A Four-Part Blog Series

By Matthew T. Eng

Baseball in Norfolk radically changed the lives of the countless sailors stationed there during World War II. As a means of diversion, sailors at NTS Norfolk created their own private baseball utopia amidst the horrors of war waiting for them in the European and Pacific Theaters. Part three of the four part series.

PART III: The Beginning of a Rivalry

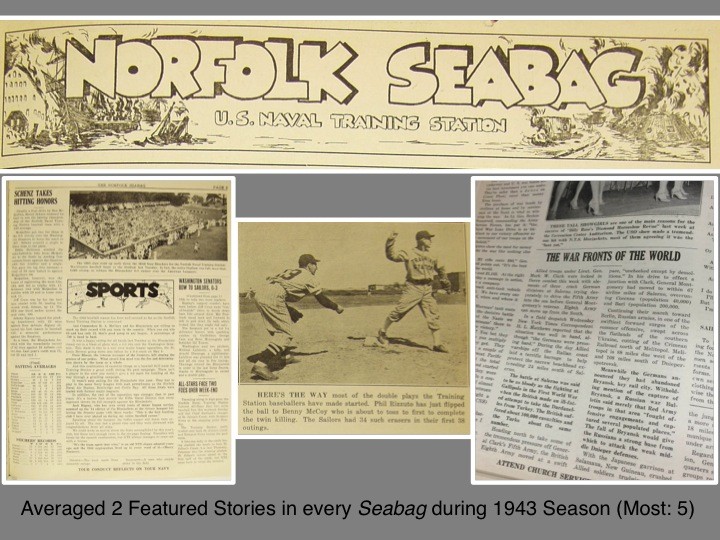

Naval Training Station Norfolk’s weekly wartime newspaper, the Norfolk Seabag, had a six-page, four-column spread. On average, each page contained four to five news items. The paper functioned to provide sailors with any and all information related to the functioning of one of the United States’ most powerful naval facilities. News snippets were also dedicated to the various goings-on around base. A sailor could read the latest updates on a weekend liberty pass or find out when next USO concert came to downtown Norfolk. Gossip and cartoons occupied a great deal of the paper’s back matter.

News from the outside world at war remained relatively minimal by comparison. Of the approximately thirty news snippets included in each Sea Bag issue, only a small two-column section (half a page) was devoted to war news. The “War Fronts the World” segment usually took stories from other newspaper feeds like the Boston Post, Associated Press, and Chicago Daily News. In 1943, the American public absorbed information on the impending Allied push into occupied Europe and the ongoing struggle with cracking the Japanese sphere of influence. For some, the “War Fronts the World” section was the only way they knew what was happening to their friends or family members forward deployed.

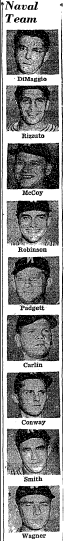

During the 1943 season between April and September, baseball stories appeared weekly. In some editions, information about the NTS Nine appeared five or six times. Stories highlighted star player bios with helpful tips for upcoming games. The base CO, Captain Henry McClure, took time out of his busy schedule to write to his sailors about the necessity for their continued support on and off the baseball diamond. Hearing about the Blue Jackets was inescapable. The paper even published each player’s ongoing season statistics. Sailors could keep track of their favorite players’ batting and earned run averages each week, just like they did at ball games before the war.

The majority of main articles were quick to point out each successive record-breaking attendance record at McClure field. It was as if the attendance was some invisible statistic everyone silently monitored for its prestige. Attendance rarely dipped below the 3,500-seat capacity. Analyzing each Sea Bag edition its content and subject matter would be another blog series in itself. That being said, Captain McClure kept his sailors in a tiny vacuum, with his namesake stadium as the center. King McClure had indeed carved out his kingdom.

Bats for Bonds

The season moved forward. The NTS Nine continued to win game after game against a slew of military and civilian opponents. Playing baseball outside of their commanding officer’s cocoon was a rarity, but it did occur. The NTS squad would also play the occasional war bond game. The bond games helped raise funds for the war effort while providing much needed entertainment and diversion from the horrors of war. Unfortunately, the United States government mandated the ration of gasoline. As a result, the NTS Blue Jackets never strayed far from their baseball utopia in Norfolk.

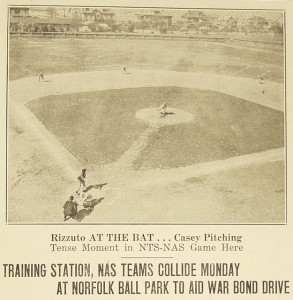

Although war bond drives were not a rarity in 1943, these games were. This was especially true for Hampton Roads audiences. One of the first bond games held in the area featured the area’s two best service teams, the NTS Nine and NAS squad. Led by players like Hugh Casey and Pee Wee Reese and coached by future Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, the NAS service team, occasionally referred to as the “Flyers,” was the most formidable foe to face the NTS Nine in their existence. Because of their similar celebrity status, they were also their most frequent foe.

The two teams squared off for a bond game on 26 April 1943 at nearby Norfolk Tar’s ballpark. Local media hailed it as an “All-Star” game of sorts. The Sea Bag called the prospective matchup “the most interesting series between two Service teams.” The price of admission for the game came in the form of U.S. War Bonds and stamps. War bond tickets ranged from the lower $1 bleachers and $3 grandstands to the deluxe $25 reserved seats near the field (The $25 seat equated to $18.75 in 1943 dollars). For Hampton Roads baseball fans, this was the closest they would get to see these stars without trekking to Washington, D.C. Residents jumped on the opportunity. Sea Bag reported the likelihood of “a goodly portion” of sailors “rooting for their respective favorites.” Tickets sold out well before the day of the game.

According to Norfolk historian Peggy Hail McPhillips, more than 4,000 fans attended the game. The sold out crowd helped generate close to $200,000 in bond money. NAS pitcher Hugh Casey stunned attendees with a no-hit, no-run shutout, beating the NTS Nine 4-0. Any doubt of a service rivalry before was quickly extinguished at the end of that game.

Bats Against the Nats

The greatest war bond game the NTS Nine played in happened one month later in Washington, D.C. The nation’s capitol hosted the “Washington Post Game” on 24 May to an expected sell out crowd of thousands. The hometown Washington Senators were set to square off against the famed Blue Jackets.

The impending excitement drew more press than anything else going on in Major League Baseball at the time. The Washington Post’s began a rigorous campaign began for the game. The paper ran at least one story about the game during that time period. Many articles made the front-page headlines. The post projected the game to be the largest “gate” in the history of baseball.

A total of 29,221 war bond buyers came to D.C.’s Griffith Stadium to watch the Nats play the Blue Jackets, falling short 4 to 3. The Nats had a hard time competing with the “best conditioned team” in the country. In all, the game raised nearly two million dollars under the moniker, “Baseball Fans Will Help Build a Battle Cruiser.” In attendance at the game was crooner Bing Crosby and Kate Smith, the “first lady of radio.” Both made appearances and sang to the beaming crowd of war supporters. The event was so successful that team owner Clark Griffith urged other teams around the country to do something similar to raise money.

A total of 29,221 war bond buyers came to D.C.’s Griffith Stadium to watch the Nats play the Blue Jackets, falling short 4 to 3. The Nats had a hard time competing with the “best conditioned team” in the country. In all, the game raised nearly two million dollars under the moniker, “Baseball Fans Will Help Build a Battle Cruiser.” In attendance at the game was crooner Bing Crosby and Kate Smith, the “first lady of radio.” Both made appearances and sang to the beaming crowd of war supporters. The event was so successful that team owner Clark Griffith urged other teams around the country to do something similar to raise money.

Rounding Third

The Blue Jackets turned heads and got the attention of newspapers around the country. That is, when news outlets got their hands on information about the team. You could see passing mention of them in brief snippets in major publications like the Washington Post and New York Times. They also made it to small papers such as the Ottawa Citizen and Lawrence Journal World. Because games were closed to the public, any information the public had about their favorite players was welcome.

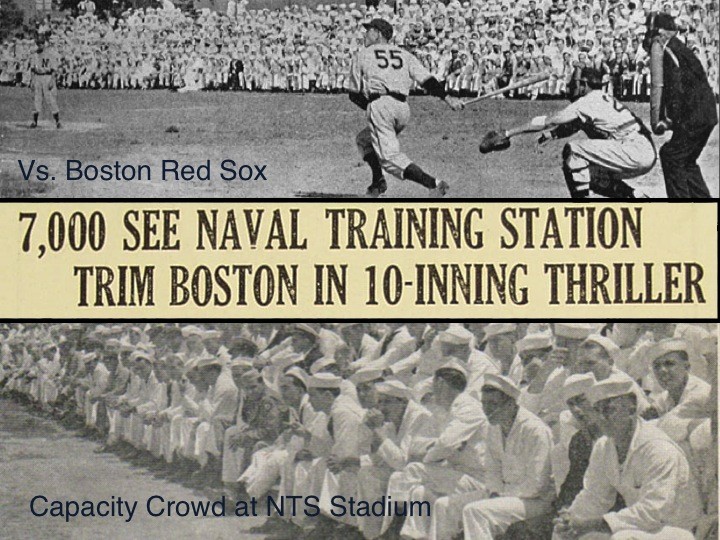

The team continued to perform better than expected. A NTS record 7,000 sailors came to see their beloved Blue Jackets beat the Boston Red Sox in a “10-inning thriller.” Over 15,000 attended their game against Ted Williams and the NC Pre-Flight Cloudbusters. The Blue Jackets won that game. They continued to play other professional teams like the St. Louis Browns (Baltimore Orioles) as the season progressed. Many teammates even felt were treated better than in the major leagues. According to a recent interview with first baseman Eddie Robinson, major league clubs couldn’t afford the kind of equipment that the Navy gave to their VIP sailors.

The NTS Nine consistently won games. In fact, the only team the Blue Jackets could not beat regularly was their rival, the NAS Flyers. The Blue Jackets ended their season only losing twenty-five games. Of those losses, nineteen came from the Flyers, the majority of which were attributed to Hugh Casey’s arm.

The two teams met a total of forty-four times during the season, with plans to draw it out for seven more in the 1943 Navy World Series scheduled for the middle of September.

Pingback: Discovering the Norfolk Naval Training Station Bluejackets Through Two Scarce Artifacts | Chevrons and Diamonds