Reviewed by David F. Winkler, Ph.D.

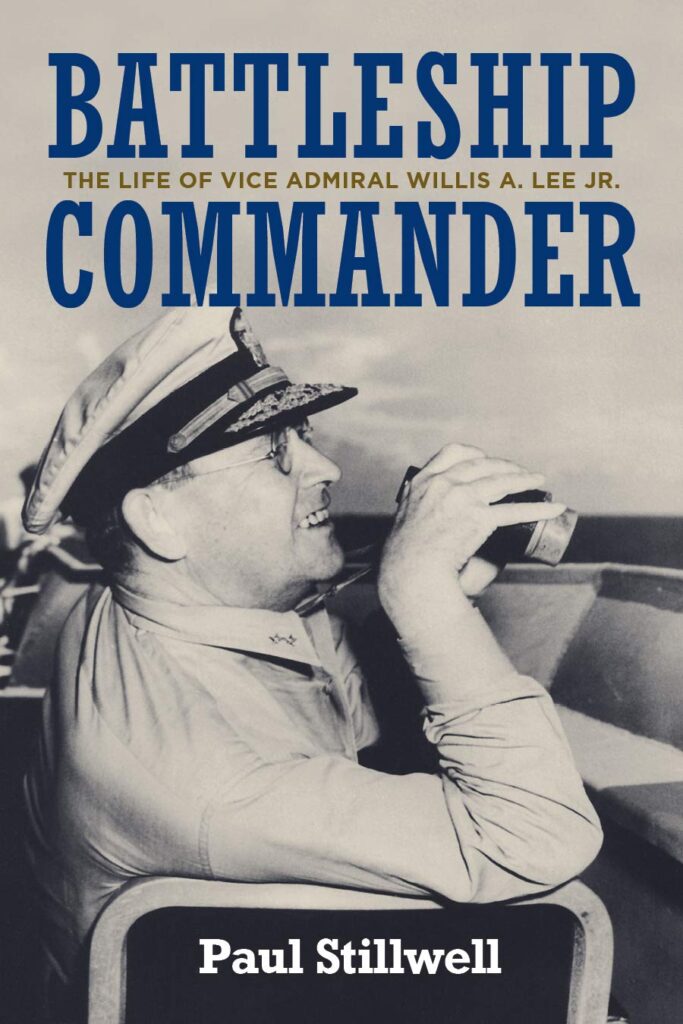

Paul Stillwell has filled one of the remaining voids in the bibliographic study of America’s World War II naval leadership with his well-written narrative of Vice Adm. Willis A. “Ching” Lee who was entrusted with command of the American battleline during the Pacific war against Japan. Such a position, merely a decade earlier, would have placed him at the pantheon of American naval leadership during the war. Yet with aircraft carriers supplanting battleships as the primary capital ship in the wake of Pearl Harbor, the big-gun combatants would be relegated to shore bombardment and fleet air defense duties.

There were some notable exceptions and thanks to the late James Hornfischer’s Neptune’s Infernal and Trent Hone’s Learning War, we have a greater appreciation of the contributions that gunships of various tonnages made during the war. Stillwell’s work broadens our understanding that the American naval narrative extends beyond Coral Sea, Midway, and the Marianas Turkey Shoot. That it took eight decades after the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, to publish this book about such a significant naval leader is a story in itself.

Stillwell began working on this biography over four decades ago which was inspired by his assignment during the Vietnam War to the battleship New Jersey – one of Lee’s former flagships. Fortunately for Stillwell, he was not the first to recognize the significance of Lee’s career. Evan Smith, a journalist from Lee’s home county in Kentucky, followed the exploits of the young lad once known as “Mose” and compiled quite the collection of newspaper clippings, correspondence, and other biographical materials. Yet despite Stillwell’s access to this trove of material left by a deceased reporter, a thorough study of Lee presented an uphill challenge. Lee distained publicity and rarely allowed himself to be interviewed. He kept no diary. Furthermore, he died before V-J Day so there were no opportunities for oral histories or memoir writing.

For Stillwell, his duties with the U.S. Naval Institute to conduct oral histories, editing the journal Naval History, and taking on other book projects to include studies on the battleships Arizona and New Jersey as well as the award-winning Golden Thirteen overview of the Navy’s first African-American officers kept this project on the back burner. However, it is evident that this published 2021 edition benefitted from Stillwell’s biographic oral history work with numerous officers who had served under Lee. Stillwell’s work also drew from some of the more recent scholarship on the Pacific War to include the aforementioned Hornfischer and Hone, but others such as Richard Frank and Evan Thomas. It’s lauded that he is not timid about giving such authors a shout out in his narrative and quote some of the finer prose from these authors of previous work to enhance the narrative.

Stillwell employs two writing styles in covering Lee’s life. One reason Stillwell is a repeated guest on the Naval Historical Foundation’s monthly Second Saturday webinar is that he is a master teller of short vignettes. Such is the case in the chapters leading up to World War II where Stillwell tells the Lee tale through a continuous chronological string of short stories about Lee’s upbringing in rural Kentucky, his time at the Naval Academy where he got tagged with the “Ching” nickname that he fully embraced, his success as a marksman with both rifle and pistol, his courtship and marriage to Mabelle Allen who he affectionately called “Chubby,” and his various duties following his graduation for the Naval Academy in 1908 through World War I and into the interwar period. Of note, the U.S. Navy’s top battleship commander during World War II never had a battleship command before the war.

A chain smoker, Lee was not a spit and polish type of guy. In discussing his duties with the Fleet Training Division at Main Navy prior to World War II, Stillwell writes: “He was far less interested in which ships won Es for excellence than determining the maximum capabilities of men, ships, and weapons, then finding the best way to employ those capabilities.” (p. 88)

Stillwell’s style changes from vignettes to synthesis as Lee, ordered to the South Pacific to command the Navy’s new fast battleships, finds himself engaged on the night of 14-15 November 1942 in part II of what became known as the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Here Stillwell builds on the narratives of Morison, Frank, Hornfischer, Hone and others to incorporate materials from oral histories, interviews, and action reports to write a climatic chapter where Lee’s task force of two battleships and four destroyers confront a Japanese surface action group of cruisers and destroyers centered on the battleship Kirishima. The Americans suffer the loss of three destroyers and heavy damage inflicted on the fourth destroyer and battleship South Dakota but Washington’s broadsides succeed in adding Kirishima to the floor of Iron Bottom Sound and force the Japanese to abandon their campaign to wrest control of Guadalcanal from the Americans.

Stillwell addresses Lee’s decision not to venture forth from Saipan for a surface engagement in the Battle for the Philippine Sea that became noted for a defensive air engagement dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. He then delves into the lost opportunity during the Battle of Leyte Gulf where miscommunications between the Third and Seventh Fleets left San Bernardino Strait open for Vice Adm. Takao Kurita’s Center Force to threaten the American invasion force off Samar. Had Lee been detached by Adm. William F. Halsey to guard San Bernardino Strait, a repeat of the Surigao Strait engagement would have added considerable luster to what today is regarded as a somewhat controversial victory.

With the arrival of Kamikazes as an unanticipated threat to the fleet, Lee is ordered home in command of Task Force 69, an experimental unit based at Casco Bay, Maine to develop AA tactics and evaluate weapons systems to counter the suicide aircraft. With the detonations of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki causing the Japanese to sue for peace, Lee’s mission became superfluous and as Stillwell points out, his reason for existence. On August 25, 1945 he died of a heart attack.

As a retired Surface Warfare Officer, I highly commend this study in leadership to all SWOs. As unbelievable as it may seem, Vice Adm. Willis A. Lee is NOT in the Surface Navy Association Hall of Fame. This oversight needs to be corrected.

Dr. Winkler is the staff historian with the Naval Historical Foundation.

Battleship Commander: The Life of Willis A. Lee Jr. (Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2021).

Barrett Tillman