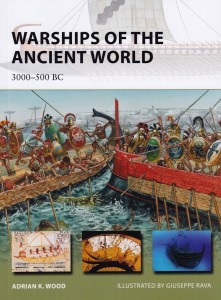

Written by Adrian K. Wood and Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava. Osprey Publishing, Ltd., Long Island City, NY. (2012)

Written by Adrian K. Wood and Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava. Osprey Publishing, Ltd., Long Island City, NY. (2012)

Reviewed by John R. Satterfield, DBA.

Writing about human activities in the Bronze and early Iron Ages is a daunting task. Evidence from these eras is fragmentary at best, like a jigsaw puzzle with far more pieces missing than available. Focused examinations on specific topics must rely on even sketchier resources. Earliest examples of writing or illustrations that survive are typically clay tablets or inscriptions on monuments or buildings, and nearly all of these artifacts are remnants.

From this standpoint, Adrian Wood’s little book on ancient warships in the Mediterranean and Middle East, really a bound essay, is a serviceable primer to an obscure topic, made even better by photos and line drawings from original relics and color illustrations by Giuseppe Rava showing various ship profiles and depictions of vessels in action.

Wood covers the period between 3000 and 500 BCE, roughly contiguous with the dawn of writing and recorded history, in the Mediterranean, and the Bronze Age. By this time, ship construction, a natural outgrowth of the region’s dependence on the Mediterranean for commerce and trade as well as exploration and conquest, was well developed, probably originating on the Nile in Egypt and rivers in the Fertile Crescent. Boats using rudimentary sails and paddles or oars traveled between villages by hugging the Mediterranean coastline. These tiny craft evolved gradually into larger vessels capable of carrying significant cargoes or numerous passengers on longer voyages in open water. Sea voyages also facilitated warfare, as tribes with access to the coast launched expeditions to loot adjacent areas and enslave potential rivals.

Early on, however, vessels used for conquest were not purpose built and handled a variety of commercial and military missions. As societies grew larger and more sophisticated, rivalries intensified, and regional kingdoms developed ships capable of defending their coasts from all too frequent raids. Not all such societies, of course, had comparable maritime capabilities. Ship building required timber, a scarce commodity in Egypt and North Africa, and early civilizations focused much of their wealth and power, if they enjoyed these advantages, on acquiring construction materials. Those who could build fleets quickly achieved dominance, sometimes extending through centuries, over less fortunate kingdoms.

Wood begins his review of ancient warships in Egypt, exploring the types of ships they used based on illustrations and other documentary evidence, probable construction techniques and maritime tactics. He follows this approach with other civilizations, arranged in loosely chronological order, covering on the societies that relied on the sea for their perpetuation. After touching on the Sea Peoples, a nomadic group of indefinite origin who are known almost entirely from the derivative descriptions by the kingdoms they attacked, the author turns to the Minoan Crete, Bronze Age Syria, Phoenicia and the city states in the Levant, and finally pre-classical Greece.

The extent of Wood’s evaluation of each of these societies is based on the availability of illustrative and documentary materials from each period and the relative importance of maritime activity in the cultures reviewed. For example, at least a third of the narrative focuses on Greece, and I’m sure this emphasis derives from the relatively large cache of information already presented in numerous scholarly works, not cited in the text but several of which the author thoughtfully includes in a brief bibliography that also relies on primary sources ranging from the Old Testament to Greek histories and commentaries.

Many readers with interest in ancient warships are familiar with the trireme and its extensive role in Greek maritime war-fighting during the classical period, but this book is useful because it clearly describes the developmental thread from much earlier designs that originated millennia before the trireme appeared. Design elements in early vessels cross cultural lines and provide a consistent foundation for subsequent improvements. Ancient galleys, used for war and commerce, contained a single row of as many as 25 oars port and starboard, a single mast with a simply rigged square sail, usually furled during combat, large steering oars for directional control and often a ram on the prow. Dedicated warships utilized a narrow deck between the oarsmen for archers or other troops and platforms or castles at bow and stern for boarders. Greek pentekonters , narrow-beamed vessels with single rows of 25 oars, and later hekatonters with double rows of up to 120 oars in similar-sized hulls, were streamlined versions of earlier multi-role ships and used almost always for warfare, leading directly to the trireme.

Wood’s essay is a nice introduction to a little-studied subject and is worth the time to read if only to show the long, steady advance in maritime technology in the Mediterranean that made naval vessels and subsequent developments such a critical part of global military and naval history.

Dr. Satterfield writes on military topics and teaches history and business at Wilmington University in New Castle, Delaware.