This is the third of three articles that describe my experiences while serving as an engineer aboard commercial tankers in 1961. These articles provide a perspective on the different engineering practices between the Navy and Merchant Marine in the post-World War II era. (READ THE SECOND ARTICLE HERE)

In the summer of 1961, I relocated my family to the East Coast and looked for a full time civilian career. But nothing very promising had turned up, and money began to run out. I called the marine department at Texaco to see if they had another assignment for me. Sure enough, there was an immediate requirement for a relief Third Assistant Engineer aboard the Texaco Washington. I was to meet the ship the next evening in Bayonne, New Jersey.

I packed by bag and took a Northeast Airlines flight to New York. My brother in law met me at the airport and took me to the marine terminal. We arrived about 9 PM. I promptly changed my clothes and went below to meet the person that I was relieving.

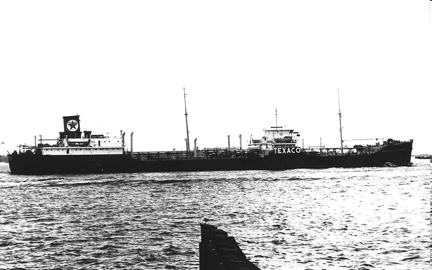

Texaco Washington was built at Sun Shipbuilding in Chester, Pa. as the S.S. Contreras, Hull No. 282. It was launched in April1943, about a month after its sister ship, Texaco Minnesota (ex. S.S.Churubisco), Hull No. 254.

The ship was basically a duplicate of Texaco Minnesota. It appeared to be in comparable condition. The only significant difference being that the propulsion plant was a Westinghouse vice a General Electric installation. The two vendors had somewhat different ideas on how to build a turboelectric propulsion system. But it was easy to cross deck between the two. After a couple of maneuvering watches, I felt right at home. The plant proved to be in fine condition, although it was not as much fun to steam as the one aboard Texaco Delaware. There was not as much crew stability as the two West Coast ships I served on. It seemed like we changed first and chief engineers every month while I was aboard.It was essentially an old person’s ship. I was the youngest member of the crew at age 25. The second youngest was the Master, who was 32. My fireman was 58 years old. Another was 66.

The ship was home ported in Port Arthur, Texas. While I was on board, its principal employment was to carry home heating oil from Port Arthur to ports in the Northeast. Our stops included Galveston, Wilmington, Camden, Bayonne, Carteret, Albany, Groton, Providence, Boston, and Portland.

There were some significant differences between tanker operations on the East and West Coasts where the climate was much milder. Port Arthur was very hot in the summer and the ships had no air conditioning or forced air ventilation in the machinery spaces where ventilation came by means of wind scoops. One of the oiler’s duties once underway was to go up to the top of the space and turn the wind scoops by means of hand cranks. This gave us the best possible conditions in the space, depending on which direction the relative wind came from. This worked out OK while underway, but it was of little use when dock side in Port Arthur where machinery space temperatures of 120° F were common.

In general, our trips from Texas to ports in the northeast were longer than those on the West Coast. We would always get a boost from the Gulf Stream when heading north and would run into it on the way South.Early on, at least two T-2 Tankers broke in half heading into a seaway. For this reason, Texaco policy was quite conservative on this subject. One of the watch engineer’s duties was to slow the ship down and inform the bridge whenever he felt the ship was under excessive stress while pitching when we headed into a seaway. Conditions in the after part of the ship made the engineer the perfect man for the job.

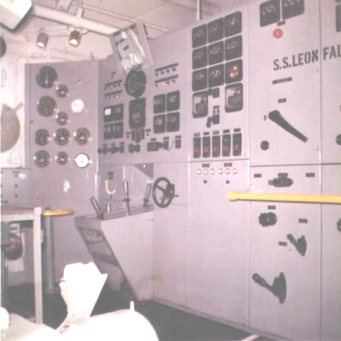

One day, I noted that a number of circuit breakers on the Main Switchboard had red tags on them. When I asked the First Engineer what they were for, he informed me that they were the breakers that had to be opened in the event we broke in half. It was a bit disconcerting. He hurriedly informed me that this had never happened to a Texaco tanker. Unfortunately, the SS Texaco Oklahoma did break up off Cape Hatteras in 1971. It was of a later design than a T-2.

About one month after I reported to the ship, we entered the Todd Shipyard in Galveston for a one-week overhaul accompanied by the annual Coast Guard inspection. On the way in, we stopped and anchored to empty and clean the port bunker tank. The entire unlicensed National Maritime Union (NMU) unlicensed engineering crew promptly quit. I remember the old adage, “When there are no Indians, the chiefs become Indians”. Since the officers were not covered by any union contract and the job had to be done, the second engineer and I were sent down into the tank to finish the job. I remember sitting down in the bottom of the tank mucking Bunker C heavy fuel oil residue up with a rag and reflecting that less than a year earlier I had been the XO/navigator on a minesweeper. It was a good character building experience. It took about a week of scrubbing to get the entire black, tarry residue off my back. The only consolation was Texaco’s policy to pay us “penalty time” (175%) for the time we spent in the tanks.

The shipyard period was interesting, to say the least. While we were in the yard, a hurricane came through and flooded out most of downtown Galveston. Meanwhile, we sat comfortably alongside the pier and rode it out. Fortunately, we were back on our own power by that time. We managed to get through a very intensive yard period that included cleaning and inspection of both boilers, the main condenser, main generator and motor, pulling the tail shaft, and a variety of other items in only one week. The engine room was a bit of a mess afterwards. But in three or four days, our four-man wiper crew had it back to normal.

It seemed as if there were a lot of misadventures and near misses during my time aboard Washington. Here are some anecdotes:

I always thought the procedure for getting underway without testing the system was a bad idea. When I asked the First Assistant, “How do you know it is going to work?” his response was “Well how do you know it will work a second time”. I still think I was right on this one. When we were leaving port one day, the first bell was a SLOW ASTERN. I pulled the lever back and nothing happened. It turned out that the problem was that I had not latched the door to the rear of the cubicle properly when shifting from Auxiliary to Propulsion service. The chief caught it right away and there was no harm done. It was a lesson learned.

On another occasion, I had just taken over from the First Assistant when we were entering port. On the first STOP bell, I noticed the main turbine rpm was creeping up from its normal idle speed of 1200 RPM. The First Engineer went over and whacked on the governor linkage with a hammer to no effect. By the time we got the next bell, the speed was up to about 2300 RPM. The Chief Engineer told me to go ahead and answer the bell. There was a big Wham and the whole stern seemed to lift up as the motor synchronized at about 60 RPM, and then settled back down to normal speed. About then, I noticed that the first engineer left the HP extraction valve open. It was supposed to be closed when maneuvering. We were effectively bleeding back steam from the 75-psi auxiliary system into the turbine through a sticking check valve. As soon as the Chief closed the valve, everything settled back down.

On another occasion, we were entering port when I received a STOP bell. The ship still had way on, so the shaft kept rotating. The Master called down and demanded that I stop the shaft. I replied that the only way that I could do that was to start and synchronize the motor astern first. This would probably have thrown the stern off to port. He then started cursing at me and demanded to know if the Chief Engineer was down there. Naturally, he was not. Shortly afterwards, the Chief arrived and he asked me what the problem was. When I explained, his response was, “That guy doesn’t know what he is talking about, so don’t pay any attention to him”. He added, “If he screws up the landing it will be your fault and not his, so I will stay down here until we are tied up”. I was quite grateful.

On another occasion, I was getting ready to take over the watch in Port Arthur. The First Assistant met me at the top of the ladder and informed me that everything was normal down below. As I started down the ladder, I looked at the two Jerguson remote water level indicators mounted on the engine room bulkhead. The water level was all they way to the top in one glass and all the way to the bottom in the other one. I turned around, caught the First Assistant, and declined to relieve him until he straightened the situation out. I should point out that we never wrapped up a boiler on momentary high or low water on any tankers I served on. It was not uncommon to be the only engineer on board while in port. In the absence of an emergency diesel generator, I had no desire to attempt to relight fires in a boiler and raise steam by pumping diesel oil with a hand pump with only two people to help out.

During a transit of the Hudson River, the 0000-0400 fireman got into a dispute with the second and quit. I was pressed into temporary service as a fireman, even though I had only done it on the MMA school ship. I found it surprisingly easy. Unlike the U.S. Navy, the merchant service always assumed that you could do the job of any crewmember serving in a lower capacity, unless proven otherwise.

Another example of this occurred in Port Arthur one evening when the pump man did not show up in time to take on bunker fuel. So, I was asked to stand in for him. The operation looked fairly simple. There were only two bunker tanks. They were located immediately forward of the after deckhouse on the port and starboard side. The piping system was just a single header with port and starboard fill valves. The second mate helped me rig the hoses. I opened the ullage covers, determined the level in the tanks by peering down with my flashlight, and told the dock man to start pumping. The port tank started filling first, so I throttled back a bit on the fill valve. Shortly thereafter, I heard a noise that sounded like compressed air escaping. When it persisted, I turned around and discovered that it was not compressed air, but Bunker C fuel oil spraying into the harbor. A weld on the filling pipe had let go. The mate cursed a bit, threw some burlap bags on the spill, and then told me not to worry because this happened all the time. I doubted we would get away with it.

As we departed New York harbor, I went aft to secure the standby steering unit. This type of steering gear had no quick change over valves. The procedure was to open the bypass valve, close the line stop valves, and secure the motor. While I was on my way back to the engine room, an alarm bell went off in my head. I turned around and ran back to the steering gear. Sure enough, I had cut off the wrong motor. I quickly restarted the correct one. Fortunately, nobody had noticed. Interestingly, I have a copy of the National Transportation Safety Board Accident report of the collision of the bulk sulphur carrier SS Marine Floridian with the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge at Hopewell Virginia in 1977 due to a steering gear failure. The ship was a converted T-2 tanker with the same type of steering gear as the Texaco Minnesota and Texaco Washington.

We were scheduled to tie up in Bayonne, New Jersey, around 6 PM. I made a deal with the First Assistant that he would take my watches during this port stop while I took his in Port Arthur. My wife, brother in law, and his date were to pick me up at the pier. I was up on deck waiting to go ashore, when suddenly we swerved off to port just off Staten Island and dropped the anchor. We had to wait for the 0100 tide. I was quite upset, as there were no cell phones in those days. There was not much I could do. I went ahead and stood my regular watch. Then I changed into appropriate clothes to go ashore.

I knew I would have the maneuvering duty between 0000 and 0200. It normally involved was keeping the bell book while the second had the watch. Unfortunately, it did not work out that way. We had a new fireman who was having trouble keeping up with the maneuvers. The second decided to go out to the fire room and turn the controls over to me. What followed was one of the longest maneuvering watches I ever went through. The telegraph was dancing wildly all over the place. It took about an hour for us to get tied up. In the middle of all of this, the second came running out of the fire room, pointed up to the bridge, and yelled out, “Those people up there are crazy.” It was quite a workout. For much of it, I was the only person in the engine room. When I finally left the ship, my relatives were waiting patiently at the gate. My brother in law’s date must have thought we were all nuts. My wife’s first question was, “What were all those whistles out there.” I told her that it was impossible to explain.

The next misadventure occurred when we were leaving Boson Harbor. It was the oiler’s duty to go up and take a crew muster prior to getting underway. As we leftthe harbor, we suddenly went to anchor. I got a call from the bridge. I was asked if we had taken a muster and I replied in the affirmative. The question came back, “What about your Chief Engineer?” When I queried the oiler, he told me that all of the lights were out in the Chief’s cabin and assumed he was in there asleep. Since none of the rest of us had a chief’s license, it was illegal to sail. We had to anchor and wait for him in a boat. Both myself and the oiler met him at the gangway and apologized for the screw up. He said it was his own responsibility. When we arrived in our next port, he was promptly relieved and bounced back to second engineer on another ship.

Shortly after departure from one port, I happened to look up at the gage board and noted that the main steam line temperature had dropped from its normal reading of 740º to less than 500º. The boiler water levels were normal. I thought a bit and remembered that I had just secured the steam supply to the deck machinery. But I forgot to secure the feedwater supply to the line desuperheater. I de-superheated the entire main steam system. As soon as I secured the valve, the temperature returned to normal. Stupid me.

By now, Christmas was about to roll around. I decided that this was not how I was going to spend the rest of my life. I asked to be relieved in Portland, Maine, where my parents were living at the time. There was one last bite. My last watch was on the 0800 to 1200 while we discharged cargo. For some reason, we had to take a boiler off the line. In the middle of the watch, the steam pressure started dropping. I could see heavy black smoke coming out of the stack through the skylight. When I went out to the fire room, I discovered that the electrician decided to megger the forced draft blower motor. He was performing the operation on the boiler that was on the line. After I yelled over to him, he quickly restarted the blower and things returned to normal. Another bullet dodged.

This ends my account of my year in the merchant service. While a year does not sound like a very long time, it was a very eventful one. I think a few things that really helped make it so:

- Texaco put a fairly equal load on all three licensed engineers, rather than placing most of the responsibility on the first assistant. On a lot of merchant ships, the first assistant did all of the maneuvering.

- Gaining experience with three different plants.

- The fact that these were coastwise tankers that did a lot of maneuvering in restricted waters. This experience was not obtainable on ships engaged in open water voyages.

- Having to play MM, BT, MR, and EM, at some time or another.

- Being left on my own to figure out solutions to problems as they occurred.

Six months later, I was back in the Navy. I had another Chief Engineer’s tour on USS England (CG22) from 1967-70 and a tour on the CINCLANTFLT Propulsion Examining Board (PEB) from 1976-79. During that tour, I obtained a USCG Chief Engineer’s License. One of the things that concerned me during my tour on USS England was how little appreciation young sailors had for what they were operating. They saw things like 1200 psi boilers, 1000 psi return flow fuel oil systems, and Size 03 sprayer plates as normal. The senior petty officers of that era were not always experienced on these types of plants. The 1200 psi improvement program, PQS, and EOSS were yet to come. My biggest problem was probably keeping my hands off things. Sometimes it became necessary. The bottom line is that I was glad to have my merchant marine experience in later years. It got me through a lot of tricky situations.

Even though I was never on the bridge when entering or leaving port, I learned at least one lesson about ship handling during my time on tankers. Compared to my previous experiences on a destroyer, we went through some very wild maneuvering sessions, frequently with me on the throttles. In some ports, we received as many as 40 to 50 engine orders when maneuvering into a pier. FULL AHEAD to FULL ASTERN bells were not uncommon. I later realized these engine orders were necessary on a relatively large ship with a single screw and limited power in order to obtain adequate rudder action and it was possible to do this without building up much headway. About 20 years, later this came in very handy when I served as Commanding Officer of the destroyer tender USS Puget Sound (AD 38). We were entering the harbor in Barcelona, Spain when we had to make a sharp right turn to enter a narrow channel using full rudder. When the helmsman was told to steady up, he put the rudder hard left, but the ship’s bow kept going right. Just as it looked like we were going to run into a jetty I ordered “ENGINE AHEAD FLANK’ in order to get a good kick against the rudder. As soon as the bow started swinging back to port I issued the order “AHEAD 1/3”. The helmsman had no problem steadying up and we did not build up any appreciable headway. A valuable lesson learned.

By the 1990s, Texaco no longer operated a coastwise tanker fleet. These functions are now being carried out by integrated tug-barge assemblies.

Since the 1970s, there has been a major change over from steam to diesel power in the US Merchant Marine. Additionally, there is much more dependence on automation. Many ships are now being operated with unmanned engine rooms after reaching the sea buoy. This requires that they obtain the ABS certification ACCU. However, it is still important to make periodic rounds just as it was in the 1960s. If anything, more technical knowledge is required on the part of the ship engineers than in earlier days.

George W. Stewart is a retired US Navy Captain. He is a 1956 graduate of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. During his 30 year naval career, he held two ship commands and served a total of 8 years on naval material inspection boards, during which he conducted trials and inspections aboard over 200 naval vessels. Since his retirement from active naval service in 1986 he has been employed in the ship design industry where he has specialized in the development of concept designs of propulsion and powering systems, some of which have entered active service. He currently holds the title of Chief Marine Engineer at Marine Design Dynamics.

Fred Hoppe

Jerry Allen

Jennifer Ways