CHOW is a new blog and video series exploring the history behind U.S. Navy culinary traditions. Read the first two entries here: S.O.S. and Navy Bean Soup.

CHOW is a new blog and video series exploring the history behind U.S. Navy culinary traditions. Read the first two entries here: S.O.S. and Navy Bean Soup.

By Matthew T. Eng

Well, it is officially summer. If the spiking temperatures and humidity here in the nation’s capital do not tell you what time of year it is, the abundance of mosquitos buzzing around your backyard barbeques will. If you are like me, you enjoy the refreshing taste and sharp bite of a cold and stiff drink on a hot summer’s day in the sun. In honor of summer, this next edition of CHOW will feature a classic summertime cocktail introduced into the United States by a naval office at the turn-of-the-century.

I think drinks are best served with a little bit of naval history. Here is the story behind the daiquiri.

A Simple Drink of Lemon or ‘limón: A Complicated Recipe

The daiquiri is not a complicated drink. Take a shaker of ice, fill it with blanco rum, some sour juice, a dash of sugar, and mix it. Serve chilled. Easy, right? That is apparently wrong. There is much more to this Cuban export than meets the eye, and the Navy plays a key role in its development.

The combination of rum, sugar, and lime juice was a well-known elixir of choice throughout the Caribbean in the 16th and 17th centuries. The concept of mixing fruit juice with rum is not lost on any naval enthusiast, either. During the 18th century, Royal Navy Admiral Edward Vernon ordered the daily rum ration be diluted with water and lime. This order served two purposes: British sailors would be soberer and abler to fight off scurvy with a hefty daily dose of citrus.

Fast forward to 1898. Spanish American War. Cuba.

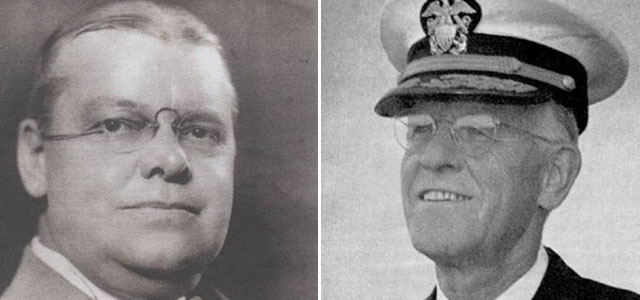

The origin story of the original recipe is as murky as the drink’s consistency. There are countless websites, blogs, and articles that detail their version of the recipe, all of which claim to be the “most accurate to the original.” The drink is not complicated because it’s creator, Jennings Cox, had little materials to make a fancy drink.

Legend has it that Jennings Cox, an American iron miner who came to the island in the wake of the American victory, was planning to entertain guests one night, only to realize he ran out of gin. With limited materials at hand, he bought a common island liquor (rum) to mix together with citrus juice, sugar, and a little bit of water. After mixing it, he poured it together with ice to make as a punch for his guests. His guests instantly loved it, and its popularity grew on the island.

Stories continue to surround exactly how he came up with the name “daiquiri.” The easiest explanation was that he named it after the town of Daiquiri where his mine was located east of Santiago de Cuba. Another story from the 14 March 1937 edition of the Miami Herald reposted by the blog “To have and Have Another” details a much more spontaneous origin:

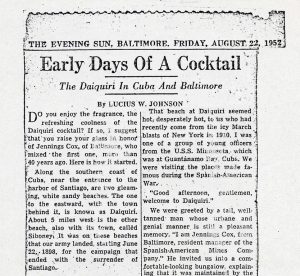

Whatever story you believe, the drink eventually made it into the hands of a junior medical officer, Lucius W. Johnson, in 1909. Johnson and the crew of USS Minnesota were in Cuba touring the battlefields from the Spanish American War. The future Rear Admiral was introduced to Cox during a tour of the island’s battlegrounds. Cox was quick to introduce him to his favorite drink; which Johnson instantly fell in love with the refreshing drink. He explained his first encounter with Cox in detail in a 22 August 1952 edition of the Baltimore Evening Sun:“One day a group of American engineers who had come into town from the Daiquiri mines were imbibing their favorite drink in this restful spot. It was one of those wonderful rum concoctions made from Ron Bacardi. A jovial fellow by the name of Cox spoke up. ‘Caballeros y amigos, we have been enjoying this delicious mixture for some time, but strange to admit the drink has no name. Don’t you think it is about time something was done to extricate us from this sad predicament?’ It was unanimously agreed that the drink should be named, without further procrastination.

There was silence for several minutes as each man became immersed in deep thought. Suddenly, Cox’s voice was heard again. ‘I have it, men! Let’s call it the “Daiquiri!”’ And so it was christened.”

“We were greeted by a tall, well-tanned man whose urbane and genial manner is still a pleasant memory [. . .] When we were pleasantly relaxed he prepared for us a drink which brought quick relief to our arid throats. He had put it together, he told us, to make the locally produced rum more agreeable to foreign taste. It had been christened Daiquiri in honor of its birthplace.

Johnson was smart enough to know the drink had a future beyond the Cuban coastline. He brought several gallon jugs of rum home with him and introduced the drink to the Army and Navy Club in downtown Washington, D.C., which “scored an immediate success.” In fact, the Club staked its reputation on the cocktail throughout the early to mid-twentieth century. In 1984, the Club’s manager humorously remarked on the history of the drink in the New York Times, stating that they “feature it, but these guys will drink anything.”

The drink was later introduced to the University Club in Baltimore and Army and Navy Club in San Francisco. From San Francisco, the drink made it to Honolulu, Guam, and Manila. The regional specialty from Jennings Cox was a global phenomenon in the Prohibition era. By then, additions to Johnson’s specifications brought over stateside had already made it a different drink altogether (i.e. the Ernest Hemingway version). The water was removed from the mix, and additional elements like bitters and sweet liquors were introduced. The daiquiri we know in contemporary America today is a bastardization of the original, often served as a frozen drink with more sugar and less alcohol. Any good British sailor of the 18th century would be rolling in their graves.

And then there is the issue of the recipe itself. Most scholarly and secondary source research into the drink’s origins put it as a simple recipe that includes rum, ice, sugar, and lime juice. The concoction is then shaken together and served in a chilled or frosted glass. The drink is traditionally served this way at the Army Navy Club in its aptly-named Daiquiri Room bar. Lucius Johnson corroborated this recipe in a brief article that appeared in the Baltimore Evening Sun article:

“Over cracked ice he poured two jiggers of rum, then added a level teaspoonful of sugar. Next he squeezed into each glass the juice of a lime, being careful to include some of the oil from the skin. The mixture was stirred gently and, in that humid climate, the cold glass quickly became frosted.”

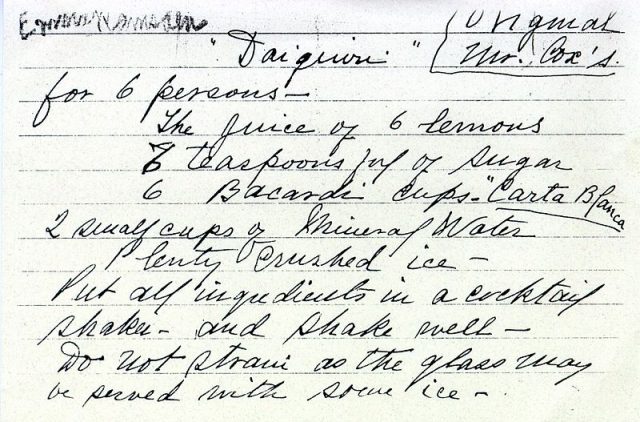

Variations, however, exist. Through the research into the culinary history of the cocktail, the “original” Jennings Cox recipe for the daiquiri in special collections at the University of Miami library used the juice of a lemon, not a lime.

This is unfortunately one of the only places to include this distinction. Despite the recipe card from Cox, online tutorials still use lime juice instead of lemon. The popular rum blog “The Rum Nerd” explains why the recipe card may be in error:

“One thing to note is that Cox says to use lemons, however as limes are abundant on Cuba and are commonly referred to as ” ‘limón” it’s probable he was referring to limes. The recipe as written is similar to that for Grog, the drink used to serve the daily rum ration to sailors of the Royal Navy, so adding lime and sugar to rum is hardly a great leap of logic.”

The Recipe

I wrestled over which citrus fruit to include. Lemon or lime? In the end, I decided to remain faithful to the recipe card and use a lemon. If you prefer to use lime as the “traditional” recipe, that is your prerogative. The following recipe serves 2-3 individuals, or one if you are particularly thirsty or in need to fight off scurvy:Ice

1 Cup Blanco Rum

3 tbs. Lemon Juice (1 Lemon)

1 tsp. Sugar

1/3 Cup Water

Mix all materials together in a shaker and serve in a frosted martini glass or on ice.

The Taste Test

The original recipe is not as sweet and forgiving on the palette as the frozen versions I am used to drinking poolside in the summer. Upon first taste, I was struck by how sour the mixture was. The lemon juice cuts through the mix. Jennings Cox was right. Despite how sour it was, the lemon juice cut the harshness of the rum. The small portion of sugar hits the back of your tongue as a sweet note at the very end. Although the sheer amount of rum makes the drink still strong, it is a perfectly fine example of what a little bit of naval history can do to cool you down in the arid heat of the summer.

Try it yourself with a few of your friends and let us know what you think of it in the comment section below.

Primary Sources:

“Amid Many Daiquiris, A Club Closes,” The New York Times, January 2, 1984.

“Early Days of a Cocktail: The Daiquiri In Cuba and Baltimore,” The Evening Sun, August 22, 1952.

“Origin is Disclosed of Daiquiri Cocktail,” Miami Herald, March 14, 1937.

Secondary Sources:

“Daiquiri Room,” ArmyNavyClub.org.

“Original Daiquiri recipe by Mr. Cox,” University of Miami Libraries Special Collections. (online)

Brian Petro, “Classic Cocktails in History: The History,” The Alcohol Professor. (Blog)

“The Daiquiri,” The Rum Nerd. (Blog)

Mark Jones, “The District’s Claim to the Daiquiri,” Boundary Stones (WETA). (blog)

“The Hemingway Daiquiri(s),” To Have and Have Another. (Blog)

“The Navy Doctor & the Daiquiri,” The Grog: A Journal of Navy Medical History and Culture, Spring 2011: 23.

John Paulson

Philip Greene

Admin

Pingback: The Navy's Daiquiri Heritage Honored at Portrait Dedication | Naval Historical Foundation

Brian L. Frye