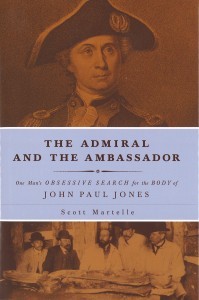

By Scott Martelle, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL (2014)

By Scott Martelle, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL (2014)

Reviewed by John R. Satterfield, DBA

The Continental Navy had negligible impact on the American Revolution’s outcome. Its handful of little ships served almost entirely as commerce raiders, attacking and capturing defenseless merchantmen and occasionally engaging with small British warships of comparable or lesser capability. The Revolution was a training ground for many leaders of the early United States Navy, re-established in 1794 to counter the threat of Mediterranean pirates to American maritime commerce. The most notable Continental Navy commander during the Revolution was not, however, among the men who founded the new nation’s naval culture and ethos. Captain John Paul Jones was buried in a small Protestant cemetery on the outskirts of 18th-century Paris, dead from kidney disease at age 45 in 1792.

Although Jones’ life is well documented and needs no recounting, this volume deals extensively with his remarkable wartime achievements and his memorably irascible and arrogant personality that led in major part to his slide into obscurity after the Revolutionary War. According to author Martelle, a writer for the Los Angeles Times, Jones might never have become the “Father of the American Navy” with a celebrated tomb and shrine at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis had it not been for an improbable confluence of events at the turn of the 20th century and the guiding hand of the U.S. Ambassador to France, Horace Porter.

Porter was an unlikely candidate for Jones’ resurrection. A West Point graduate, Civil War hero and protégé of Ulysses S. Grant, Porter won appointment as the U.S. ambassador to France after William McKinley’s election as president. Significantly, Porter had led a successful campaign to raise funds for Grant’s Tomb in New York City in 1897. He left for Paris within days of the monument’s dedication and remained there until 1905.

During Porter’s long tenure in Paris, overwhelming American naval victories in the Spanish-American War awakened broad public interest in the nation’s naval and military heritage. Questions arose in Congress and elsewhere about John Paul Jones’ seemingly inappropriate burial in foreign soil. Inquiries, however, found no evidence of his final resting place. In fact, the cemetery where he was interred had been abandoned and covered over within a decade or so of his death. Many historians believed that his remains were gone, dug up and discarded when new development in the expanding city led to removal of many ancient graveyards.

Porter brought far more to the search for Jones than others, however, including the authority of the U.S. government and its friendship with France, personal wealth that funded the research and effort to locate the grave, and careful, meticulous management of competent assistants.

Archival research finally revealed St. Louis Cemetery, long since buried deep under a block of commercial buildings in a lower-class area of northeast Paris. Porter arranged for vertical shafts to be sunk on the property and in adjacent streets. Nearly 20 feet below the surface, excavators dug out tunnels, supporting them with timbers to prevent cave-ins. Workers undoubtedly thought they had entered the gates of hell, unearthing layers of skeletons human and animal and enormous red earthworms that had thrived underground.

Fortunately, records indicated that friends had placed Jones in a lead coffin filled with alcohol to preserve his body for eventual exhumation. This forethought focused Porter’s search. Several lead coffins were unearthed, but only one was promising. When it was opened, the body inside was remarkably preserved, and all the elements noted in contemporary accounts of Jones’ burial matched. An autopsy of the corpse confirmed the cause of death diagnosed by Jones’ physician, and precise measurements of his body and head matched the famous bust of Jones by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, considered by everyone to be a remarkably accurate likeness.

Jones came back to America amid pomp and circumstance. President Theodore Roosevelt presided over a ceremony at Annapolis in the spring of 1906, but the Naval Academy Chapel and the crypt for Jones were not completed until 1913. With little fanfare, Jones’ body was transferred from under the main staircase in Bancroft Hall, the Academy’s dormitory, into the Grand Antique de Pyrenees marble sarcophagus supported by dolphins cresting the waves where he rests today.

Porter, obviously a remarkable man in his own right, lived until 1921 and lies buried in obscurity in West Long Branch, New Jersey, once the site of his summer home. (He is currently resting at Arlington National Cemetery)

Martelle tells a worthwhile tale, but his book, although brief, would have benefitted from more stringent editing. It’s hard at times to tell exactly where the story leads, as it contains numerous forays into history that have little or nothing to do with the primary topic, the search for Jones. These tangents can be interesting and add texture to the era covered in the book, but they also divert attention from and offer little explanation for the odd connection between an old Civil War artilleryman and the rough, even older sea captain he dug out of the ground.

Dr. Satterfield has written two books on World War II naval history, many of articles on naval weapon systems and teaches military and naval history.

Pingback: When John Paul Jones crossed over – MilitaryQ