By Mark Huffman, RH Rositzke & Associates, LLC, Washington, DC (2013)

By Mark Huffman, RH Rositzke & Associates, LLC, Washington, DC (2013)

Reviewed by John R. Satterfield, DBA

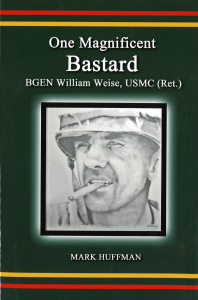

This brief volume tells the story of a distinguished Marine Corps veteran, BGen. William B. Weise, whose career spanned 1952 to 1982 and included service in Korea and Vietnam. BGen. Weise served with more than six months of combat commanding the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, in the Third Marine Division, stationed at South Vietnam’s east coast near the DMZ. 2/4 was configured as a battalion landing team (BLT) reinforced with tanks, an Ontos (an armored tracked vehicle with six 106mm recoilless rifles) platoon, AMPHTRACs, trucks, engineers, and recon and headquarters personnel. In heavy fighting before Weise assumed command, the battalion earned the nickname, “The Magnificent Bastards,” hence the biography’s title.

The defining moment of Weise’s command occurred over three days, April 30- May 3, 1968, in the Dai Do hamlet complex, between Dong Ha, the Third Marine Division’s headquarters, and the South China Sea. During this engagement, Weise’s battalion fought fang and claw with the North Vietnamese Army’s 320th Division to push enemy forces away from a position on a river bank that enabled them to attack shipping carrying vital supplies to Dong Ha. Weise, severely wounded, was evacuated near the battle’s end. During the fight 2/4 lost 81 KIA and 297 WIA, inflicting several times more NVA casualties throughout the assault, officially crediting the unit with 537 enemy dead, although the actual total may have been 1000 or more. The book states 397 WIA, but this may be a typographical error. 2/4’s monthly operational reports, readily available in online archives, show the lower number reported by Weise, and even fewer, 249, reported by higher command.

Whatever the number, it is clear that the battalion was mauled during the fight. Huffman reports about 625 Marines were involved, but this includes a “borrowed” company, B/1/3, which reinforced 2/4 early in the battle and took heavy losses as well. In fact, Weise’s command, stripped of its support units (assigned to other critical defense duties), consisted of four infantry companies with about 125 Marines available in each, far fewer than the standard Vietnam-era complement of 200. That means that, at the end of May 2nd when heavy fighting ended, 2/4’s four infantry companies were decimated. Company E had 45 men; Company F counted 52; Company G had 35; and Company H numbered 64. Casualties may have been even worse had the battalion been unable to call in support from artillery, naval gunfire, and Marine and USAF air attacks from nearby Dong Ha airfield. In fact, given the manpower disparity, it is likely that the Marines may have been overrun without this support and ceded control to the NVA of a strategically vital area that could have controlled a line of communication between offshore naval assets and Dong Ha.

This in no way diminishes the Marine’s achievement. Two of Weise’s company commanders received the Medal of Honor for their actions. Weise was awarded the Navy Cross, and many others were recognized for consistent gallantry against overwhelming odds.

Historians must, however, distinguish the purpose of this book, written as a well-deserved tribute to Weise, now 85, and designed to raise funds for the 2/4 memorial at the National Museum of the Marine Corps and similar projects at the museum and the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation.

Instead of dispassionate analysis of the decisions by various command levels that determined the flow of the Battle of Dai Do, the book contains many pages of endorsements and congratulatory messages to Weise from other distinguished high-ranking Marines. Of course all this is important and worthwhile, but anyone researching the battle will not find extensive and well-documented information to evaluate the action accurately and learn how to manage future engagements more efficiently.

The fact is, 2/4 ordered to push the enemy out of the area and retreated when promised support from a South Vietnamese Army unit on its left flank failed to appear. This left two weakened companies to face a larger enemy force. The entire battle was chaotic, with assaults against enemy emplacements that were much stronger than anticipated, frequently without coordinated fire support that may have caused excessive casualties during assaults. Commanders at several levels had little clear information about the nature and extent of enemy forces and defenses because commanders ordered immediate responses to NVA attacks without reconnaissance. Although the late military historian and Vietnam War specialist Keith Nolan covered the battle in his 2007 work The Magnificent Bastards, more research is welcome.

Furthermore, the biographical sections about Weise are, as one would expect in such a book, very positive, but they seem to gloss over his own misgivings about his role as a combat commander and the impact of the experience on his later life. This is obviously by design. This is a celebratory book, meant primarily to inspire. That is perfectly reasonable. Weise is a fine man, a capable leader, and a model Marine officer whom I would be delighted to meet and thank profusely for his outstanding service. Still, a more detailed account that covers every aspect of his career more honestly may be more valuable to scholars.

![]()

Dr. Satterfield teaches military history and served as a naval intelligence officer.

Robert Mercer

Tom McElreath