By PHC Milt Putnam, USN (Ret)

June 27, 1969 – Naval Air Station, Imperial Beach, California

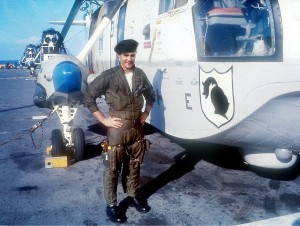

Photographer Milt Putnam standing alongside a Sikorsky Sea King helicopter on the deck of aircraft carrier USS Princeton, May 1969, for Apollo 10 recovery mission (Photo by Ralph Howard)

A banging on my door at Naval Air Station, Imperial Beach, California, shook me out of a deep sleep. It was 4 AM. Bill Case, a Senior Chief Journalist, from Pacific Fleet Headquarters Hawaii, was there with a big smile on his face. He asked, “Is your bag packed? We’re leaving for the Apollo 11 recovery this morning.” I replied “Take off time for USS Hornet is 10 hundred hours.” We talked for about an hour and finally he crawled into an empty bunk in my room so we could get a couple hours sleep. Bill and I had become friends during the Apollo 8 recovery, December 1968 on USS Yorktown, and Apollo 10 recovery, May 1969 on USS Princeton. Apollo 8 and 10 were the first manned flights to orbit the moon.

In late June, eight HS-4 helicopters with “Black Knight” flight crews landed on USS Hornet (CVS-12) seventy-five miles off the California coast. At Pearl Harbor the ship was loaded with additional recovery equipment, and US Navy Underwater Demolition Team 11 (UDT-11). Also boarding were civilian television crews, magazine, newspaper photographers and writers, including my photography friends Walter Green and Berry Sweet of The Associated Press and Pete Cosgrove with United Press International. Lee Jones, a NASA motion picture photographer, also joined us. Lee would fly the Apollo 11 recovery mission with me as he had during the Apollo 8 and 10 recoveries.

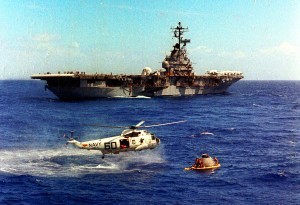

During practice recovery July 11, 1969, Navy UDT swimmers (wearing orange and standing on flotation collar) finish attaching the flotation collar around a dummy capsule, with USS Hornet in background. (Photo by Milt Putnam, HS-4)

For the first two weeks of July, off the Hawaiian Coast, Hornet, the helicopter crews, and UDT-11 got down to business training for the recovery of Apollo 11. It was practice, practice, practice in preparation for the real thing on July 24. During simulated recovery exercises UDT-11 swimmers jumped from helicopters into the Pacific Ocean and swam to the nearby training capsule (called a boilerplate) where they attached flotation collars to the dummy spacecraft, and playing the part of astronauts, were hoisted into helicopters time after time.

I flew in the Photo Helicopter shooting pictures for Navy and NASA archives. Several of my practice photos were released via the Associated Press and United Press International. Those images were published in newspapers and magazines throughout the country. Determined to study how rapid the Pacific light would change during the actual recovery, I began taking light exposure readings with a hand held lightmeter every minute or two on early morning practice flights.This taught me how often the exposure settings on my cameras would need to be changed. Those readings were recorded in a small notebook that has since been lost. (All of my Nikon cameras did not have built in light meters.)

Liftoff

On July 16, Apollo 11 launched from Florida. At that time, Hornet was about 1600 miles southwest of Hawaii at the Primary Launch Abort Area. If the astronauts had to make an emergency landing in the Pacific before leaving earths atmosphere this was the location. We heard the Apollo 11 launch broadcast over the ship’s radio and knew the astronauts were underway. Within three-hours of takeoff from Florida and over the Pacific Ocean the spacecraft blasted out of earth orbit toward the moon. (Hornet being so far from land, we were not able to see the launch on television). USS Hornet then sailed north to the Primary Recovery Site, 1200 miles southwest of Hawaii. For the next week, practice recoveries continued, each day starting before dawn and lasting through early evening in all kinds of weather. During this time frame, 16 or 17 training recoveries were completed.

The lunar module piloted by Neil Armstrong touched down on the moon on July 20 – “Houston, Tranquility Base here, The Eagle has landed.” As Armstrong spoke those words, everyone listened closely through crackling static air waves on the ships radio. Two and one half hours later we heard, “That’s one small leap for man, one giant step for mankind.” Armstrong was the first man to step onto the moon. Hornet was on station (splashdown recovery site), practicing and awaiting the astronauts return to earth.

Deteriorating weather with rain, high winds and rough seas approached the Primary Recovery Area and caused much concern on July 22. The Navy and NASA decided it was best to move the splashdown site to another location 250 miles from the storm. USS Hornet steamed at full speed to the new location 950 miles southwest of Hawaii. A few of the crew wondered if we’d be late for splashdown.

Meanwhile, we continued to test out cameras and equipment. Walter Green and I mounted two motorized Nikon cameras (fitted with a 28 mm lens and a 35 mm lens) about 12-15 feet high on the Hangar Bay bulkhead (wall). We would fire the cameras by electronic remote when the astronauts walked from helicopter #66 to the Mobile Quarantine Facility. The MQF was a silver Airstream trailer that would house up to six people. Walter and I shot test film to ensure the exposure, focus and area covered by the lenses were correct. In 1969, cameras did not have automatic focus and exposure control, everything was done by hand and eye. Satisfied with the test, the cameras were reloaded with Kodak black and white and color film and left on the bulkhead overnight awaiting the next day’s arrival of the astronauts.

A group of photographers, including myself, were sitting around shooting the bull when “Taps” played over the ship’s speakers at 10 PM, indicating bedtime. No one was sleepy – to tell the truth, we were a little nervous knowing that within a few hours we all would be photographing the first men to land and walk on the moon. It was near 12:30 AM when I went to bed, and still I could not sleep.

Three hundred hours (3 AM civilian time) on July 24, Apollo 11 Recovery Day, all hands involved with the recovery were up moving around and having breakfast. After breakfast, helicopter crews reported to the flight ready room. We received the latest weather reports, nearest distance to land, and last minute instructions about splashdown times and location. One helicopter would be on station a few miles behind USS Hornet, another the same distance in front. The primary recovery helicopter and the photo helicopter would circle the ship a mile or two out.

Preflighting the helicopters (making sure everything was operating OK) went fast and we lifted off the carrier in the dark. The sea air was balmy as it whipped through the open hatches. Rotor blades beating the air sent vibrations through everything and everyone inside. On board the photo helicopter, I had eight Nikon cameras. Only two had motors, the other six would have to be cocked by thumb. Lenses ranged from a 35 mm up to a 300 mm (no zoom lenses). Also in the camera bag were 60 rolls of Kodak Tri-X film and 15 rolls of Kodak color.

My primary duty was to shoot black & white for immediate release through the Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI) wire services. By using the AP and UPI, my recovery images would be transmitted to magazines and newspapers throughout the world.

In 1969 civilian press photographers were not allowed to fly in military helicopters. It was my job to photograph the splashdown, the UDT-11 swimmers attaching the flotation collar around spaceship Columbia to secure it in the tossing seas, the astronauts leaving Columbia and crawling into the life raft, and Columbia being hoisted out of the sea by the helicopter. And then back aboard Hornet to photograph the President talking with the astronauts.

Splashdown and Recovery

It seemed like hours sitting high above Hornet waiting for Apollo 11 to arrive. Everyone was watching the dark morning sky, even though we all knew she would not arrive early. Word came from Hornet a few minutes before 6 PM (Hawaiian time), that Apollo 11 had been picked up on radar and would splashdown twelve miles downwind from the ship. I lowered the port hatch (door on the left side) on the photo helicopter. Lee Jones and I would sit side by side on the hatch steps shooting pictures of the recovery. While lowering the hatch my lightmeter cord became tangled and broke. The meter dropped into the sea and sank.

Standing in the helicopter’s hatch, Navy UDT swimmer LT Clancy Hatleberg gets set to jump into the water. (Photo byMilt Putnam,HS-4)

Helicopter #66, the primary recovery helicopter, and the photo helicopter #53, approached the splashdown site in predawn darkness to find Columbia upside down and bobbing in fairly calm seas. The astronauts sitting upside down in Columbia pushed a button to inflate three large flotation balloons to upright their craft. My helicopter moved to the right 100 feet and hovered at 40 feet. We would stay at that spot until all three astronauts were hoisted into the recovery helicopter. Commander Don Jones, flying helicopter #66, slowly moved in and dropped a marine location marker (green smoke bomb). At the break of dawn, one of the helicopters with the UDT-11 swimmers hovered near Columbia and three swimmers jumped into the ocean. A second helicopter following closely dropped life rafts and the flotation collar that would be used to help prevent Columbia from sinking. It took only a few minutes for the swimmers to attach the flotation collar and position the life rafts. It was getting lighter by the second and I was already firing the Nikons, shooting whole 36 exposure rolls of film before changing to another camera and lens. Lee Jones, the NASA photographer seated to my right, had his 16 mm motion picture camera rolling as well.

The primary recovery helicopter made a slow pass near Columbia. Navy Lt. Clancy Hatleberg, the senior UDT-11 swimmer, jumped ten feet or so into the water and swam to the command module. The next helicopter used its rescue basket to lower a bag containing four uniforms never worn by space travelers before. The uniforms, biological isolation garments, were worn by the astronauts and Hatleberg during recovery because it was unknown if the astronauts would return to earth from the moon carrying some kind of germ or virus that would cause harm. Hatleberg slipped into one of the biological isolation garments while the other swimmers in a raft moved 100 feet upwind from Columbia.

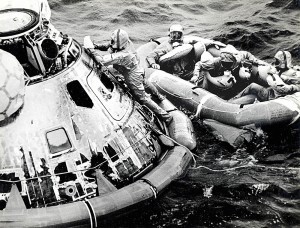

Looking on as Navy UDT swimmer LT Clancy Hatleberg closes the capsule’s hatch, astronauts Michael Collins, Neil Armstrong (center) and “Buzz” Aldrin, sit in their life raft. (Photo by Milt Putnam)

At 6:20 AM, Hatleberg quickly open the command module hatch and tossed in three remaining uniforms and closed the hatch just as quickly. After a short wait, Hatleberg opened the hatch again and out came three moon adventurers covered head to toe wearing biological isolation garments. Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin settled at each end of the life raft. Neil Armstrong sat in the middle and watched Clancy Hatleberg closely as he closed Columbia‘s hatch and locked it down. Hatleberg sprayed a decontaminate over the module and around the hatch. He then wiped down each of the astronauts with a sodium hypochlorite solution to kill any moon germs that may have gotten on their BIG suits before they exited the command module

The primary helicopter #66 moved over the spaceship and astronauts, lowering her rescue net to hoist each astronaut one at a time into the helicopter. If I had jitters they were gone – the job at hand was foremost on my mind and I was shooting pictures as fast as possible. My mind was on automatic – shoot a few pictures, change the f/stop a little, ensure the next camera was still set on 1/250 of a second shutter speed, check the f/stop. Remember that the shutter speed would soon have to be reset at 1/500 of a second because the light was getting brighter. Shoot another roll of film, load film, etc. The light exposure readings recorded in a notebook during practice recoveries never came out of my pocket. In fact, I didn’t even think about it.

When the last astronaut was lifted from their life raft into the recovery helicopter the photo helicopter raced back to Hornet. It was also Lee Jones and my job to photograph the astronauts as they stepped from the recovery helicopter and walked into the Mobile Quarantine Facility where they were to spend the next three days. On the way back to the carrier, I stuffed 52 rolls of exposed film into the zippered pockets of my flight suit and 8 or 10 rolls of unexposed film into another pocket. I loaded three cameras to use in the hangar bay for when the astronauts arrived. I left five Nikons and the remaining unexposed film on the helicopter for pickup later.

The photo helicopter was the first chopper back aboard Hornet. I jumped from the helicopter to the flight deck (about four feet) without realizing I was still wearing my safety belt. It was still connected to the inside of the helicopter. Toes barely touching the deck and cameras swinging from my neck and shoulders, I almost fell over before setting a speed record in getting out of a safety belt. If anyone noticed or saw my predicament no one said a word.

President Richard M. Nixon

Walking across the flight deck, I noticed the President of the United States, Richard M. Nixon, watching the incoming helicopters. I stopped and shot a few pictures for the naval archives and then proceeded on to the hangar bay. President Nixon and several of his staff had arrived thirty minutes before splashdown. The Presidential secret service were on Hornet a day or two before the President arrived ensuring it was safe for his visit. As a safety factor, the flight crews were ordered to turn in all weapons. We were allowed to fly with our very sharp six inch blade survival knives. The knives were needed in case a helicopter went into sea with sharks present, or it could be used to cut and saw through thick Plexiglas windows to get out of a sinking helicopter. Lee Jones and I worked our way through hundreds of sailor (who were trying to see the astronauts and President) to our assigned spots in the hangar bay. Our location was right in front of the MQF where everything would take place. We joined dozens of news photographers and writers who were also covering the recovery and the President.

The Apollo 11 astronauts landed on Hornet, thirty-seven minutes after Clancy Hatleberg had opened Columbia‘s hatch the first time. Helicopter #66 was towed to an elevator and lowered to hangar bay level where the Mobile Quarantine Facility awaited. As the astronauts walked to the MQF, I remembered to fire the bulkhead mounted Nikon electrically. Those pictures really helped to tell the story of Apollo 11’s recovery.

One of my best photos of the day was taken in the hangar bay of President Nixon speaking to Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin through the MQF glass window. The President was telling a joke about astronaut Frank Borman. (Borman was Command pilot of Apollo 8, first flight to orbit the moon.) The picture shows Armstrong leaning down and looking to his right trying to see Frank Borman. Buzz Aldrin and Mike Collins are laughing. The president is shown pointing toward Borman and laughing at the joke.

President Richard Nixon asks Photographer Milt Putnam to send him photos of the recovery (Photo by Unknown)

Knowing the President would be leaving the ship shortly after talking with the astronauts, I ran to the flight deck to get pictures of him shaking hands and speaking with some of the sailors. On the flight deck, a long line of men were waiting for the President. As I came alongside the sailors, President Nixon appeared through an open hatch and stepped onto the flight deck. Immediately a secret service man stepped behind me and placed a hand on my left shoulder. Walking backwards taking pictures of the President shaking hands, the secret service guy stayed with me step for step. Suddenly I bumped into him and instantly both his hands were on my shoulders and he said “This is as far as we go, bub.” We were near the Presidential helicopter. Later I realized the Navy survival knife was still attached to my flight suit. President Nixon stopped in front of me. We shook hands and he ask if I would send him pictures of the recovery. He then boarded Marine ONE and lifted off for Johnston Island 250 miles away.

Developing Film and Making Prints

Walter Green (Associated Press) developed all my film. Upon seeing how many rolls of black and white film I had, he said, “Bet you didn’t miss much,” and I said, “Walter, If I did miss something, I couldn’t ask Neil to do it again.”

As Walter finished developing several rolls of film at a time and it dried, Barry Sweet (Associated Press) edited the first run of film and chose five of my images shot from the photo helicopter, and four he and Walter had shot on the ship. I started printing and drying the pictures at a rapid pace. This completed, Barry typed captions for the photos and I stuck the captions on the prints. Each photo was transmitted singly over the wire service transmitter. Transmitting a single print was about a fifteen minute process.

Barry and Walter’s orders were to transmit the recovery pictures directly to Associated Press Headquarters in New York. There the AP editors would do a second edit and release everything to magazines and newspapers. We had been transmitting for about an hour when someone came running in with a message (telegram) from AP New York.

It read, “Stop transmitting to NY, receiving double images. Retransmit everything through San Francisco.” Here we were sitting in the middle of the Pacific Ocean transmitting pictures that were going both ways east and west around the globe creating a double image in New York. It took thirty minutes to connect with San Francisco.

Walter continued developing film. When it dried he and Barry selected more images for me to print and make ready for transmitting. I have no idea how many pictures we placed on the AP wire that day, July 24, 1969, but it must have been 25 – 30 prints. It was midday when Pete Cosgrove (United Press International) came by the AP transmitting room and asked if he could use a few of my recovery photos. He selected the astronauts seated in a raft with Clancy Hatleberg at Columbia‘s hatch and the three astronauts being hoisted into the helicopter. Also selected was one picture taken with the bulkhead mounted camera of the astronauts walking to the MQF.

Recovery Day Comes to an End

At the end of a very long day, I gathered up all my film, put it in envelopes and safely stored it in a locker with my cameras. This film would be captioned on the way back to Hawaii and later mailed to the Naval Photographic Center, Washington, DC. Lee Jones (NASA) had already collected the color film, which would be developed by NASA. I had not eaten since breakfast, but I was so tired by 8 PM that I laid down on my bunk still wearing boots and flight suit to rest for a couple of minutes before hitting the shower. I awoke at 6 AM the next morning still dressed.

The next day, Walter Green found me in the mess hall. He had a telegram from AP New York that read newspapers around the world had used more pictures that I had taken from the photo helicopter than any others. Years later a computer check showed that my photography took up nearly two-thirds of the front page of the Chicago Tribune and nearly half of the front page of The Washington Post. Newspapers in Los Angles, St. Petersburg, London and Japan also carried my pictures.

On July 26, the Mobile Quarantine Facility (with astronauts inside) was lifted off Hornet and transported on a flatbed trailer to Hickam Air Force Base and flown to Houston aboard a USAF C-141. Lee Jones was also departing the ship, but before leaving he gave me a piece of Mylar from the command module Columbia. This mylar had orbited the moon while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were walking on the moon’s surface. It also was part of the spaceship’s shielding against radiation while in space.

Everyone involved with the recovery had the next day off. A couple of friends and I went to Waikiki Beach, walked around awhile, and then saw the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

USS Hornet sailed for Long Beach, California on July 28, following a very successful and historic mission. We were two days away from the California coast when I received a telegram informing me that my grandfather Andrew Brown Carver (he was known as Dude Carver.) had died at age 73. Commander Don Jones (Commanding Officer HS-4) offered to fly me off the ship but knowing I could not arrive in South Carolina in time for the funeral, I chose to remain on the ship and remember him as he looked the last time we met. A couple days before leaving Imperial Beach for the Apollo 11 recovery in June, I had called my Grandfather at the hospital, and we spoke for about 15-minutes. When Orville Wright made the first airplane flight December 17, 1903 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, my grandfather was seven-years old. During his life he had seen aviation grow from that first flight, to watching the first men to walk on the moon via television in his hospital room.

It was mid-morning August 1 when Helicopter Squadron Four’s helos lifted from Hornet‘s flight deck for the three-hour flight to Naval Air Station, Imperial Beach.

Thinking Back

In a lifetime of taking pictures, I can safely say, I’ve never had a more exciting photographic assignment than the Apollo 11 recovery, over 40 years ago. Some of the memories from that day seem like yesterday. I can still hear the wop-wop-wop noise from the photo helicopter rotor blades and feel the vibration throughout my whole body. I can still feel the warm humid air from the rotor blades washing over me and throughout the helicopter.

I can still hear the photo helicopter pilot and co-pilot talking through the ear-phones in my helmet. Pilot – “Hatleberg is about to jump.” (Meaning the UDT-11 swimmer is about to jump into the ocean). Co-pilot – “He’s jumping close”. (Meaning close to the command module). The pilot asks me-“is the wing high enough.” (Meaning, is the rotor blade out of the pictures.) I answer, “Yes Sir, we are doing good.” Pilot -“Recovery-one is hoisting Armstrong”.

It was a tingling thrill to see the astronauts crawling out the command module into a life raft. I thought, these men just returned from the moon. My adrenaline was pumping, faster than the Nikon camera motors could shoot.

I’m very proud to have been chosen to photograph history.

I always stand a little taller when I see one of my recovery pictures in a library book, a magazine, newspaper or anywhere. I think – wow, those pictures will be seen forever.

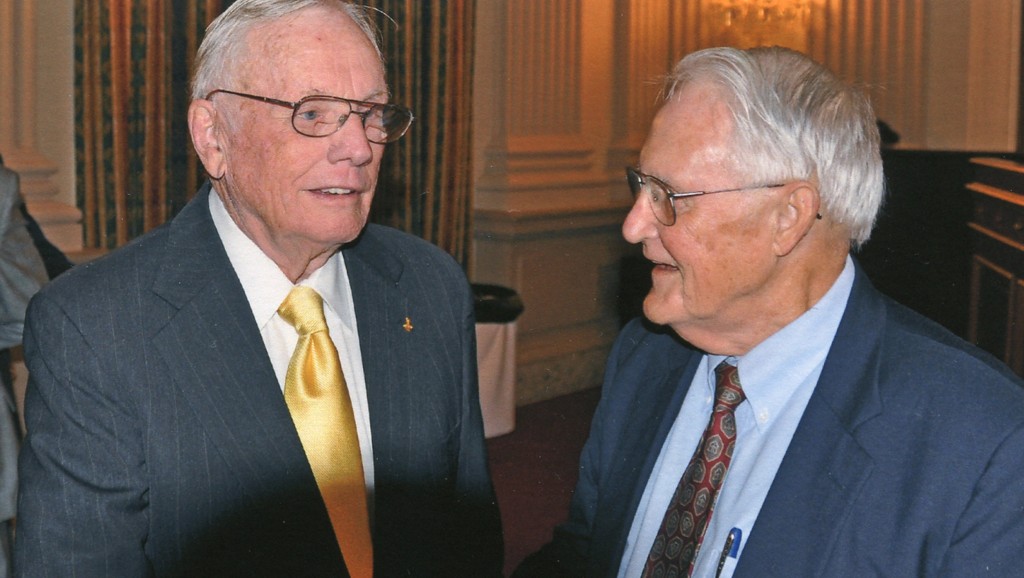

Milt Putnam retired from the Navy in 1979 as a Chief Photographer’s Mate. In addition to covering the recovery of Apollo 8, 10, and 11 for the Navy, he photographed the Queen of England’s visit to Boston, a three-month expedition to Antarctica with The National Science Foundation, the return of POW’s from Vietnam, and earthquake relief in Peru. He later worked for several newspapers, and as Director of Photography for the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agriculture. Sciences. In November 2011, Putnam, along with others from the Apollo 11 Navy recovery team, was invited to attend the ceremony awarding Congressional Gold Medals to astronauts John Glenn, Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin, see photo below. Footage of the ceremony can be found on C-SPAN, including specific mention of USS Hornet and the recovery crew at about 1:30 in to the video.

Neil Armstrong greets Milt Putnam in November 2011. Putnam was the primary military photographer covering Apollo 11 from its splashdown in the Pacific until President Nixon joked with the astronauts in their Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) aboard USS Hornet. (Photo by Capt. Bruce Johnson, USN, Retired)

Michael Wheat

Don Blair

Susan Wood, Susan Wood Photography

Barry Sweet

Richard (Rich) Barrett

Steve Muench

Rich Barrett

D Dean

Jessica Byers

Bryan Thornhill

Brandon Jones

Mary Mattson

Patricia Lee Jones Akrabawi

Peter Cosgrove

Barry Sweet

Dan Bernath PH2

Peter Cosgrove

Barry

Peter Cosgrove

Barry Sweet

Peter Cosgrove

Tom McTigue

Alfred Hassebrock

Joel Petersen

John King

Susan L. Meadows Fortner Richardson

Susan L. Meadows Fortner Richardson

Hizuru Wenzelburger

Rolf Sabye

MaryFrance Boulden

Robert Madden

Forrest Robinson

Rolf Sabye

jeremy moore

Brian Mensch

MaryFrance Boulden

Barry Branham

Barry Branham

MaryFrance Boulden

Chris Deets

Roger J Duclos (ITC retired)

Gary Smith

Fred Tonge

Wendy Papagan

Joe Holt

B. Schulze

Darryl Smith

Charlie Johnson

Marie Wright-Pugh

John Piechota

Deborah Frerking

Stephen Bramham

Gary McPhee