Edited by Mark Tanner, Self Published, (2013)

Edited by Mark Tanner, Self Published, (2013)

Reviewed by Capt. Winn Price, USNR (Ret.)

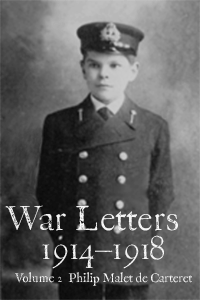

In 1911, 13 year-old Philip M. de Carteret received an appointment to the Royal Naval College in Osborne. His letters form the second of nine volumes, each compiling the letters of nine servicemen with two characteristics in common. All served during the First World War. None came home. No doubt each set of letters is poignant. I read letter after exuberant letter, sharing the fortunes and misfortunes of his early career. All the while, knowing that the letters would suddenly end brought a peculiar sadness and vague mourning 98 years after his death. Philip died aboard the battle cruiser H.M.S. Queen Mary amidst the Battle of Jutland.

Mark Tanner’s value-added is not the prose. That was provided by the century-old correspondence of a teenage naval cadet and his family. Rather, Tanner’s notes illuminate the letters, which might be less intelligible to us since we are not contemporaries of Philip de Carteret. We might be an American reader at risk of becoming cross-threaded by our common language.

Philip’s letters start in the fall of 1914 while he is serving on HMS Canopus, a pre-dreadnaught escorting two colliers to resupply RADM Cradock’s force off Chile. Before reaching the Royal Navy’s Pacific Station, the Germans under RADM Graf von Spee make short work of Monmouth and Good Hope in the disaster that was the Battle of Coronel, the opening World War I fleet action. “They were sunk with all hands. We were all frightfully sick at missing the action,” writes a naïve cadet to his father.

The letters follow his course from the Battle of the Falklands (1914) when Philip’s pre-dreadnaught is deliberately grounded in the harbor. Despite this, the ship still gets its first licks with her 12” battery. The next letters arrive home in Jersey with “postmarks” from Malta and the Dardanelles. Amidst the prolonged standoff at the straits, Philip writes his father that swim call often follows the inevitable game of deck hockey.

Nearly all of the cadet’s letters were addressed to his father or his brother Guy. No doubt this provided an intermediary censor as not to bring on an attack of vapors to the women folk. An exception to this was a 1915 Christmas letter to his grandmother. The letter unfortunately gave no indication that a war was underway. He opens the letter with a note of gratitude for her gift of one pound for Christmas, acknowledging that he will be challenged to spend it until his next visit to Malta.

In May of 1915, the campaign at the Dardanelles drew to a close. Canopus returned to England. After a period of leave, Philip joins the gunroom of HMS Queen Mary. In late May, he writes his last letter before Queen Mary left Roysth, Scotland, never to return.

The letters that form the core of this ebook are relatively few in number. Many of the letters from home undoubtedly went to rest on the bed of the North Sea.

War Letters 1914-1918, Vol. 2: P. Malet de Carteret offers the reader a series of verbal snapshots of gunroom life aboard two battleships from the perspective of a young man. If Philip lived, he might have become better known as a senior officer in the next conflagration at sea. Although it takes little time to read, it is easy to access on Amazon.com. During this centennial year, this work provides an extensive archive of WWI references for the professional who desires to pay tribute to those who fought the war to end all wars.

Winn Price has been researching the first Navy secret code developed in 1887 by Cdr. Hubbard and four newly commissioned classmates from ’85, including Ens. Coontz. The code permitted the navy to use Western Union for communications with shore bases and deployed ships visiting ports.