It’s a question that Naval Historical Foundation historian Dave Winkler addresses in his recently published book, Ready Then, Ready Now, Ready Always: A Centennial of Service by Citizen Sailors. In the book’s opening chapter, he notes that President Thomas Jefferson foresaw the need for a personnel augmentation contingency and proposed the Naval Militia Act of 1805. However, Congress balked at the idea of establishing and paying for naval militias at a time when there was an excess capacity of trained merchantmen within the dominant American maritime industry.

It’s a question that Naval Historical Foundation historian Dave Winkler addresses in his recently published book, Ready Then, Ready Now, Ready Always: A Centennial of Service by Citizen Sailors. In the book’s opening chapter, he notes that President Thomas Jefferson foresaw the need for a personnel augmentation contingency and proposed the Naval Militia Act of 1805. However, Congress balked at the idea of establishing and paying for naval militias at a time when there was an excess capacity of trained merchantmen within the dominant American maritime industry.

In the short term, the Navy had more than enough trained men to draw upon during the War of 1812 and the war against Mexico in 1845. During the War of 1812, American privateers operating on the high seas served as an effective force multiplier. In the long term, the Navy ran into difficulties in finding Sailors to crew its rapidly expanding fleet during the American Civil War. The Navy had to compete with the Army, which had the benefit of the Militia Act of 1792 in existence to obtain white males between the ages of 18 and 45. That the Navy did meet its manpower needs can be thanked, in part, to the racial component of the Militia Act. The Navy drew on African-Americans, many being recently freed Slaves, to fill out its crews. Some twenty percent of the Navy’s Sailors during the Civil War were black – that was double the percentage of African Americans who served in the Union Army.

Following the Civil War, the decline of the merchant marine also meant the number of merchant mariners available for naval service was also in a tailspin. As the Navy grew more technologically sophisticated, the skill sets needed to operate merchant vessels and warships were no longer interchangeable.

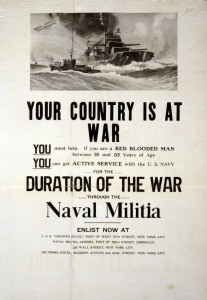

With Naval Attaches assigned to European capitals reporting on the creation and implementation of naval reserves in the various European navies, serious discussions began in the late 1880s on what shape an American naval reserve might take. When legislation to establish a federal naval reserve force failed in Congress, local leaders, starting in Massachusetts and New York, created Naval Militia units. (Today New York still has a naval militia!). The number of Naval Militias grew in size during the 1890s, with units forming mostly in states that fronted a major body of water.

During the Spanish-American War, Naval Militias performed coastal defense roles, manning up several Civil-War era monitors to provide harbor protection, Naval Militias from Michigan, Maryland, New York, and Massachusetts also provided crews for four auxiliary cruisers that were acquired to support fleet operations off Cuba. While the four cruisers accounted well for themselves, the bureaucratic hoops involved in having the militiamen resign from their respective state militias in order to come into federal service was an experience the Navy did not care to repeat. Thus at the turn of the century, legislation was repeatedly submitted to create a naval reserve only to stall during an era following the annexation of the Philippines where there were strong anti-imperialists sentiments on Capitol Hill.

Finally, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, with the backdrop of the outbreak of war in Europe, was able to have language inserted into an omnibus bill that also created the office of the Chief of Naval Operations, that would enable the Navy to recruit Sailors coming off of active duty into a manpower that we now call the Navy Reserve.

Winkler’s book then details the history of the Navy Reserve starting from World War I through the present, highlighting the role the component as serve as an agent of social change to enable women and minorities an opportunity to serve the nation. The book can be obtained by going to the website HERE.