By Captain George Stewart, USN (RET)

This is the fifth in a series of articles by Captain Stewart detailing the technical specifications, manning, and operations of the U.S. Navy’s Fletcher class destroyers.

This is the fifth and last article in a series describing life aboard a World War II built Fletcher Class destroyer during the post World War II era (For links to my previous articles click here). This article describes my personal experiences during my assignment to the USS Halsey Powell (DD 686) during the period 1956 to 1959.

My experiences began in August 1956 when I was about to graduate from the Massachusetts Maritime Academy (MMA). As graduation approached, we had a disquieting piece of news concerning the status of our naval reserve (USNR) commissions. The legislation that covered our program had expired after our first year and it had become necessary to find us another program. The solution was to enlist us as Officer Candidate, Seaman Apprentice (OCSA) USNR. Shortly before graduation it was announced that we would all be required to serve three years on active duty.

The next thing we knew, it was time for graduation. The week following graduation was spent in limbo. We were waiting to see what the navy intended for us. After a few days wait, I received a phone call from a secretary at the Boston Office of Naval Officer Procurement (ONOP). She informed me that I would be going to San Francisco for further transportation to a destroyer based in San Diego, California. I was directed to come in to be sworn into the Navy and pick up my orders.

The next day, I reported to the Boston ONOP. A grizzled Chief Petty Officer told me to get into line for processing. I quickly discovered that the line was for people who were applying to enter MMA. I went back over to the Chief and explained that that was not what I was there for. He looked at me rather puzzled and said “You are too young to have a commission”. I can’t blame him for this impression. I was still a few weeks short of my 21st birthday and I looked very young. Finally, I was taken in to see the Officer in Charge, who swore me in as an Ensign, USNR, and issued me my orders.

The next step was to figure out how to get to San Francisco. This was not so easy in 1956. The trip would require about 12 hours on three different airplanes with intermediate stops in Providence, New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. All planes were propeller driven. Jets would not come until a few years later. I had never been on an airplane before.

It finally came time for departure. I put on my uniform and packed my bags. My parents took me to Logan Airport. I said good-bye to my parents and very nervously boarded the DC3 that was waiting at the ramp. After what seemed like an interminable wait, the engines came to life, and we taxied out to the end of the runway. I had no idea what the future held and I was too nervous about the takeoff to give it much thought. Finally we roared down the runway and lifted into the evening sky.

We finally arrived in San Francisco about 10 AM and I took a limousine to the Federal Building downtown. I had not slept and I felt very dirty. In theory, I was reporting in for further transportation to my new ship, the USS Halsey Powell (DD 686). I had no idea of its location, but it turned out that it was still deployed to the Far East. At the Federal building, I was told to proceed to the Receiving Station at Treasure Island. I took a taxi out over the Bay Bridge. At Treasure Island, I was informed that my orders had been modified and that I was to proceed to San Diego for a four week CIC (Combat Information Center) Watch Officer Course. The school was located on Point Loma. I caught a flight to San Diego. We landed at Lindbergh Field in San Diego about 6 PM. I proceeded to check in at the Naval Station gate on 32nd Street. I was directed to report in to Commander Cruiser Destroyer Force, Pacific (COMCRUDESPAC) who turned out to be aboard the USS Dixie, a destroyer tender which was moored out at a buoy in the harbor.

San Diego had not really blossomed into the metropolis that it is today. There were no freeways. The land around it all appeared to be very parched and dry. It looks much greener today, because of irrigation. To go to Coronado, you had to take a ferry. There were constant airplane noises at night, from jet engines being tuned up over at the North Island Naval Air Station. Almost all meaningful activity seemed to center around the various naval activities around the bay. The main commercial airport, Lindbergh Field was (and still is) located in the heart of downtown San Diego.

The main street of San Diego, Broadway, was lined with locker clubs and tattoo parlors. In those days enlisted sailors were not allowed to have civilian clothes aboard ship and it was necessary for single men to leave them ashore in a locker club. These institutions have since disappeared. As discussed in my previous article, sailors were provided with passes called “liberty cards” which had to be shown to the Officer of the Deck on the quarterdeck when departing from or arriving aboard ship. A favorite place for sailors and junior officers to go on liberty was Tijuana, Mexico which is only a few miles to the south.

After completion of CIC School I heard that the Halsey Powell had returned to San Diego and could be found at a pier at the 32nd Street Naval Station. At that time, most of the ships moored at buoys in San Diego Harbor and could only be reached by ship’s boat or water taxi. The only time most ships got to a pier was immediately after returning from a deployment.

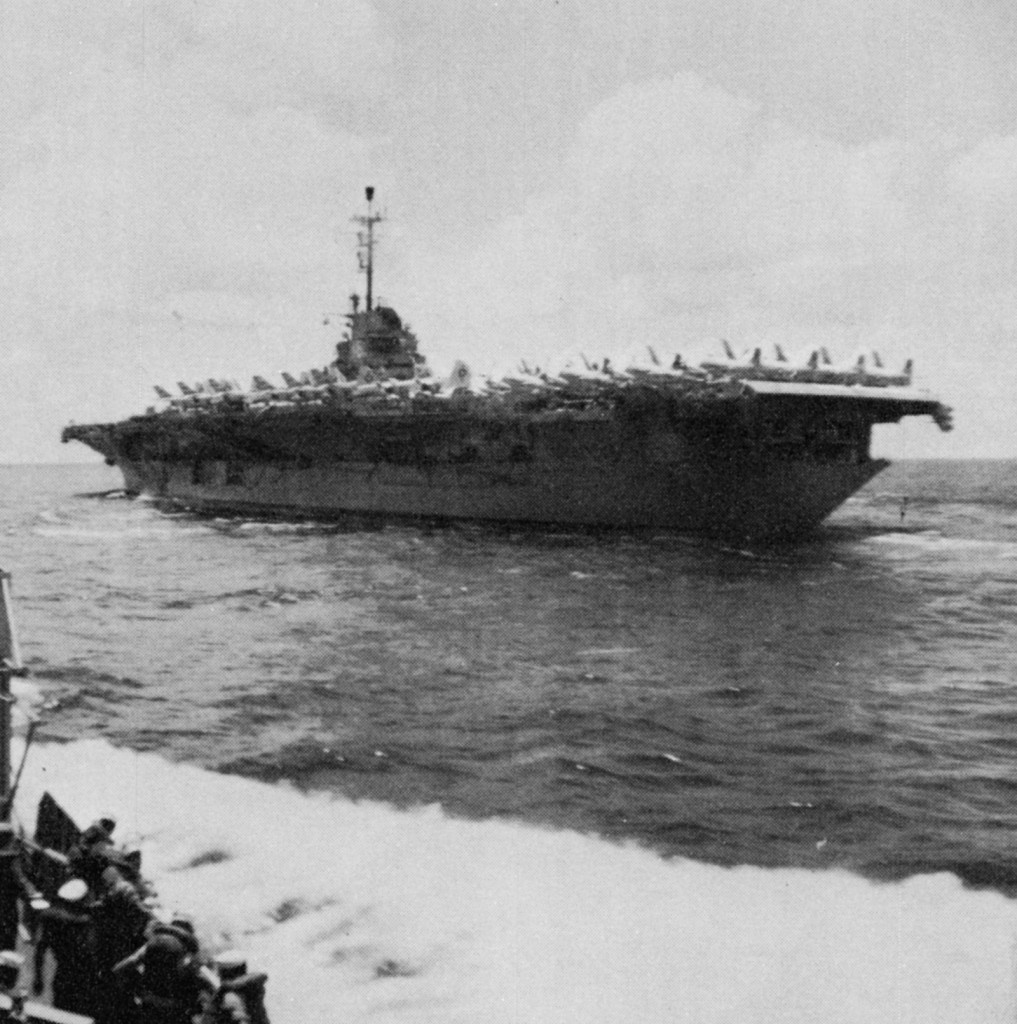

First, a bit about the Halsey Powell itself. The ship was built at Bethlehem Steel Co., Staten Island, New York. It was launched on 30 June 1943 and commissioned on 25 October 1943. Its initial shakedown was conducted in the Bermuda area and in January, 1944 it set sail for duty in the Pacific Fleet. Its entire service life would be spent in the Pacific. The ship participated in most of the major operations in the Pacific during 1944 and 1945. Specific campaigns that the ship was involved in were the invasions of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, the Marianas Campaign, strikes against Okinawa, Taiwan, Philippines, and Japan. The most dramatic moment occurred on 14 March 1945 when, in the process of fueling alongside the carrier USS Hancock, the ship was struck on the fantail by a kamikaze. Although the rudder was jammed hard left, a collision was narrowly averted. However the ship was required to return to the states for battle damage repair. It sailed for the Far East in July 1945 and shortly thereafter, wound up in Tokyo Bay where it anchored for the surrender ceremonies on August 27, 1945. In October, 1946, the ship returned to the West Coast and on 10 December 1946 it was decommissioned and placed in the reserve fleet in San Diego.

The outbreak of the Korean War caused a requirement for more destroyers and Halsey Powell was placed back in commission on 21 April, 1951 as part of Destroyer Division (DESDIV) 171. The division consisted of four Fletcher Class destroyers. The other three ships in the division were the USS Gregory (DD 802) (flagship), USS Porterfield (DD 682), and USS Marshall (DD 676). Between April 1951 and May 1953, the division made two seven month deployments to the Far East where it operated as part of Task Force 77 in support of operations in Korea. During this period the ship operated in support of carrier task group operations and participated in shore bombardment.

During the subsequent years the ship continued to make annual six month deployments to the Far East (we called it “WESTPAC”) where it participated in a variety of operations of the type that I described in previous articles. When I made my first visit to the ship it had just returned from its’ sixth deployment since re-commissioning in 1951. This cycle was to continue throughout my time aboard the ship. It resulted in a lot of time away from our home port.

Finally, I finished all of my schools and I packed my bags and checked out of the Bachelor Officers Quarters (BOQ). By now, the ship was out at a buoy in San Diego Harbor. I left my car in the BOQ parking lot and took a taxi to Fleet Landing which at the time was located approximately where the USS Midway Museum is now. It was late in the evening and there were many sailors returning from liberty. This was a very active place in those days, with ships boats and water taxis continually coming and going. The scene was controlled by the Shore Patrol, who were continuously announcing arrivals and departures over the public address system. I finally arrived on board in November, 1956. I soon met the rest of my new shipmates. The atmosphere in the wardroom appeared to be quite friendly and relaxed.

Destroyer Squadron 17, San Diego, California, March 1955. USS Halsey Powell is in front, second from right. NHHC image NH 91826.

The next morning, I got up bright and early and went down to see the Executive Officer (XO). I had previously written him a letter asking for assignment to engineering because this was what I had been trained for but he told me that I was to be the new First Lieutenant. I was somewhat dismayed, as this was not in line with my MMA training, however I decided to make the best of it. I went back up to the wardroom and asked about the ship’s schedule. I was also told that the ship would be going in for a 3 month overhaul at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard in mid December and that it was scheduled to go on a six month deployment to WESTPAC the next May. About that time, the Chief Engineer came into the wardroom. We struck up a brief conversation and he asked where I had gone to school. When I told him MMA he asked me what the XO told me my assignment would be. When I told him “First Lieutenant” he said “WHAAT ” and jumped up and headed below to see the XO. A few minutes later, I was called back down to see him. He told me that they had changed my assignment and that I was to be the Main Propulsion Assistant (MPA). This seemed to make sense to me.

The Navy which I entered was essentially that of World War II. It was only 11 years since V-J Day. At least 90% of the ships had been built during, and in some cases prior to the war. The bulk of the Pacific Fleet Cruiser-Destroyer Force (CRUDESPAC) consisted of Fletcher and Gearing class destroyers. There were Seaplanes regularly taking off and landing in San Diego Harbor. COMCRUDESPAC himself resided on a Destroyer Tender, which habitually moored to a buoy in the harbor. Virtually every officer of the rank of LCDR or greater had served during the war, as had most of the senior enlisted personnel.

I was now the Main Propulsion Assistant (MPA). This made me the division officer for about 55 men, all of whom either belonged to the Boiler tender (BT) or Machinist’s Mate (MM) ratings. I would have liked to provide more leadership for the division, but there were several problems. For one, I was only a barely 21 year old Ensign with no naval experience. Engineering did not appear to be very important on the ship and it showed it. We had a material inspection by the Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV) (in which I was to play an important role 25 years later) and we did very poorly with many gross safety violations. Compounding the problem was the fact that we were operating without our proper complement of CPO’s. Technically, I was fairly capable because of my MMA training, but with all of the additional duties I was given, it was an impossible burden for a 21 year old. The Commanding Officers of that generation had primarily been raised with a single objective in mind (beating the Japanese) and engineering had generally been left up to reservists and enlisted men.

I had only been on the ship for about 6 weeks when we steamed up to Long Beach for regular overhaul. The overhaul was to last about 3 or 4 months. We anchored on a foggy day off Seal Beach to offload ammunition prior to entering the shipyard. The next day, bright and early we pulled in to a pier in the Long Beach Naval Shipyard and shut down the machinery. After about 3 or 4 weeks, the Captain had announced that, since the ship was to be torn up, we could all draw an additional allowance of $97 and move ashore. Three of us decided to take him up on this and we agreed to go look for an apartment.

First, a little bit about Long Beach. At the time, there were numerous active oil wells in the surrounding area. The shipyard was located on Terminal Island, which sat right between Long Beach and San Pedro. Because of constant oil pumping, the island was actually sinking bit by bit and it had been surrounded by dikes. Later, the island was saved by pumping water under it. The island contained the naval shipyard, two private shipyards, and a few other industrial activities. There were still a few houses remaining. Access to the island was by a pair of bridges and a ferry to San Pedro. The island was connected to downtown Long Beach by a floating pontoon drawbridge which had been built during World War II. Just south of the city was a residential section called Belmont Shore. It fronted on a large, sandy beach. The place was loaded with people in their 20’s or early 30’s. There were lots of girls. Many of the men were junior engineer’s working in the aircraft industry for Douglas or North American.

After some looking, we moved in to a suitable apartment only one block off the beach. While we were there, I met my future wife on a double date. Unfortunately, the overhaul was soon coming to a close and the ship would soon be returning to San Diego.

Aboard ship, we were preparing to leave the yard and return to San Diego for Refresher Training. We were scheduled to leave on a 6 month deployment to the Far East in May 1957. We were paid a brief visit by our placement officer from the Bureau of Personnel in Washington. At that time, the captain pointed out that both the Chief Engineer and Damage Control Assistant (DCA) were due to leave the ship within the next few months and that no relief for the Chief Engineer had been named. The placement officer pointed to me and said “How about him?” Both the captain and executive officer strongly protested that this was a Lieutenant’s billet and that they could not assign it to a 21 year old Ensign with only 8 months in the Navy. Apparently their protests fell on deaf ears because about one week later the Chief Engineer informed me that I was to be his relief. We completed sea trials and returned to San Diego.

By this time, I had things to occupy myself. The ship was due to deploy in about 2 weeks. I had just enough time to sign for the Engineering Department equipage, salute my predecessor, and say “I relieve you sir.” To put the whole thing in perspective:

- I was 21 years old.

- I had 8 months in the navy.

- I was an Ensign filling a senior Lieutenant’s billet.

- I was now a department head.

- I was filling one of the most important jobs on the ship.

- I was expected to stand 8 hours per day of underway watch in CIC.

- I only had been underway on the ship for about 4 weeks.

- I was the only officer on the ship with any significant understanding of marine engineering.

On the positive side, I did understand shipboard engineering fairly well and I really wanted to do a good job. But I had an impossible task for a 21 year old.

After leaving San Diego, our first port of call was Pearl Harbor. It was very pleasant, but we only stayed for about 2 days, prior to proceeding onward. The next stop was in Midway, only long enough to take on fuel. The next stop was in Yokosuka Japan, for an upkeep period. It was only five years after the end of the U.S. occupation and the country had not really had a chance to rebuild. Nevertheless we found the Japanese to be quite friendly. Yokosuka was definitely a sailor town at the time with many bars and Geisha houses. Our favorite dish was sukiyaki and I learned to eat with chopsticks.

From Yokosuka, we proceeded out to join the Seventh Fleet. Our job was to act as an escort for the USS Lexington Carrier Battle Group. Most of the time was spent in a bent line screen station, with occasional assignment to plane guard duties behind the carrier. About 8 destroyers were assigned to the group. The carrier had to periodically turn into the wind while launching and recovering aircraft and then turn back out of the wind until the next operation. Every time the carrier changed course, the screen had to be re-oriented and it seemed like there were destroyers flying all over the place. Our job in CIC was to track the other ships and provide the OOD with recommendations on how to get to our new station. Plane guard consisted of following closely behind the carrier in a state of readiness to recover a downed pilot. About every three or four days we would conduct an underway refueling operation alongside a carrier or an oiler. We spent most of our time at sea. At one stint, we were away from land for 35 days. The food was bad. We only had powdered milk and ice cream available and both were awful.

Our next port call was in Kaoshiung, Taiwan. The harbor was entered through a very narrow entrance between two cliffs. Inside, it was very hot and the stench from the open sewers was unbelievable. One of my most vivid memories is drawing shore patrol duty in Kaoshiung on 4 July, 1957. It was hotter than hell.

Another port we made was Sasebo, in Southern Japan. It was not too far from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but, I never got a chance to go over there because, being the Chief Engineer, I was always too busy in port.

About halfway through the cruise, I was mercifully taken out of CIC and assigned duties as Junior Officer of the Deck (JOOD). I had actually been a dreadful CIC Watch Officer, but now I began to get some idea what was actually going on topside. I actually enjoyed the JOOD watches.

During the later stages of the cruise, we stopped in Hong Kong. It was a very prosperous and bustling city even then, although it was not really to take off until after the establishment of jet travel a few years in the future. There was a great sense of adventure because of our proximity to Communist China. The Chinese takeover of Hong Kong was many years in the future.

Our last port of call was Yokosuka again. A shipmate and I took a train up to Tokyo. It was well worth it. It is necessary to see a major Asian city at night in order to appreciate it. There were many colorful neon lights and lighted balloons floating over the city. We walked around the royal palace and down the Ginza. Prince Akhito was just about to be married and there were pictures of him and his new wife all around the city.

From Yokosuka we headed home. Again, we had a brief fueling stop in Midway. Between Midway and Pearl Harbor, the commodore put us in a line abreast and we did our annual full power runs. Although he had put out a message telling us that this was not a race, none of us believed him. Halsey Powell could still get up and run at about 35 knots with the forced draft blowers wailing, the ship vibrating, and a great towering wave following the ship.

By this time, I had been qualified as an Officer of the Deck (OOD) underway. Unfortunately, I was not really ready for this assignment, having not really had enough time as a JOOD. This was to come back to bite me later on.

A Fletcher class destroyer could carry barely enough fuel to get back to San Diego without refueling. We would arrive with about 17-20% in our tanks and we had to take on sea water ballast in order to remain stable. This was a very messy operation which would not pass muster today, as we discharged all of this ballast as oily residue at sea.

Finally we got back to San Diego in November 1957. With some direction, I was allowed to make the landing at the San Diego Naval Station, whereupon I was told that I was now qualified as a Command Duty Officer (CDO) in port. The CDO is the officer in charge of the ship when the CO and XO are ashore. This was very premature.

Of course, I assumed that my girl friend would be back in Long Beach on my arrival. Actually, it turned out that she was. As soon as I could escape from the ship, I headed for Long Beach. In those days my transportation was by Greyhound Bus from San Diego up Highway 101.

It just seemed that the natural thing to do was to get married. I had some definite reservations. I was only 22 years old and not very world wise, but I was not sure that this opportunity would come around again and it definitely seemed like the correct thing to do. We set a date of 22 March, 1958.

Some major changes were taking place aboard the Halsey Powell. In late January 1958, we had a new commanding officer. This was to be his fourth ship command. A problem which was common to many of the Commanding Officers of that era was the fact that they had been advanced very rapidly into XO and, in some cases command billets due to wartime pressures. As a result, they had not really served apprenticeships in the various departments aboard ship. Engineering had always been considered as non-career enhancing. This meant that, effectively, I remained my own boss.

The biggest problem that I had with the new Captain was that I had been advanced into the OOD and CDO positions far too rapidly and I could not meet his demanding standards in these areas. I developed a phobia toward watches on the bridge. Looking back, this was very unfortunate, as later on, this actually became one of my strongest areas, once my attitude had been turned around.

About this time, having completed the requisite 18 months of commissioned service, I was promoted to the exalted rank of Ltjg. This gave me a little more status and my base pay was increased from $222 to $259 per month.

My wedding date was coming up very rapidly. I was supposed to go to Long Beach on 15 March to obtain a license. A big reception had been set up for that weekend with the entire Belmont Shore crowd invited. We had been out for a week’s operations and I remember being up on deck on Friday evening watching Point Loma come up as we began our entry into San Diego Harbor. Suddenly, the ship made a sharp turn to the left, increased speed to 25 knots, and proceeded northwards. Rather dismayed, I went up to the bridge and discovered that we were proceeding up to the area off the Golden Gate to investigate an unidentified submarine contact. By now, I was a bit frantic, but there was not very much that I could do about it. There were no cell phones in those days. When I did not show up, my prospective bride became convinced that I had absconded and that I had left instructions with Ship’s Information in San Diego not to tell her anything. Naturally, the reception and wedding were canceled.

We never did find any submarines, but after about 3 or 4 days, I finally got ashore in San Francisco. I thought of flying back, but, the captain was reluctant to go to sea without me. I called her, explained the situation, and said that I would see her in Long Beach on the next weekend. The wedding would end up on schedule. We promptly set out for our new home in San Diego. We had rented a small apartment in Pacific Beach.

I received orders to inactive duty in August of 1958. This came as a total surprise. We had been originally commissioned as Ensigns in the Naval Reserve and told that we had three years to serve on active duty. The ship was placed into a quandary as there was no qualified relief for me on board and the ship was scheduled to deploy shortly thereafter. A quota was promptly obtained for an ensign in the gunnery department to attend 12 week engineering school. Meanwhile the XO managed to sell me on the virtues of a Navy career and convinced me to apply for augmentation into the regular Navy. I was promptly accepted as a Ltjg USN. This basically bound me to the navy for life, or so I thought at the time.

The next burp was when the 1958 Lebanon Crisis occurred in July and we were told to start recalling personnel to the ship. Since all of the officers senior to me were on leave or off the ship, I was the acting XO and had to start the recall process in motion. Complicating the matter was the fact that I had a forced draft blower off the ship being overhauled and a hole had been cut in the main deck to permit its removal. Sure enough, we were told to deploy to WESTPAC immediately, about 6 weeks early. Our date of return was uncertain.

I got off the ship long enough to explain what was happening to my wife. My last night before deployment was spent at the Ship Repair Depot in San Diego seeing to my broken machinery. The yard workers were still on board welding up the hole in the deck as we proceeded out the channel. We let them off in a boat on the way out. With a sinking feeling, I saw Point Loma recede over the horizon.

Our ports of call on the way out were Midway, Guam, and Sasebo. During the course of the trip to WESTPAC, the international situation had turned into a dispute between Communist and Nationalist China over the islands of Matsu and Quemoy. From Sasebo, we proceeded to Kaoshiung. From there, we went out to patrol the Straits of Formosa as a unit of Task Force 72. In the later part of this period, we were primarily involved in escorting convoys of Nationalist Chinese ships out to the islands of Matsu and Quemoy. At night, you could see the flashes of gunfire on the horizon from the mainland to the islands.

The ship left Formosa Patrol on 28 September 1958 and proceeded to Buckner Bay, Okinawa for a brief port stay. From there we were sent to Subic Bay in the Philippines for a 9 day upkeep period. During one stint in the South China Sea, we went through the edges of a typhoon. As a junior officer, our captain had been on a destroyer which had been in Admiral Halsey’s task group when it went through a typhoon and several destroyers had capsized and sunk due to low fuel state.

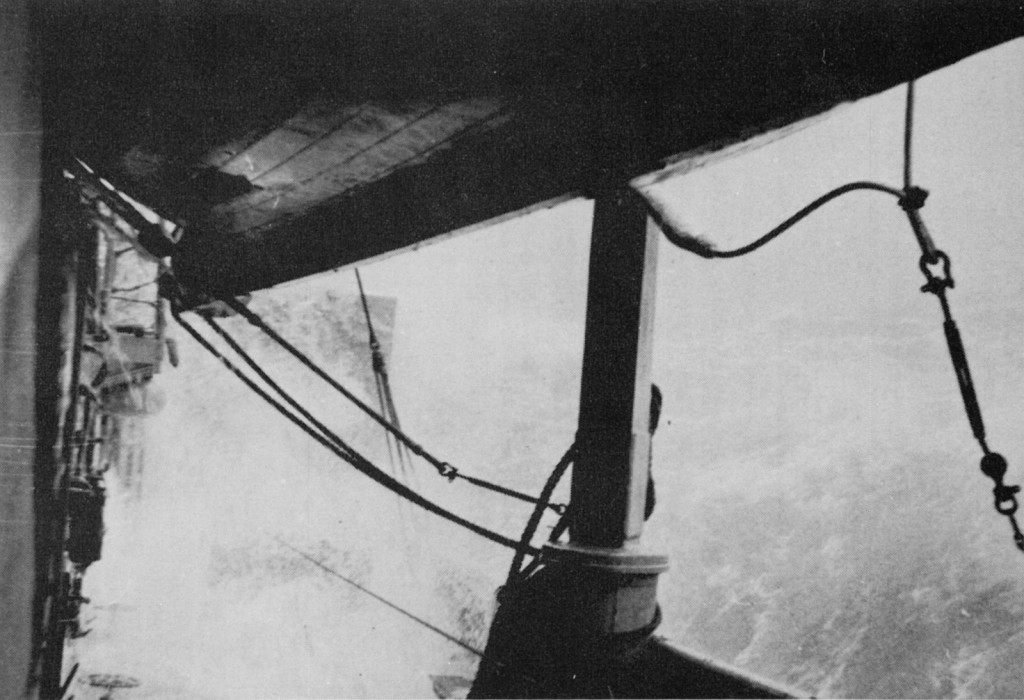

The Fletcher class destroyers had one major weakness. It was necessary to go outside on the weather deck in order to get from the forward to after parts of the ship. During heavy weather such as the typhoon, one end of the ship was effectively cut off from the other. During the typhoon, our gunnery officer was nearly washed overboard when he had to go out on deck to ensure that the ship’s depth charges were secured. He wound up hanging onto a lifeline. To get to the main engine control station, I had to go outside on the main deck and enter through a vestibule that led into the ship’s laundry. I saw a large wave breaking over the ship and I grabbed onto a valve handwheel on the superstructure and held on tightly. I was submerged from head to foot. Later destroyer designs, including the Sumner and Gearing classes incorporated an enclosed passageway inside the superstructure.

In the middle of this mayhem, a loud cracking noise was heard and the upper part of the ship’s mast began waving around precariously. A Boatswain’s Mate was sent aloft to tie it down, but his efforts were not very effective. We were told to return to the Ship Repair Facility (SRF) at Subic Bay, Philippines for repair. A mast replacement was a major operation which would take us off the line for a month. I did make one brief visit to the town of Olongapo, just outside the gate of the naval station. The main street of the town was unpaved. The principal mode of transportation appeared to be World War II Surplus Jeeps (Jeepneys), all painted in bright colors and bedecked with flags.

One duty that I always despised was breaking an encrypted message. At the time, this could only be done by a commissioned officer. It was necessary to look up the key list for the day and laboriously assemble a group of rotors into the machine in the correct sequence for that date. When the message was typed it would come out in plain language. One evening, it was my turn to perform this duty. I could not believe my eyes when the message that I was breaking said to join up with the rest of the division and proceed to Yokosuka for a brief port visit and from there to proceed home to San Diego. I ran to the Captain’s cabin to give him the good news. We were due back in mid December.

The trip back was essentially a blur. I remember a brief stop in Pearl Harbor after which the commodore put the division into a column and had us run close by Waikiki Beach at 25 knots in order to impress a woman that he had formed an association with the night before. The captain, ever mindful of the necessity to conserve precious fuel during the transit, was fit to be tied.

We arrived in San Diego, as scheduled, on 21 December 1958. My wife was waiting on the dock, along with all of the other WESTPAC Widows. She was 6 months pregnant at the time. Around the first of March, it was time to go up to the Long Beach Naval Shipyard for overhaul. Now I was commuting in the reverse direction. Then I received word that the baby was about to arrive. I got to San Diego just in time to take her to the hospital. After a long wait, the nurse called me in and held up a baby boy. It became obvious that she and the baby needed to come up to Long Beach to be with me. I found an apartment. a few blocks from our old place on St. Joseph’s.

I was due up for rotation in July. I had a long discussion with our XO on what I should do next. We decided that the best job for me would be as executive officer of a smaller ship, such as an LST (Landing Ship Tank) or MSO (Minesweeper). Shortly thereafter I received orders to report to the USS Force (MSO 445) as XO. First I would be attending 3 weeks of Minesweeping School in Charleston, South Carolina. The ship was home ported right there in Long Beach.

We completed our overhaul and I turned the Chief Engineer’s duties over to my MPA. I was confident that I was leaving things in good hands. Nevertheless, I felt a great deal of sadness at leaving. Halsey Powell had been a very important part of my life for the past 3 years and I was leaving a lot of friends behind.

As a post script, in 1965, Halsey Powell was transferred to be the Naval Reserve Training Ship in Long Beach. It was transferred to the South Korean navy in 1969 where it was renamed the R.O.K. Seoul. It was stricken from the U.S. Naval Register in 1975 and was decommissioned and scrapped in 1982.

George W. Stewart is a retired US Navy Captain. He is a 1956 graduate of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. During his 30 year naval career he held two ship commands and served a total of 8 years on naval material inspection boards, during which he conducted trials and inspections aboard over 200 naval vessels. Since his retirement from active naval service in 1986 he has been employed in the ship design industry where he has specialized in the development of concept designs of propulsion and powering systems, some of which have entered active service. He currently holds the title of Chief Marine Engineer at Marine Design Dynamics.

Pingback: Fletcher Class Destroyer Operations - Part II | Naval Historical Foundation

David R. Murphy

George W. Stewart

larry gorvin

Chuck Weston

Indy

Harry Curtis

Jim Gillum

George D. Richardson

Edward

Dick Bee

Michael Halldorson

Howard N. Freeman MMC ret

John Puff

Scott M. Kruchell

Doug Shaver

Frank Schulte

Alan T. Butler

Dick allen

George W. Stewart

Donald R. Mighell

George W. Stewart

Sandy Lung

George W. Stewart

Henry Watson

Chuck Weston

Mike Casey

Gordon Pelton

George York

al pilz

bob kittel

Jerry Palmateer

Pete Pultz SO2

JAMES LILLEY

JAMES LILLEY

JAMES LILLEY

DENNIS BARSTOW