A Four-Part Blog Series

By Matthew T. Eng

In the summer of 1943, the best baseball in the United States was played in Norfolk, VA. Unfortunately, you couldn’t just buy any ticket to see diamond stars like Fred Hutchinson, Dom DiMaggio, and Phil Rizzuto play that year – you had to enlist. This four part blog series will examine U.S. Navy baseball teams during the war and the role that the 1943 NTS Nine squad played in entertaining and transforming the culture of Hampton Roads sailors on station in Norfolk, VA.

Baseball in Norfolk radically changed the lives of the countless sailors stationed there during World War II. As a means of diversion, sailors at NTS Norfolk created their own private baseball utopia amidst the horrors of war waiting for them in the European and Pacific Theaters.

PART I: OUR WORST WAR TOWN

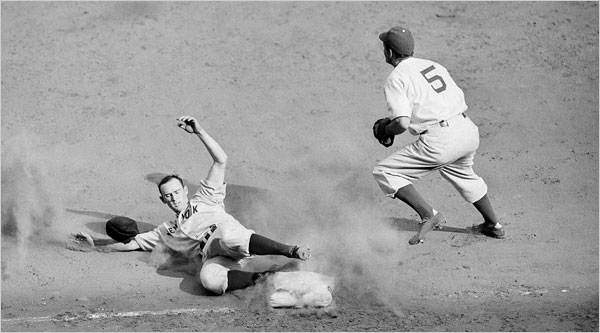

In the fall of 1941, the New York Yankees played the Brooklyn Dodgers in New York City’s first “subway series.” Fans from both boroughs huddled in seats and bleachers together to watch the country’s two best teams battle it out on the playing field. Manager Joe McCarthy’s defending champion New York Yankees defeated the Dodgers solidly in five games.

It would be the last time Americans saw a World Series in a world without war. For many others, it would be the last World Series they would ever know. The world undoubtedly changed a month and a half after the series ended, and the peaceful enjoyment of America’s pastime would be forever changed. America itself was in the batters box, waiting anxiously to step up to the plate.

To War

When the Imperial Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on the morning of December 7, 1941, Americans around the country woke up to the stark reality of a world transformed by war. Conflicts far away in Europe and Asia were now at the doorstep of Main Street. Isolationism and neutrality became impossible. It was time to fight. Norfolk, VA was not swept up in the fever of war panic that followed the attack. In direct contrast to many cities along the east coast, Norfolk was relatively prepared for the coming of war. Norfolk was on the front line of the Lend-Lease agreement between the United States and fledgling Allied powers. As historian Melvin Schlegel suggested in his masterful history of Norfolk, the town became a “conscripted city” in the early 1940s.

Thousands of men and women joined the armed forces in the wake of Pearl Harbor. Few were exempt. Famous actors, writers, politicians, musicians, and athletes also enlisted. Of this group of influential individuals, Americans looked up to those athletes who enlisted the most. Due to their mass appeal to the general public, baseball stars consistently made headlines around the country when they signed up with Uncle Sam. Their sacrifice served as a reminder that nearly anyone could fight the Axis. Many of those who signed up to serve in the United States Navy ended up at Naval Training Station Norfolk.

FROM MLB to Class I-A

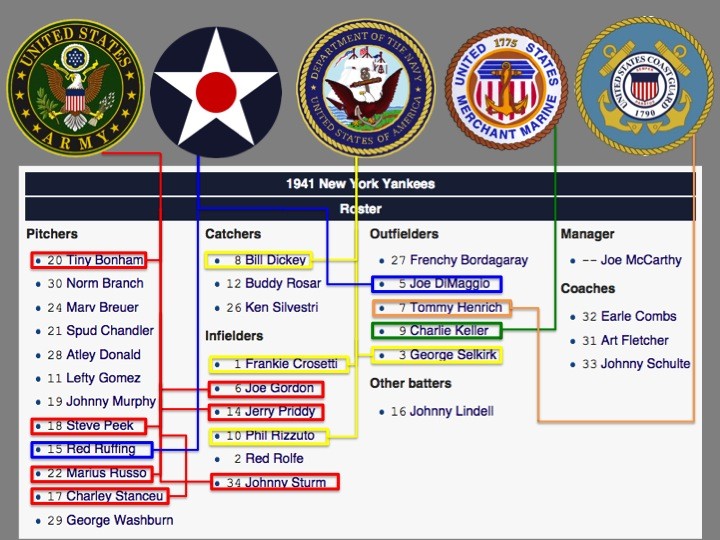

The 1942 Major League offseason was a rough one for team owners. Hundreds of baseball players, members of the country’s most popular sport, served in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine – not their old teams. The necessity for G.I.’s became evident in the early months of 1942. Rosters were depleted of top-level talent seemingly overnight.

Numerous stars of the recent World Series traded pinstripes for olive drab dungarees. The image below shows what service the 1941 World Series champions went to throughout the war:

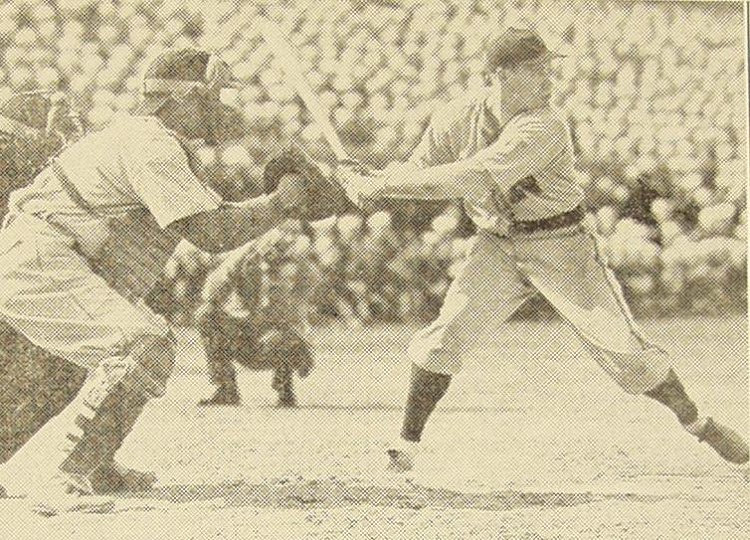

Most baseball players were relegated to the “special services” of each military branch. Their primary duty in this capacity was to boost G.I. morale by playing baseball. Joe DiMaggio, arguably the most popular sports figure in the country, went to the Army Air Corps. World Series pitcher Hugh Casey joined the United States Navy to play ball. Others like Ted Williams played a limited time on service teams before being shipped off into their respective theaters of warfare. The Triple Crown winner retired in the United States Marine Corps as a decorated Captain following the end of the Korean War.

Most baseball players were relegated to the “special services” of each military branch. Their primary duty in this capacity was to boost G.I. morale by playing baseball. Joe DiMaggio, arguably the most popular sports figure in the country, went to the Army Air Corps. World Series pitcher Hugh Casey joined the United States Navy to play ball. Others like Ted Williams played a limited time on service teams before being shipped off into their respective theaters of warfare. The Triple Crown winner retired in the United States Marine Corps as a decorated Captain following the end of the Korean War.

According to Baseball in Norfolk, Virginia authors Clay Shampoe and Thomas Garrett, one of the first ballplayers to enlist in the Navy was Cleveland Indian pitcher Bob Feller. “Rapid Robert” joined up only days after Pearl Harbor. After spending a brief time at Norfolk Naval Training Station as a fitness instructor and player for the 1942 squad, Feller transferred as a Gun Captain aboard Battleship Alabama, where he saw action extensively in the Pacific Theater. Feller remained active in his ship’s reunions until his death in 2010.

The majority of new sailors during the war were sent to either Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago or the Naval Training Station in Norfolk. Of the two locations, most sailors would rather choose the Great Lakes cold weather over the doldrums of Hampton Roads. It would only take an influx of some of the nation’s most talented athletes to Norfolk to turn its perception around seemingly overnight.

Our Worst War Town Most prewar sailors considered Norfolk as “bad duty.” A scathing report written in the February 1943 edition of H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury hailed Norfolk as “Our Worst War Town.” The article’s author spent time examining real life conditions of several congested defense towns along the East Coast. Although the author identified Norfolk as the East Coast’s “number one war zone,” Norfolk was still regarded to have the worst conditions and quality of life of any town along the Atlantic.

Most prewar sailors considered Norfolk as “bad duty.” A scathing report written in the February 1943 edition of H.L. Mencken’s American Mercury hailed Norfolk as “Our Worst War Town.” The article’s author spent time examining real life conditions of several congested defense towns along the East Coast. Although the author identified Norfolk as the East Coast’s “number one war zone,” Norfolk was still regarded to have the worst conditions and quality of life of any town along the Atlantic.

As a major terminus for war, Norfolk looked bad. Locals were concerned by their long-held reputation. With over thirty families arriving each day by 1943, it became necessary to make some changes. The July 1943 edition of Our Navy magazine published an article to rectify Norfolk’s tarnished perception often heard around town:

“Several years ago if you were transferred to Norfolk all your friends gathered around to offer condolences and you wondered what you had done to deserve such a horrible fate.” (Our Navy, July 1943)

The article mentioned several new places where sailors could find the best means for wholesome diversion, including Fleet Recreation Park, various movie theaters, a YMCA Beach Club, and the Norfolk Center USO Theater, located where the Harrison Opera House is today.

The luxuries listed above were a vast improvement to the area’s previous accommodations. Soon enough, Norfolk became desirable. However, these locations were not the reason why sailors wanted to come to Norfolk during the war. Sailors didn’t necessarily want a slice of the good life; they wanted some semblance of what they craved before the war started. For many, that piece of the past came in the form of baseball. Due to the shortage of stars in the Major Leagues, service teams played the best baseball. For the Navy, the best team in the country called Norfolk’s Naval Training Station their home.

The luxuries listed above were a vast improvement to the area’s previous accommodations. Soon enough, Norfolk became desirable. However, these locations were not the reason why sailors wanted to come to Norfolk during the war. Sailors didn’t necessarily want a slice of the good life; they wanted some semblance of what they craved before the war started. For many, that piece of the past came in the form of baseball. Due to the shortage of stars in the Major Leagues, service teams played the best baseball. For the Navy, the best team in the country called Norfolk’s Naval Training Station their home.

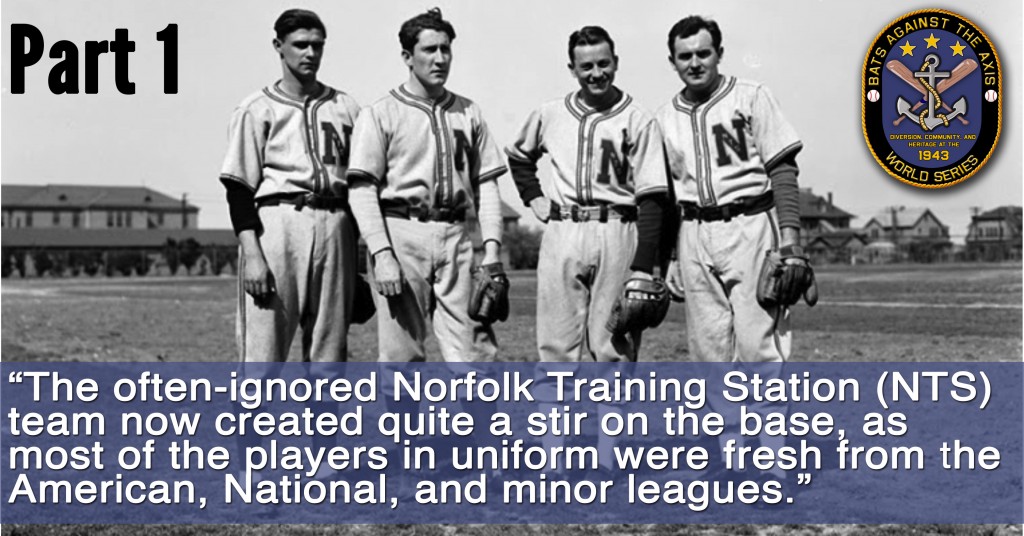

Baseball in the past drew little fanfare at Norfolk’s training station. Clubs at the facility were formed to give sailors a diversion from training. That being said, few paid attention. There was little interest for sailors to see their fellow bluejackets spar on the baseball diamond. Once the war started, however, teams went from amateur to “all star” status virtually overnight. Navy leadership promoted players like Bob Feller to Chief Specialist Athletic to train sailors in physical fitness and play on the station’s league teams. Buzz about the prospect of top-level talent spread quickly in Norfolk:

“The often-ignored Norfolk Training Station (NTS) team now created quite a stir on the base, as most of the players in uniform were fresh from the American, National, and minor leagues.” (Baseball in Norfolk, VA)

Sailors played at NTS Stadium, which would eventually become McClure Field. The field is named after the station’s WWII-era Commanding Officer, Captain Henry McClure. McClure Field was as good a venue as Yankee Stadium during the war years. Unlike other venues around the country, it was closed to the public due to the high security during the war. The brick stadium gave its sailors exclusive access to the best baseball in the country.

Managing the team of stars was Gary Bodie, a Chief Signalman in the U.S. Navy that knew a thing or two about “reading the signs.” Unfortunately, Bodie knew very little about the game. Bob Feller once said Bodie was one of the best coaches he had while in the Navy. Why? According to Feller, Chief Bodie would “stay out of the way and let us play” the majority of the time.

The NTS Blue Jackets, better known as the “NTS Nine,” became a baseball powerhouse. Led by players like Feller and Fred Hutchinson during their 1942 season, the team racked up an impressive 92 wins in 102 games. Unfortunately, the team did not play any major league opponents.

That would change the following season, when top-level talent from major league team and rival Navy ball clubs took to the field to dethrone the Navy’s best baseball team.

Pingback: Bats Against the Axis PART II: King McClure and His Loyal Subjects | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Bats Against the Axis PART III: The Beginning of a Rivalry | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Bats Against the Axis PART IV: 11 Days in September | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Discovering the Norfolk Naval Training Station Bluejackets Through Two Scarce Artifacts | Chevrons and Diamonds