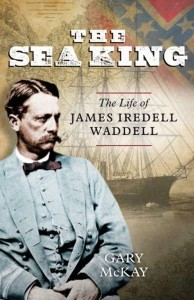

By Gary McKay, Birlinn Limited, Edinburgh, (2009)

By Gary McKay, Birlinn Limited, Edinburgh, (2009)

Reviewed by John Grady

James Iredell Waddell is long overdue for a full-blown biography; and Gary McKay comes close to providing it. In the last five years, the commerce raider he commanded, CSS Shenandoah, and its around-the-world attacks on Union shipping -particularly the North Pacific whaling fleet — has been the subject of at least three popular works – Last Flag Down, The Last Shot, and Sea of Gray. All are strong on narrative; all are weak on endnotes, chapter notes, or footnotes.

Like the three books mentioned, McKay’s work is a popular biography, drawing heavily on Waddell’s papers, many of them in the North Carolina state archives and the University of North Carolina, and the Naval History and Heritage Command at the Washington Navy Yard. For perspective McKay also properly drew on published collected memoirs, including Waddell’s, his second in command William C. Whittle Jr’s, and the commander of Sumter and Alabama Raphael Semmes’. As seen in McKay’s book, Whittle in his 20s had his share of Semmes’ daring. Semmes’s connection to this biography also includes Irvine Bulloch, the sailing master of Shenandoah and a veteran of Alabama.

Semmes, particularly in Memoirs of Service Afloat, comes across as a dashing figure, while Waddell, in his own memoirs and this book, comes across as moody and a man capable of carrying a grudge as he did against Union Navy Secretary Gideon Welles over back pay.

The book has some very strong points. McKay captures the tension of Waddell’s ordering Whittle “to strike down the battery and disarm the crew” on August 2, 1865 superbly. The irony of the August 2 date lies in the fact that it also was the day that President Andrew Johnson declared Waddell and his crew pirates (think Somalia and terrorists). For months after Appomattox, Shenandoah, originally named Sea King in a not-so-subtle attempt to get around suspicious Union consuls and spies as to the ship’s true nature and Great Britain’s foreign enlistment laws, had feasted on the American whaling fleet.

Until he lay off the coast of San Francisco, Waddell had no sure way to know how the Civil War was progressing. Like David Porter in the War of 1812, he was doing his best to wreak havoc on unsuspecting merchantmen in the Pacific. Unlike Porter, he never had to fight the climactic battle with his enemies there. He faced his own terrors.

Unlike many other Confederate commanders, Waddell had an advantage in his ship. It was originally designed to be a troop transport in the India service and was not hurried out a yard with barely serviceable engines as Customs and port agents closed in. It also had advanced sails and could pull its propeller out of the water to increase its speed while relying on the wind. More importantly, Shenandoah had a fresh water distillation unit aboard, reducing needed calls ashore.

When Waddell knew that the war was over, he was determined to return the ship to Great Britain come what may and not surrender it in an American port or to a Union commander.

Like many a Navy officer, Waddell’s strong family connections in North Carolina politics especially George Badger, then Navy secretary, won him an appointment as an acting midshipman in September 1841. He was not a quiet young man and took offense at perceived slights quickly. Within a year of coming onto active service, he fought a duel that left him with a serious hip injury and a permanent limp.

His record in the Mexican War was undistinguished. At the height of the war and with six years in the Navy, Waddell was ordered to the new Naval School at Annapolis. It was there that he met and later married Anne Sellman Inglehart, the daughter of a capital merchant. His career in the peacetime Navy was predictable with a few touches of adventure, like his final one when USS John Adams called in Siam. It was when John Adams called in St. Helena in the South Atlantic in November 1861 that he learned the Civil War had begun.

McKay skillfully puts Waddell, who had served in New Orleans and along the James River below Richmond, into the British world of shipbuilding in mid-1863 along the Clyde, the Mersey and the Thames and introduces dynamic characters, like James Dunwoody Bulloch, the senior Confederate naval agent in Europe and half brother of Irvine. He also tells well the frustrations Confederate naval officers felt waiting for a command that might never come, as was the case with Bulloch, and how even those who took command had to shuttle their families between England, Scotland and France to keep Union officials in the dark as to their whereabouts and orders.

The subterfuges again were very much in play when Waddell, selected by Flag Captain Samuel Barron, took his first command. First Sea King went on a series of short cargo trials with Whittle aboard making its way toward a dock on the Thames, its escape route. Like the other commerce raiders, it rendezvoused in international waters with a supply ship carrying the real commander, its guns, munitions and Matthew Fontaine Maury’s whaling charts.

Hunting had been good. By accepting the Confederate defeat and determined not to surrender, he was forcing ship and crew into a perilous odyssey. In addition to avoiding American ships and now Royal Navy ships, Waddell had to survive a near mutiny in his quest. His health was deteriorating; and even when they arrived in port it was touch-and-go for the crew. All could be held for piracy, but their good fortune held – including the British, Scot and Irish crewmen who all claimed to be Southerners. They fled into safety.

Waddell’s wife was not so fortunate. She was arrested in Maryland and was not released until the spring of 1866 and sailed for Great Britain to be reunited with her husband in exile.

McKay has captured quite well the twists and turns of Waddell’s life, including his post-war career. The shame of the The Sea King is that it is not more than what it set out to be – a popular biography. Waddell deserves more than that.

A retired journalist, John Grady also conducts oral histories on behalf of the NHF.