By Norman Polmar

(Editor’s note: This is the tenth in a series of blogs by Norman Polmar, author, analyst, and consultant specializing in the naval, aviation, and intelligence fields. Follow the full series here.)

In the early 1960s, while researching my book Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events (1969), I encountered the massive, detailed series of reports produced by the U.S. government after World War II—the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS). A reading of the reports related to Japan at the end of the war indicated that Japan was about to collapse, even without the atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If true, on a very simplistic basis, that meant that there was no need to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

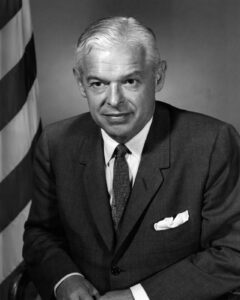

Fast forward to the late 1970s: In collaboration with my close friend Thomas B. Allen, I was writing a biography of Admiral H.G. Rickover, the long-time head of the Navy’s nuclear propulsion program. Through the efforts of Admiral Elmo R. (Bud) Zumwalt, who served as Chief of Naval Operations from 1970 to 1974, I was able to interview Ambassador Paul H. Nitze. He had key roles in the landmark U.S. defense strategy NS C-68, the Marshall Plan, the decision to develop the hydrogen bomb, the Antiballistic Missile (ABM)Treaty, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT), the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), and the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. Nitze had served as the Secretary of the Navy (1963-1967) and Deputy Secretary of Defense (1967-1969)—and had tried to get Admiral Rickover fired.

Air Force historian Lawrence R. Benson called Nitze, “arguably the most influential defense intellectual and arms negotiator of the postwar era….”

My interviews with Nitze for Rickover: Controversy and Genius (1982) went well. Subsequently, he asked me to be his guest for lunch at the Cosmos Club in Washington. We hit it off and began having lunch every month that he was in Washington, usually at the Tabard Inn on N Street Northwest. Admiral Zumwalt and a mutual friend, retired naval architect Edward Middleton, made our monthly get-togethers a foursome.

The discussions at lunch ranged far and wide, including the atomic bombings of Japan. In addition, usually Nitze’s driver brought him to the Tabard Inn and, after lunch, I would drive him back to his Georgetown home, giving me an opportunity for one-on-one discussions. (Later, as his health began to fail, we would have our luncheons at his home.)

Nitze had been a senior member of the European and Pacific USSBS and, he told me, he was one of only two members of the Pacific team with access to Ultra, the allied code-breaking effort. According to Nitze, the intercepts of Japanese communications, especially with their surviving diplomatic missions in neutral European countries in 1945, demonstrated that the Japanese government had no intention of surrendering prior to the atomic bombings. These comments led Tom Allen and me to the actual intercepts of Japanese communications, transcripts of which are in the National Archives. This material had a central place in our book Codename Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan and Why Truman Dropped the Bomb (1995).

Meanwhile, in 1989, Nitze published his autobiography Hiroshima to Glasnost: At the Center of Decision—A Memoir. At one of our lunches at the Tabard Inn he presented me with a copy of the book. I asked him to please autograph the volume, which he did. As he handed the book back to me, Zumwalt reached across the table and took it. Looking at the inscription, he said, “You got this wrong, Paul.”

Now I took the book out of Zumwalt’s hands and read:

To Norm Polmar, The great student of naval affairs.

My friend and frequent advisor. Paul Nitze

That from the personal advisor to five or six presidents of the United States!

“What’s wrong with this?” I asked. Zumwalt responded: It should read: “My frequent advisor on Washington bars and restaurants.” Nitze did not change the inscription. Okay for you, “Bud” Zumwalt!

Nitze repeated the USSBS conclusion in his book Hiroshima to Glasnost: “Even without the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it seemed highly unlikely, given what we found to have been the mood of the Japanese government, that a U.S. invasion of the islands would have been necessary.”

Yet, at several of our lunches at the Tabard Inn, one of which was attended by Tom Allen, Nitze repeated his contention that although Japan was in extremis, the leadership would not consider surrender. Rather, they hoped to inflict major casualties during the forthcoming U.S. invasion of Kyushu in November 1945, thus paving the way for favorable negotiations. He repeated this concept during at least one of our one-on-one discussions when I drove him home after lunch. Dr. Lawrence J. Korb, an Assistant Secretary of Defense during the Reagan administration, in reviewing Hiroshima to Glasnost, wrote: “Like others who write their memoirs, Nitze occasionally rationalizes and glosses over his own inconsistencies.”

From the Ultra intercepts of Japanese military and foreign ministry communication that Allen and I reviewed, these discussions with Nitze, and extensive research, Allen and I were convinced that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unquestionably justified in bringing the Pacific War to a rapid end.

Dr. Edward Teller, “father” of the hydrogen bomb, did not agree that it was necessary to drop the atomic bombs on Japanese cities; he believed that there should have been an atomic bomb demonstration for the Japanese. But that’s in the next blog.

Ray Robichaud

N Polmar

Dick Hallion

Pingback: The Truth About Hiroshima | Moral Low Ground

Pingback: Paul Nitze, Grand Strategy, and the United States Navy | Naval Historical Foundation