By David F. Winkler, Ph.D.

NHF Staff

The video of a Russian Sukhoi SU-24 attack jet making close passes near the destroyer USS Donald Cook on April 12 in the Baltic brought back recollections from the early Cold War when such bravado demonstrations were frequently conducted by the naval air forces of both super power protagonists.

USS Essex (CVS-9) underway, circa 1967. (Image courtesy NAVSOURCE)

Essex’s rescue helicopter, already airborne as a safety measure during flight operations, rushed to the scene of the crash and found no survivors. Small boats were placed in the water to recover debris and human remains. Concerned that the crash could be interpreted as a shoot down, flash message traffic was sent to Washington to explain the circumstances to pass along to Soviet authorities. At sea some 100 miles from the crash site, the destroyer Warrington flagged down a Soviet destroyer to pass along the same message. That destroyer immediately proceeded to the vicinity of the Essex.

As the Soviet warship arrived and took station astern, the operations officer, Commander Edward Day was given the solemn task of transporting by small boat, the aircrew remains to the Soviet warship. As the boat made its way aft, S-2 Trackers flew the missing man formation overhead to pay homage to the lost Soviet aviators. The Soviet destroyer rendered honors with a gun salute.

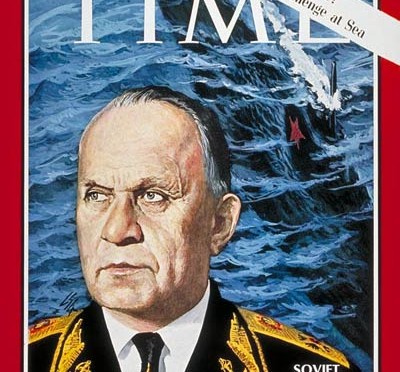

A month earlier, following a continuing series of incidents at sea such as the one discussed above, the United States had approached the Soviets on safety at sea talks. Finally, after a Soviet destroyer collided with the HMS Ark Royal on November 9, 1970, the Soviets agreed to discuss negotiating an accord that would modify the behaviors of their respective naval forces. Signed on May 25th, 1972, by Secretary of the Navy John W. Warner and Admiral of the Fleet, Sergei Gorshkov on behalf of their presidents, the Incidents at Sea Agreement ended the days of Cowboys and Cossacks on the high seas.

One of the turning points during the negotiations came during the discussions on aviation operations where the negotiators seemed to be talking past each other. The American negotiator, Captain Edward Day decided to relate his experience of May 25, 1968 to his counterpart, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Naval Aviation General Major Nikolai I. Vishensky. Day concluded that the purpose of their talks was to prevent such needless tragedies in the future. Vishensky became emotional. He then informed Day that the body he returned was that of his son. From then on the two men talked to each other and achieved the necessary progress to complete an agreement that remains in effect today.

One difference between today and the Cold War era is social media. During the Cold War such low overflights would be filmed and discussed at the annual review sessions out of view of the media and the political establishment. Today, such incidents can be transmitted via social media by some crewmember or embarked reporter with a smart phone and find there way into the 24 hour news cycle. Unfortunately, the short term frenzy created by such exposure could have a corrosive effect on long-term behavior regimes.

For sure, the overflights will be discussed at the next annual gathering of senior naval officers from the United States and Russia. If the pattern from past talks continues, those discussions will be frank with mistakes admitted. Furthermore, those deliberations will be kept in private. During duty with “OPNAV” Staff I once came across a stamp the read: FOR US-USSR EYES ONLY. I would not be surprised if today it has been replaced with a FOR US-RUSSIA EYES ONLY stamp.

Dr. Winkler wrote his dissertation on the Incident at Sea Agreement that was published by the Naval Institute Press in 2000 as Cold War at Sea.

capt l b Brennan USN ret

William G Schultz

William G Schultz

Forrest M. Pirovano