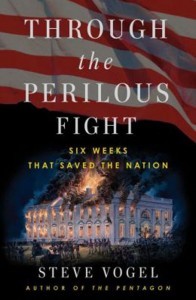

By Steve Vogel, Random House, New York, NY, (2013).

By Steve Vogel, Random House, New York, NY, (2013).

Reviewed by John Grady

Through the Perilous Fight is a wonderful and most welcome addition to the books commemorating the bicentennial of the War of 1812. Steve Vogel, veteran defense reporter for the Washington Post and author of The Pentagon: A History several years ago, tells the story of the sack of Washington and the defense of Baltimore with verve.

He humanizes the narrative skillfully by following two Americans, in particular, through these six weeks.

The first is expected: Francis Scott Key — lawyer, family man, militiaman “with no skills as a tactician,” and negotiator to free a Dr. Beanes being held prisoner by the British that was ultimately successful. The second is the ubiquitous and courageous 55-year-old gentle-faced Joshua Barney leading his flotillamen afloat and ashore against the British. Vogel certainly does not slight the travails of President James Madison and secretary of almost everything but the Navy at the time of the invasion, James Monroe. He spells out in telling detail the repeated failures of Secretary of War John Armstrong and General William Winder.

Vogel handling of the leading British figures in the Chesapeake campaign portrays Sir George Cockburn as: “the most hated man in America and the most feared.” In contrast, Vogel is more sympathetic in his treatment of Major General Robert Ross, one of “Wellington’s Invincibles,” and the man who captured Washington but regretted the burning of the Library of Congress. “I make war neither against letter or ladies,” a reference to Dolley Madison. He was killed a few weeks later in the fighting for Baltimore.

In his concluding chapter, Vogel analyzes the lessons learned from an unnecessary war. “The war’s many failures demonstrated the need for a regular army, with better officers and a superior military academy. The U.S. Navy was launched on a path toward becoming a global force, with steady congressional funding for ships.”

The need for a regular Army was driven home to Madison following the debacle at Bladensburg that barely slowed the British advance on the capital. At a dinner in the President’s House August 24, 1814, he told his guests, “I could never have believed that so great a difference existed between regular troops and a militia force if I had not witnessed the scenes of this day.”

Vogel, a colleague of mine when we both worked for Army Times Publishing Co., ably recounts how three Navy officers then ashore – John Rodgers, Oliver Hazard Perry and David Porter –rallied the Americans to defend Baltimore. It is a little known story, but “it was Baltimore’s good fortune that the three commodores, each waiting for new ships to be completed, happened to be available” serving amicably under a militia general, Samuel Smith.

With all that said, one lesson was put aside, as it was during the Revolution and would be again in the Confederacy. “The war – the Chesapeake campaign in particular – had exposed the military, social, and economic vulnerability of a nation dependent on slavery.”

Of course there are the stories of “The Flag,” flying over Fort McHenry “through the perilous fight” and “The Song,” today’s National Anthem, taken from notes “written on the back of a letter” as Key sat in a room in the Indian Queen Tavern following the bombardment. Their places in American history emerged gradually, almost without plan, but they are certainly fixed today as symbols of what citizens say the nation stands for – “the fire of liberty,” as Key called the Constitution during his July Fourth, 1831 address in the Capitol Rotunda.

A veteran journalist, John Grady conducts oral histories on behalf of the NHF.