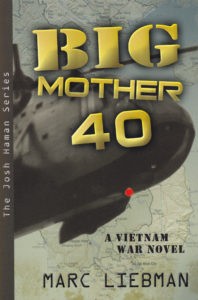

By Marc Liebman, Fireship Press, Tuscan, AZ, (2012)

By Marc Liebman, Fireship Press, Tuscan, AZ, (2012)

Reviewed by Thomas P. Ostrom

It was my pleasure to review this magnificent book about U.S. Navy helicopter combat rescue operations for downed aviators and crews during the Vietnam War. Naval Historical Foundation Program Director Dr. David F. Winkler suggested I review this book because of my own writing about U.S. Coast Guard history and that service’s Search and Rescue (SAR) legacy.

The USCG flew SAR missions with the U.S. Air Force in Vietnam in the Sikorsky “Jolly Green Giant” helicopters that author Marc Liebman chronicles in his exciting book, Big Mother 40.

Captain Liebman USN (Ret.) was an aviator in Vietnam and the Middle East. Liebman brought that background to the pages of this historical novel about the USN helicopter rescue crews that supported and extracted Navy SEAL combat surveillance teams in daring rescues behind enemy lines.

The author reconstructs HH-3A Jolly Green Giant SAR missions from land bases and off carrier and destroyer decks against Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army forces. The HH-3A helicopters carried crews of five in huge, heavily armored and armed aircraft designed to hover, land, and fly over dangerous landing zones and heavy grass and forests where enemy troops waited to capture downed American helicopter and fixed wing aviators.

Liebman guides the reader through complex military terminology, strategy, tactics, inter-service comparative ranks and rates, technology, ammunition and weapons, aircraft taxonomy, and an eclectic cast of soldiers, sailors, and intelligence operatives. Liebman’s military characters come from the USAF, USN, and USMC; and include the enemy: North Vietnamese soldiers (NVA), North Koreans, and Soviet (Russian) advisors.

Liebman provides essential historical and geographic background, and organized his story around realistic subdivided sections that include dates, times, and geographic locations in Indochina and the Philippines. The author takes the reader through scenarios that suggest the author’s significant familiarity with combat operations, communications and aviation technology, classified documents and briefings.

The objectives of the rescue teams were to “get in and out” safely, authenticate operational procedures, and avoid flying into enemy traps. Riveting accounts of combat action, and helicopter approaches and take-offs from hot Landing Zones are frightening enough to read about, let alone do.

Liebman’s vivid descriptions put the reader into the action, with phrases like, “The crew watched as the tip of the (helicopter) blades chewed through the top of the elephant grass,” with the enemy in close pursuit firing projectiles and bullets. And an aviator’s radio warning that his helicopter “is hit. Losing gas out of my left wing tank. Gotta go home.” And Liebman’s description of combat action with “the ping of bullets going through the skin of the helicopter.” And how an on-ground surveillance team discovers “the 10-foot chunk of a rotor blade that looks like it is from an H-3.”

The author discusses enemy acquisition of classified information, in one case discovered by a SEAL team after hand-to-hand fighting. The information was transmitted by surreptitious means, some coming from South Vietnamese “allies,” and American traitors. Liebman described how the USAF called upon USN aviators and SEALS to find the secret NVA missile base that was shooting down so many aircraft over North Vietnam.

Marc Liebman pondered and described the treachery: “I can’t help wonder how many of our Naval Aviators, Flight Officers (and other U.S. Armed Forces personnel became POWs, MIAs, and) perished because the Russians and their Vietnamese allies knew when and where we were coming. This is why the plot of Big Mother 40 has so many references to leaks in the communication system…”

The author wrote Big Mother 40 as a “tribute to those we lost because of traitors in our midst who put us at risk.”

Thomas P. Ostrom has written on Coast Guard history