Shot and Rammers. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1969. (Generously-illustrated introduction to muzzle-loading artillery as used in the United States. Though Peterson focuses on land, rather than naval, gunnery the two had much in common.)