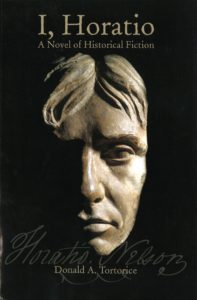

By Donald A. Tortorice, Author House, Bloomington, IN (2014)

By Donald A. Tortorice, Author House, Bloomington, IN (2014)

Reviewed by John R. Satterfield, DBA

I, Horatio is a fictional autobiography about Horatio Nelson, clearly a subject of note for those who care about naval history.

Nelson’s titles were read out loud to an assemblage of mourners at his funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London after his death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This litany reflects his heroic status and naval achievements, as well as his legendary vanity and self-absorption:

“The Most Noble Lord Horatio Nelson, Viscount and Baron Nelson, of the Nile and of Burnham Thorpe in the County of Norfolk, Baron Nelson of the Nile and of Hilborough in the said County, Knight of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Vice Admiral of the White Squadron of the Fleet, Commander in Chief of his Majesty’s Ships and Vessels in the Mediterranean, Duke of Bronté in the Kingdom of Sicily, Knight Grand Cross of the Sicilian Order of St Ferdinand and of Merit, Member of the Ottoman Order of the Crescent, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of St Joachim.”

1st Viscount Nelson’s unquestionably epic status as a naval leader mixes with his equally epic character flaws, most notably in his abandonment of his wife Frances for the euphemistically described courtesan Emma Hamilton, herself the mistress and later wife of Sir William Hamilton, British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy and Britain’s government tolerated Nelson’s personal failings and scandals because his tactical skills, leadership abilities, imagination and initiative. His participation in naval battles like Cape St. Vincent (1797), the Nile (1798), Copenhagen (1801) and Trafalgar (1805) were instrumental in defeating Napoleon Bonaparte’s aspirations for European dominance. This complex, controversial and ambivalent character is the stuff of great biography. More than 100 works have appeared since the first official volume in 1809, with renewed interest and new books from the bicentennial of Trafalgar in 2005.

Author Donald Tortorice, a retired attorney, law professor, and former Vietnam War swift boat commander, has commendably attempted to take a new look at Nelson by producing a historical novel written in the first person.

Unfortunately, the attempt failed for this reviewer. Mr. Tortorice undoubtedly knows his subject, having studied and drawn inspiration from Nelson throughout his life. A successful faux autobiography cannot work, however, unless the reader suspends disbelief. The French call this dramatic attribute vraisemblance. When this narrative, attributable to Nelson, begins with his own assessment of his impact on British history after his death (something he could not possibly have known), vraisemblance vanishes and never returns. In fairness, speaking in first person is extraordinarily difficult, even more so when the writer must channel the mind of another dead for more than 200 years. Presentism and hindsight almost inevitably creep into the monologue throughout this volume. For example, Nelson’s voice often refers to Marines embarked on ships under his command using rifles when the Sea Service Brown Bess .75-caliber musket was the standard British naval firearm from the American Revolution until the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars.

More importantly, the story involves little in the way of interior thinking that should be in the moment in all cases. It focuses instead on largely hindsight views of activities observed and documented by others, as well as in Nelson’s own correspondence, used liberally throughout the book as if it were contemporaneous conversation rather than historical record. One would expect, of course, for Nelson to think of himself in positive terms, but there is almost no expression of self-doubt, connivance or duplicity. These are modes of behavior that all of us practice and at least occasionally acknowledge in moments of honest reflection. Consequently, Nelson as the novel protagonist seems mechanically formal and distant from his surroundings, even when describing frequent sexual encounters with women throughout his life, a topic rarely addressed explicitly in biographical works.

Despite the author’s obvious devotion to Nelson, I would recommend this book only to readers whose aversion to substantive historical narratives would overcome their interest in learning about Nelson’s life. Good relatively recent biographies (averaging about 800 pages each) include Roger Knight’s The Pursuit of Victory (2006): the two-volume work by John Sugden Nelson: A Dream of Glory, 1758-1797 (2004) and Nelson: The Sword of Albion (2013): and Nelson (1996) by Carola Oman. Nelson’s correspondence is available in multiple volumes, and analyses of his career in command are also numerous. A particularly good one, used at the Naval War College when this writer completed the course, is Captain Geoffrey Bennett, RN (Ret.)’s Nelson the Commander (1972, repr. 2005).

Dr. Satterfield teaches and writes about military and naval history. He is a member of the Nelson Society and the 1805 Club.