Cracking Gibraltar is a blog series from the Naval Historical Foundation that will discuss the Army-Navy relationship involved in taking Fort Fisher, the last remaining Confederate stronghold in the Atlantic. READ PART I.

PART II: Butler’s “Singular and Interesting Disclosures”

Porter’s distaste for Butler was no secret. Political generals like Butler received regular harassment from career men like Porter. The disdain was clearly evident in Porter’s reports to both Grant and Welles in the weeks that followed the first attempt at Fort Fisher. He went so far as to suggest Butler quit the Army and return to civilian life. Admiral Porter often directed blame on others, when in reality some of the finger pointing should be directed his way.

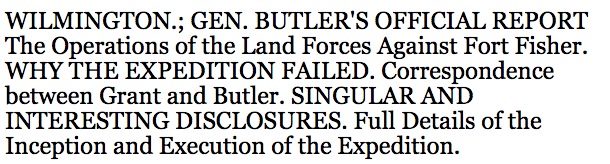

Despite his own personal distrust in the man, General Grant wanted Butler’s official report published. Butler’s 3 January official report contrasted to Porter’s official correspondence with Gideon Welles. The New York Times published the report on 14 January with this apologetic headline:

In his statement to General Grant, Butler swore that the naval bombardment did not damage the earthworks, even though his counterpart was “quite sanguine that he had silenced the guns” there. He cited historical precedent from the war about the Navy’s failure to silence the forts in New Orleans. Butler laid credibility to his argument based on the sole fact that he was there to witness both events. If it hadn’t worked before, why would anyone assume it would at Fort Fisher? Hindsight has a place in the annals of history:

“It is to be remarked that Admiral FARRAGUT even had never taken a fort, except by running by and cutting it off from all prospect of reinforcement, as Fort Jackson and Fort Morgan, and that no casemated fort had been silenced by a naval fire during the war; that if the Admiral would put his ships in the river the army could supply him across the beach, as we had proposed to do FARRAGUT at Fort St. Philip; that at least the blockade of Wilmington would be effectual even if we did not capture the fort.” (New York Times, January 14, 1865, 1)

The most damning information to Porter and the Navy was timing. According to Butler, the failure to take Fort Fisher was due in large part to the fleet’s sluggish movement to the rendezvous point off New Inlet prior to the attack. This troubled Butler, as he gave the Navy a “thirty six hours’ start” beginning on 14 December:

The most damning information to Porter and the Navy was timing. According to Butler, the failure to take Fort Fisher was due in large part to the fleet’s sluggish movement to the rendezvous point off New Inlet prior to the attack. This troubled Butler, as he gave the Navy a “thirty six hours’ start” beginning on 14 December:

“We there waited for the navy, Friday, the 16th, Saturday, the 17th, and Sunday, the 18th, during which days we had the finest possible weather and the smoothest sea.” (New York Times, January 14, 1865, 1)

Towards the end of the report, he reiterated his feelings toward the delay:

“The loss of Friday, Saturday and Sunday, the 16th, 17th and 18th of December, was the immediate cause of the failure of the expedition. It is not my province even to suggest blame to the navy for their delay of four days at Beauford. I know none of the reasons which do or do not justify it. It is presumed they are sufficient.” (New York Times, January 14, 1865, 1)

Neither Butler nor Porter could let it go. Days after the successful capture of Fort Fisher, and over a week after the New York Times published Butler’s report, Porter wrote a final scathing response to Secretary Welles. “Though the late results have completely refuted the assertions of Generals Butler and Weitzel” he wrote, “I deem it true to the naval part of the expedition that General Butler’s report should receive some notice at my hands.” The report is a lengthy five pages long and filled with the same venomous accusations he made in late December. Porter wanted to be clear and concise as to why Butler was (still) the wrong man for the job. He proceeded to go line by line, pointing out the faults in each statement:

“General Butler states that Admiral Porter was quite sanguine that he had -silenced the guns of Fort Fisher [. . .] That is a deliberate misstatement. General Butler does not say who urged me, but I never saw him or his staff after the landing on the beach, nor did I ever have any conversation with him, or see him (except on the deck of his vessel as I passed by in the flagship) from the time I left Fortress Monroe until he left here after his failure. He showed himself by that remark just as ignorant about hydrography as the rebel General Whiting did when he built his fort where he supposed large ships could not get near enough to attack it.”

The End of Butler

General Butler was relieved of his command of the Army of the James on 8 January 1865. That action was already in motion by end of 1864. General Grant wrote to Rear Admiral Porter from his headquarters at City Point on 30 December of his intentions to replace Butler with Major General Alfred H. Terry, a career officer both men could stand behind. Grant made every effort to convey the secrecy of the information he gave to Porter in light of the decision to promptly return back to Fort Fisher:

General Butler was relieved of his command of the Army of the James on 8 January 1865. That action was already in motion by end of 1864. General Grant wrote to Rear Admiral Porter from his headquarters at City Point on 30 December of his intentions to replace Butler with Major General Alfred H. Terry, a career officer both men could stand behind. Grant made every effort to convey the secrecy of the information he gave to Porter in light of the decision to promptly return back to Fort Fisher:

“I will endeavor to be back again with an increased force and without the former commander [. . .] There is not a soul here except my chief of staff, assistant adjutant-general, and myself knows of this intended renewal of our efforts against Wilmington [. . .] The commander of the expedition will probably be Major-General Terry. He will not know of it until he gets out to sea. He will go with sealed orders.” (Grant to Porter, ORN, Series I, Volume II, 394)

Butler went to Washington to answer to the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of War at his request. He once again insisted to the committee that Fort Fisher was heavily armed and guarded by Confederates, proving his decision to abort the mission was justified.

His efforts proved fruitless. His replacement effectively ended Butler’s military career less than one week later. General Butler went to New York after the embarrassing debacle down South until the end of the war. He retired from military life to once again pursue his political endeavors in Massachusetts. He went on to achieve the fame and success he so greatly desired during the war, serving as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and the state’s 33rd governor. He died in 1893 in Washington, DC.

Coming Soon: Part III: Preparing for Attack

Pingback: Cracking Gibraltar: The Union Takes Fort Fisher (PART III) | Naval Historical Foundation