By Norman Polmar

(Editor’s note: This is the eighteenth in a series of blogs by Norman Polmar—author, analyst, and consultant specializing in the naval, aviation, and intelligence fields. Follow the full series here.)

We often tend to use terms and words to describe people that, when we learn the true meaning of the word, often does not apply. But James (Jim) Fahey truly was a curmudgeon—defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “a person (especially an old man) who is easily annoyed or angered and who often complains.”That was Jim, precisely.

When in my early teens my father drove me to a magazine shop—there were such places—where I plunked down two dollars and purchased a copy of the sixth edition of Fahey’s The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, published in 1950 (this was a later printing).

Back at home I devoured the 48-page, 9 ½ by 6-inch paperback. There every U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ship was listed, characteristics given, and a thumb-nail photo provided. Of course, I had to break the code—AA meant Atlantic Active, *33 meant that the data was on page 33, etc.

Wait! This was the sixth edition. What of the first five editions? There was a Falls Church, Virginia, post office box address in the front of the book. A postcard inquiry brought a reply listing the previous volumes and their cost. My parents wrote a check (and dunned my meager allowance).

Thus, I learned about The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet. Later, I learned a good bit about Jim from himself, and even more from Paul Stillwell’s excellent article “Fahey’s Legacy” in Naval History magazine (August 2009). The following few paragraphs are adapted from Paul’s article:

Fahey was a New Yorker who loved the Navy, but had been turned down for military service for medical reasons. He then served in the merchant marine and worked as a taxi driver. He also wrote naval articles for various publications. But he felt stymied, his widow recalled many years later, by the “butchering” that editors did to his manuscripts. As an independent-minded perfectionist, he concluded that the best way to get his work into print was to serve as his own publisher.

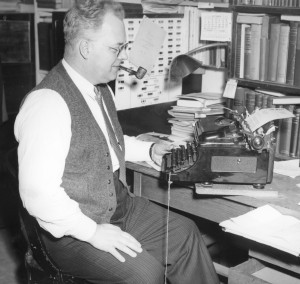

In pulling together the first edition of Ships and Aircraft in1939, Fahey was his own editor and proofreader, which was remarkable because the type was tiny and he had only one good eye. He gathered facts and figures from a variety of sources and had a fetish for accuracy. Among the features of that first edition was a three-page chart that showed the entire U.S. Fleet organization, including homeports, of the ships, including the Asiatic Fleet that operated out of China and the Philippines.

As he began selling copies of his book, Fahey commuted from his home in the Bronx to an office near Times Square in Manhattan. A youngster named Frank Uhlig, a ship lover himself, used to visit the office. Fahey told Uhlig that he left home each day with two nickels in his pocket—one for each leg of his subway trip. If the incoming mail contained money for book orders he could afford lunch that day. (Frank Uhlig, after enlisted service in the Navy, became editor of Our Navy magazine, then senior editor of the Naval Institute, and later the editor of the Naval War College Review.)

The lean times would not last long. In 1940, stimulated by the German successes in Europe, Congress passed the Two-Ocean Navy Act that opened the spigot of funding for a massive building program of ships and aircraft. Fahey responded with updated editions in 1941, 1942, 1944, and a “Victory Edition” in 1945. His work produced a bonanza of sales because of public interest in the war; a Time magazine article about him in 1942 was a major boon to his business.

And, I became one of the thousands of enthusiastic readers and fans of Ships and Aircraft. Jim produced a total of eight editions of Ships and Aircraft, with the last being actually published in 1965 by the U.S. Naval Institute. When that edition was published I called him to ask if I could purchase one directly from him. Jim invited me to come over to his home in Falls Church, Virginia.

When I introduced myself he responded, “I know who you are,” in his normal, gruff voice. (By that time I had two published books, and several articles, and was assistant editor of the Naval Institute Proceedings.) After a brief conversation he invited me to have lunch with him. His wife, Vivian, made us sandwiches—and then disappeared—and Jim and I sat in his kitchen, munching and talking for a long time. Periodically we met, usually at his home, and then ate lunch together in nearby, non-descript restaurants. These sessions usually came about because I wanted to borrow a photo from Jim. Sometimes we met at Naval Institute conferences, where his usual opening words to me were, “Still stealing my stuff, Norman?”

Jim retired with the eighth edition. John Rowe and Samuel L. Morison coauthored the ninth and tenth editions, also paperbacks.

Then, in 1977, I was asked by the Naval Institute to take over the Ships and Aircraft project. For the past decade I had been producing the several sections of the annual Jane’s Fighting Ships—the U.S., South Korean, South Vietnam, Philippine, and Taiwan navies. I also was producing the Naval Institute reference book Guide to the Soviet Navy.

I took over Ships and Aircraft with the proviso that it would be a hardback with the exact same format as Guide to the Soviet Navy. Thus, I produced the next nine editions of Ships and Aircraft through 2013, one more edition than Jim, all hardback books of several hundred pages with “big” photos. To be candid, I was not good enough to produce the small, concise, paperbacks that Jim had published!

But Jim had done me one—actually, two—better. He also produced, in his unique format, two books on aircraft: U.S. Army Aircraft 1908—1946 and USAF Aircraft 1947—1956. These listed every aircraft procured by those services, each variant, the numbers produced, and their characteristics, plus hundreds of thumb-nail photos.

I still saw Jim from time to time. He passed away in 1974. His funeral was brief and sparsely attended: His widow, his daughter from New York, a few neighbors, and two friends—Commander Don Walsh of Trieste fame and myself.

Prior to his death, Jim had sold his massive photo collection of U.S. Navy aircraft and ships to the Naval Institute. I advertised his Army-Air Force aircraft photo collection for his widow, and made a “bottom” offer in the event they did not sell. Although she received several higher offers, she insisted that I take the many boxes of photos at my lesser price. Gulp! (I was able to sell them later—at about the price I paid for them.)

Jim had handled all of the family’s finances. Thus, after his passing I helped his widow establish local credit, open a bank account, and obtain credit cards.

In my own study, above my computer, are Jim’s eight paperback editions of Ships and Aircraft, always kept within arm’s length. And, yes… I did steal from Jim, and sometimes even gave him a footnote… as well as my friendship and my admiration.

Robert Rositzke