Blood, Bravery, and Intrepid Ships is a new limited, 5-part blog series exploring 5 epic naval battles throughout the history of the United States Navy.

DISCLAIMER: This post is related to the 6th Season, 9th episode of the HBO series Game of Thrones titled “Battle of the Bastards.” Although the historical content of the five naval battles included are accurate, its ties to the HBO series remain wholly fictional. [SPOILERS AHEAD] Read a recap of the episode at EW.

The views and opinions represented in this post are personal and belong solely to the author. They do not necessarily represent those of the Naval Historical Foundation, Naval History and Heritage Command, or United States Navy, unless explicitly stated. If you have any questions, please contact our Digital Content Developer, Matthew Eng, at meng@navyhistory.org.

By Matthew T. Eng

If you have perused social media within the last week, you are likely aware that television history was made Sunday night. The wildly popular HBO television series Game of Thrones aired their episode “Battle of the Bastards” to over 7.66 million anxious and excited viewers. It was an epic showdown between the armies of Jon Snow and Ramsay Bolton for supremacy of the North. Amidst all the chaos, Jon Snow and House Stark prove triumphant, once again displaying the banner of the dire wolf at Winterfell.

Raising the Flag (USN 902736)

Surely. Ready a raven, Lord Snow. You might want to write this down and let the others in the seven kingdoms know.

Real life battles are spontaneous and chaotic, but no less epic. Indeed, history is never so nice and neat to be wrapped up in a one-hour episode. Sets are battlefields, directors are commanders, and eyewitnesses give us the only glimpse into a camera’s eye view of the events that transpired. Battles rage on, casualties rise, and victories are made at a high cost. Our collective knowledge tells us that knock-down, drag out fights have occurred throughout the history of the United States so wars could be won and the freedom and protection of the United States secured. In a figurative sense, the men and women of the United States military have made sure that the banners of our great nation remain intact. The United States Navy plays a key role in that narrative – no extras or stuntmen required.

Here are five epic engagements that give “Battle of the Bastards” a run for its money.

PART I: The Battle of Lake Erie: Symbolism Matters (September 10, 1813)

Symbols have an important place in U.S. naval lore. Ask any sailor, and they will name a few. The anchor and chains. The dolphin. Wings of gold. Every sailor, both officer and enlisted, wears a symbol to denote their rank and/or rating.

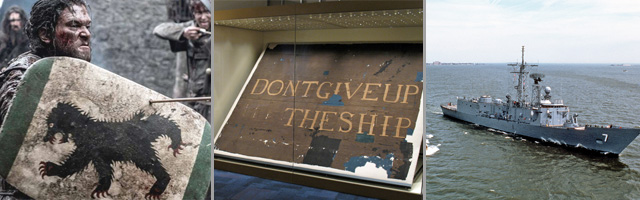

These symbols are worn as a sign of pride and a marker displaying allegiance. After all, why does every ship in the U.S. Navy today have a seal or crest? Are things so different in the world of Game of Thrones? Bloggers and critics worldwide are still debating the symbolism of Jon Snow’s use of the House Mormont shield to deflect his enemy’s expertly aimed arrows in the most recent episode of Game of Thrones. The shield has meaning, just as medals do to sailors. These symbols become much more than painted images on flags, shields, and steel. Their imagery also helps boost the morale and fighting spirit of combatants during battle. This was the case during the Battle of Lake Erie when a young and daring commander named Oliver Hazard Perry used five words to rally his rag tag group of sailors and volunteers to the Navy’s most decisive victory during the War of 1812: Don’t Give Up the Ship. Like a sigil on a shield, “Don’t Give Up the Ship” became a powerful message the U.S. Navy adopted and continues to use today.

Marmont Shield used by Snow in “Battle of the Bastards” (HBO); “Don’t Give Up the Ship Flag (Photo courtesy New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and

Historic Preservation), Oliver Hazard Perry Class Frigate (Wikimedia Commons/Navy.mil)

Perry’s British adversary on Lake Erie, Commander Robert Heriot Barclay, was no Ramsay Bolton. A battle seasoned naval officer who cut his teeth at the Battle of Trafalgar during the Napoleonic Wars, Barclay took command of a detached squadron of British ships on Lake Erie. During the beginning of the summer, Perry and Barclay sat at their bases of operation on the lake, calculating the best time to strike. Procuring ships to fight, however, proved no easy task. If there ever was an early version of an arms race in the young Republic, it first occurred along Lake Erie during the War of 1812. Perry and the Navy set about building ships and procuring men and materials to help protect his base of operations at Presque Isle shipyard. By the middle of the summer, Perry’s shipbuilding plan seemed to work. He built a fleet of two brigs, three gunboats, and a pilot boat that outnumbered the British fleet. There was only one problem: manpower. Added to the stress and confusion for Perry was the news that his good friend James Lawrence, commanding officer of USS Chesapeake, was killed in an engagement with HMS Shannon near Boston. Perry used his friends dying words “Don’t Give Up the Ship” as motivation to press on, eventually using it as his personal battle flag made for him. As an added honor, he named one of the brigs built as his flagship after his friend, Lawrence. On the other side of the water, Barclay took the opportunity to continue to blockade Perry in at Presque Isle at the end of July.

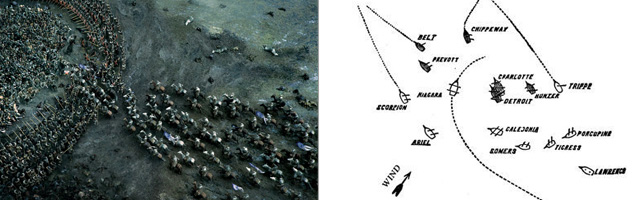

Eventually, the blockade was abandoned, allowing Perry and his ships to escape. Soon, men and materiel from the east, along with a small continent of Major General Harrison’s Army of the Northwest, swelled Perry’s meager ranks at Put-in-Bay, Ohio. Barclay, now unable to move at Amherstburg, had little choice but to meet Perry’s makeshift in battle.

Painting by William H. Powell, depicting Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry transferring his flag from the disabled U.S. Brig Lawrence to the U.S. Brig Niagara, at the height of the action. (NHHC Photo $# KN-621)

“The loss of the Americans was severe, particular on board the Lawrence. When her flag was struck she had but nine men fit for duty remaining on her deck [. . .] Her deck, the morning after the conflict [. . .] exhibited a scene that defies description- for it was literally covered with blood, which still adhered to the plank in clots – brains, hair and fragments of bones were still sticking to the rigging and sides.”

Naval surgeon Parsons described an equally harrowing scene in his discourse delivered before the Rhode Island Historical Society:

“In proper time however as it proved, the dogs of war were let loose from their leash, and it seemed as though heaven and earth were at logger-heads. For more than two long hours, little could be heard but the deafening thunders of our own broad-sides, the crash of balls dashing through our timbers, and the shrieks of the wounded.”

With four fifths of his crew either killed or wounded, Perry decided to transfer his flag to Niagara, flag in tow, gallantly rowing through heavy gunfire while Lawrence was surrendered. Although the American fleet was battered, their British counterparts didn’t fare any better. Both Detroit and Queen Charlotte were badly damage from the battle, with most of their crews killed or wounded. Barclay himself was wounded from the engagement.

A break in the line for Perry at Lake Erie (HBO/Naval History Heritage Command)

Dear General:

We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one school and one sloop.

Americans controlled Lake Erie for the remainder of the war. What will Jon Snow’s success mean for the future of Winterfell?

Pingback: Blood, Bravery, and Intrepid Ships: 5 Epic Naval Battles (PART II) | Naval Historical Foundation