CVL-22 shipmates at their 2009 reunion with the two Captains of the new USS Independence LCS-2. (Photo by: John G. Lambert)

As they shaved in their hotel rooms in eager anticipation of the opening day of the “2009 USS Independence Reunion”, the mirrors reflected back faces of shipmates aged by the passage of over 65 years since, as young men, at war in the Pacific, they had crewed the “Mighty-I.” Father time had aged their bodies, and taken all too many of their friends, but the esprit de corps remained.

Battered by the ongoing erosion of the group’s size as nature took its toll, the notable absence of friends was additionally impacted by the fact that their ship was gone, as were her eight siblings. Not a single example of her historic class of fast light aircraft carrier, that so ably and proudly served our nation in time of dire need, was to have survived as a historical naval museum ship. No … Their ship, the USS Independence CVL-22, lead ship in her class, was sunk by our very own navy.

The ship they had collectively earned Eight Battle Stars upon, endured the pain of the loss of shipmates when torpedoed at Tarawa, reentered the war as our nation’s first dedicated night carrier, survived ravaging typhoons that would send other ships to the bottom, made history and helped establish naval doctrine, supported the invasion of the Philippines (rushing off with Halsey to meet Ozawa in the “Battle of Leyte Gulf”), witnessed the terror of kamikaze attacks off Okinawa, made strikes on Formosa, Indochina, and Japan to name only a brief few of their contributions to the war effort. And their own navy would sink her. Why “their” ship?

The Independence was an expedient of war, at a time of dire need. Not a carrier purpose built from keel up, as the new Essex-class carriers were, the USS Independence was fabricated almost to the main deck as the USS Amsterdam CL-59 (Light Cruiser) prior to 7 December 1941. While the “Battleship Navy” hemorrhaged in the silt of Pearl Harbor after the attack by Japan, a “Stop Work” order was issued at the NYSB yard in Camden NJ. The conversion began from fast light cruiser to fast light aircraft carrier. It was a “make-due” design to rapidly fill the carrier shortage, in what was a seemingly ongoing crisis in the Pacific. Four of our fleet carriers were sunk in 1942, added to a host of other losses, leaving only the overworked Enterprise and Saratoga to help fend off the mighty Japanese fleet, until the new large and complex Essex-class carriers could be floated and made operational for war. As a result, the Independence-class, rushed into the conflict, had its share of shortcomings. By the end of the Pacific war, enough of the Essex- class had been built by our nations amazing wartime production that the CVLs would not for long, fit within the needs and constraints of the downsizing peacetime navy budget.After the surrender of Japan, the CVL-22 was returning to the US from the second of two “Magic Carpet” runs (bringing troops home from the Pacific) when new orders were issued to serve as a target vessel at Bikini Atoll in “Operation Crossroads.” This was to study the effects a new class of weapons, the Atomic Bomb, might have on a fleet of naval vessels. It would further the understanding of the aftereffect of weapons such as “The Gadget” that vaporized the tower at the “Trinity” test site (first detonation of a nuclear device), and the weapons dropped on Japan at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The USS Independence would have “guest of honor” front row seating (more properly…anchorage positioning) close to the primary target vessel USS Nevada.

As only a very brief overview of the massive operation, four blasts would be planned, three carried out:

The first, a test blast (“Queen” – an air burst) with a 2,000-pound conventional fragmentation bomb (dropped from a B-29) would precede the “Able” nuclear device. This was to test instruments and assure readiness for the “Able” test.

The “Able” device (the same type weapon used for “Trinity” and Nagasaki) would also be an air burst. Dropped from a B-29 (“Dave’s Dream”), Major Howard Wood released a MK3A twenty-one kiloton “Fat Man” type bomb on 1 July 1946. It would detonate roughly 520 feet above sea level over the target fleet (roughly 90 vessels) within the atoll’s lagoon. The bomb had drifted off target as it descended, bringing it closer to the Independence than planned. The blinding flash from the detonation was rapidly followed by a searing heat and damaging shockwave that radiated out from the core of a rapidly expanding circular globe of destruction that transitioned into an angry boiling vertical column as it climbed skyward to form a colossal mutant cauliflower shaped mushroom cap as it zoomed toward the stratosphere. More than 10,000 measuring devices including 200 cameras were said to have been utilized to monitor the blast.

Some of the target fleet succumbed to the shock and brutality of “Able” and found refuge on the bottom of the lagoon. The “Mighty-I”, tortured and horribly disfigured by the blast, remained defiantly afloat. But her fate was now sealed.

The blast was approximately 60 degrees to the port (left) side of her stern. The pressure wave from the blast hit her aft and progressed rapidly forward along long high flat side of her mass (along her port side), slightly twisting the hull from the uneven stress as the force progressed rapidly forward. The pressure wave entered the hangar bay and blew upward both aircraft elevators (not to be seen again) and pushed upward and outward on the hangar bay structure. Roll-up steel side curtains (doors) were torn away, and the center of the flight deck structure was displaced vertically, with massive steel cross girders bent upward as much as 6 feet (at their centers) causing the flight deck to take on the “A” shaped appearance of a house roof. Below the waterline, much survived with little effect from the blast in comparison to the damage above, but the vessel was no longer an effective aircraft carrier, and could not have returned fight to an enemy in time of war. The critical boiler rooms were saved from damage from the pressure wave when the four uptakes (rectangular stacks) were folded over, thereby protecting the boiler rooms from damage from over pressurization.

CVL-22 flight deck damage from the “Able” blast (as described above). The ships island and crane are behind and on the right side of the worker. (Photo: Scan by John G. Lambert at NARA San Bruno, CA on the 2015 Independence mission.)

July 25, 1946, was the day of the “Baker” blast. No B-29 would appear to drop the weapon. Instead, the bomb was suspended in the water 90 feet below the lagoon surface beneath LSM-160. Sixty-eight target vessels were at their moorings, and twenty-four smaller vessels were beached inside the atoll. The large test support fleet was roughly 16 miles upwind (outside the atoll) from the device.

Independence was moored only 1390 yards from “Surface Zero.” At 0835 a blinding flash was followed by an expanding globe of water, superheated steam, expanding rapidly upward as it rose thousands of feet high and “at its base a tidal wave of spray and steam rose to smother the fleet”. It was this radioactive spray of water containing a mix of sand, coral from the bottom of the lagoon, mixed with and debris from the nuclear device that would cause more problems than anticipated. “Eight ships including SARATOGA were sunk, eight more seriously damaged”. With far more radioactive contamination than had been anticipated, “For all but 12 target vessels, the target fleet remained too radiologically contaminated to allow more than brief onboard activities”.

USS Independence survived! The planned “Charlie” underwater detonation was canceled due to problems from the “Baker” detonation. An effort was made to effect decontamination procedures and techniques, but the waters of the Bikini Atoll lagoon remained too hot, and use of lagoon water was self-defeating for decontamination efforts. Additionally, the support fleet was also becoming contaminated, so the decision was made to move the “study” vessels to Kwajalein “where they could be serviced in uncontaminated water”.Following initial studies at Kwajalein a number of surviving vessels were returned to Hawaii and the United States for further inspection and studies. Decommissioned at Kwajalein Atoll on 22 August 1946, the “ex-Independence” was towed to San Francisco by ocean tugs USS Hitchiti and USS Pakana, arriving at Hunters Point on 16 June 1947.

At Hunters Point the navy would establish the NRDL – Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, to study the aftereffect of the atomic bombs on the target vessels, and devise methodology for decontamination. Hunters Point was chosen for the location of the NRDL in part due to the close proximity to Berkeley and Stanford Universities, with its plethora of specialized scientists and physicist, that had helped to develop the atomic bomb.

Some machinery was eventually removed from Independence for reuse, with those components not having any levels of radiation to be deemed a hazard, such as its turbines and boiler condensers, which were sent to Point Mugu for use for steam powered generation plants.

With studies completed at the end of 1950, a determination was made to dispose of the “ex-Independence”. It was deemed that the cost and effort to further decontaminate her, compounded by the depressed value of steel scrap at the time made it more practical to tow her out and scuttle the vessel.

The Independence was loaded with radioactive waste “from the NRDL, and other generators”, (the University of California Rad Lab among them).

She would travel under the Golden Gate Bridge to sea once again, this the last time under tow with Task Group 98.5. Independence would be towed out to near the Farallon Islands.

USS Independence being made ready by two tugs to be towed out and scuttled. (Photo from: John G. Lambert supplied courtesy of the US National Park Service, San Francisco CA)

On 26 January 1951, a navy explosives team would place two charges on the keel centerline. At 0952 the charges were fired, and by 1024, having rolled on her port side and sinking by the stern, she would disappear from view leaving only a temporary boil on the surface, seagulls circling overhead.

Without ceremony, the “Mighty-I” had been committed to the floor of the vast Pacific. She settled on the bottom in roughly 2,700 feet of water about 30 miles off Half Moon Bay, California, with her new cargo of radioactive waste.

Eight Battle Stars were hard earned in the great Pacific war. Fifty-two young men were lost, KIA or MIA while serving aboard her, of the over roughly 3,800 that had served aboard or flew from her flight deck. In addition, she had made two “Magic Carpet” runs to bring the troops home from the Pacific, and transported many more aboard during the war.

Hopes of the Reunion Group ever seeing “Their Ship” once again were dashed as she settled upright, reasonably intact, deep and out of sight in the cold grasp of the Pacific.

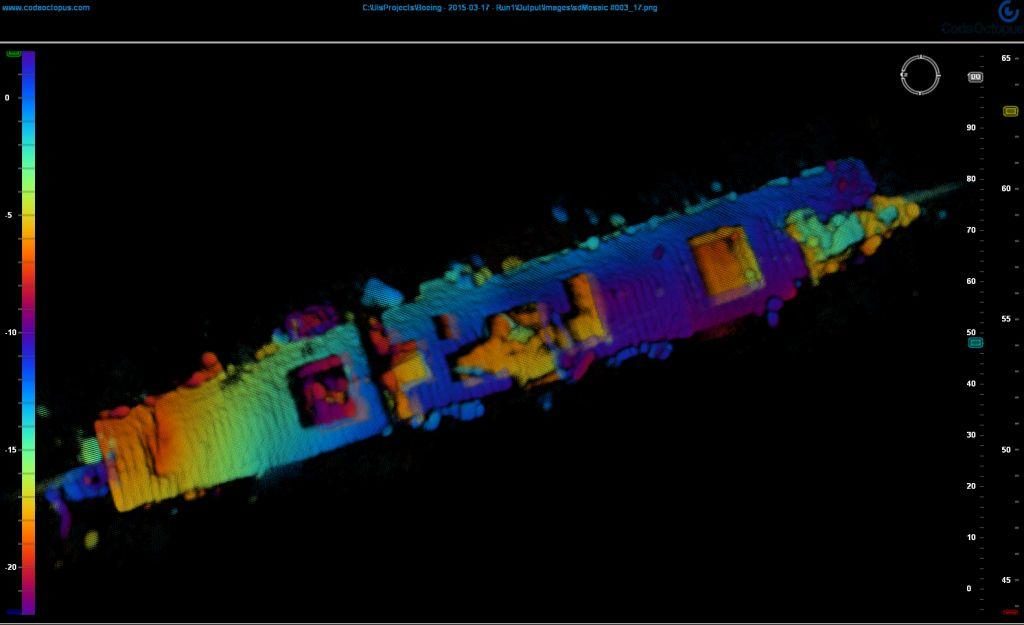

Last year (2015) in a joint mission by the Navy, NOAA, Boeing, and Coda Octopus, the NOAA (Research Vessel) R/V Fulmar towed a yellow unmanned Boeing AUV (Autonomous Underwater Vehicle) called the “Echo Ranger” with a “Coda Octopus” 3D Side Scan Sonar payload 30 miles offshore, to locate, identify and gain a 3D Side Scan Sonar generated image of the former USS Independence CVL-22 to try to ascertain her condition. This August (2016) a renewed effort (headed by Robert Ballard) will further the study of her condition, using different submersibles with video camera technology to obtain a better look at the proud lady, Independence, obscured from view since 1951.

3D Side Scan Sonar image of the Independence on the bottom, roughly 2,700 feet down off Half Moon Bay CA from the joint mission (Navy, NOAA, Boeing, Coda Octopus) in 2015. The bow on the left side. (Image courtesy of Coda Octopus; NOAA)

For the comprehensive and detailed story of the CVL-22, go HERE.

Emmett C. Guderian, Jr

John G. Lambert

Kenneth Lyle Wilson

John G. Lambert

Tom Sesterhenn

John G. Lambert

John G. Lambert

Judith Rodgers

John G. Lambert