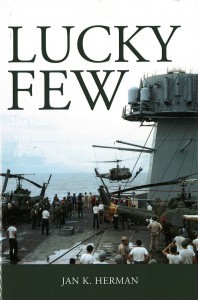

By Jan K. Herman, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD (2013)

By Jan K. Herman, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD (2013)

Reviewed by Nathan D. Wells

The role that the United States Navy played in the Vietnam Conflict is well known, especially with regard to the beginning and escalation of the conflict. The role played by the US Navy in the war’s final days is less known. The part played by the 7th Fleet Task Force in the rescue of thousands of refugees sheltered on board what was left of the Republic of Vietnam’s Navy is an epic one indeed. This task force and the Destroyer-Escort USS Kirk have both been overlooked for nearly four decades. That these stories have come to life is due to the efforts of historian and documentarian Jan K. Herman, who produced both a documentary as well and this fine volume.

A destroyer escort (now referred to as a frigate) such as USS Kirk might seem a strange protagonist for a rescue mission off Vietnam’s coast. Indeed, while these vessels (along with the larger Destroyers and Cruisers) performed yeoman service both protecting the fleet and in gunfire support for ground troops and junk forces. As the final North Vietnamese offensive rolled towards the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon in April 1975, Kirk and her sisters were helping evacuate the last American personnel from Cambodia. After a short 36-hour stopover in Singapore, they received orders to join Task Force 76 off South Vietnam. This force which included seventeen amphibious ships, two aircraft carriers, eleven replenishment ships and fourteen escorts (including the Kirk) that would attempt to rescue the remaining American personnel as well as South Vietnamese who would suffer reprisals.

The Navy deployed seventy-three ships in total for the operation. The initial plan had been to use fixed-wing aircraft out of Tan Son Nhut airbase, just north of Saigon. The base had quickly been compromised by advancing communist forces, and a helicopter evacuation was initiated. Kirk’s role was to provide surveillance, routine escort and patrol, naval gunfire support, and anti-air and anti-surface protection for the Task Force. With her flight deck, she could also serve as a temporary landing platform for any helicopters that did not have enough fuel to make it to one of the aircraft carriers or amphibious vessels. Because the escorts were closer to the shore than larger vessels, they quickly became a magnet for helicopters as the evacuation wore on, Having a small flight deck, most helicopters had to be pushed off into the sea; the skids doing quite a bit of damage to the deck itself. (On a more positive note, the aviation detachment would get a few “prizes”, including a brand-new UH-1 Huey that was the personal transport of a Vietnamese General.) The rescue of two Marine Corps helicopter pilots resulted in the Kirk being rewarded with five gallons of strawberry ice cream, per naval tradition.

Had this been the extent of Task Force 76 mission, this would have been merely another unsung laudable action in the annals of the US Navy. With the imminent fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the evacuation became something quite different. The Task Force set sail for Con Son Island; about 115 miles south of the Coast. The island that had been a penal colony during French colonial rule was now the last refuge for fifty Vietnamese ships and thousands of refugees. Herman introduces us to the crew of the Kirk, for the work tells their story. It is in this stage of the evacuation, from Con Son Island to the Philippines (where the ships would be turned over after a brief commissioning into the US Navy), that the crew comes to the forefront. The men of the Kirk had the utmost respect for their captain, LCDR Paul Jacobs. Even in advancing years, they speak of him with respect. Transforming a ship of war into a ship of hope is no easy thing; that Jacob could achieve such a feat was a credit to his own abilities, as well as those of his crew. The Kirk’s doctor, a Chief Hospitalman, served as a travelling country doctor to the motley flotilla; while enginemen helped keep most of the vessels afloat and underway. The deplorable conditions on many of these vessels were what one might expect from being overcrowded by desperate people from a nation that was soon to pass into history. Marines were assigned as security details. Several died, but most made it through safely due to the efforts of the Kirk and the Task Force as a whole. Many later immigrated to the United States and became citizens. Herman tells their stories as well.

This is a fine book overall. The major criticism that I have are that there are no maps, which would have been helpful to track the early stages of the evacuation. I recommend the volume to anyone interested in the US Navy’s role in Vietnam.

Nathan D. Wells is an Adjunct Professor of History at Quincy College, Quincy, Massachusetts.