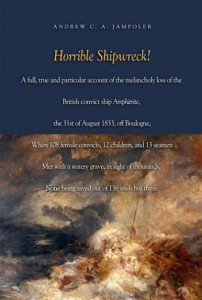

By Andrew C. A. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, (2010).

By Andrew C. A. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, (2010).

Reviewed by Mark Lardas

On August 31, 1833 the convict transport Amphitrite ran aground off Boulogne, France. By dawn of the next day, all aboard, except for three crew members, were dead, drowned when the incoming tide swamped the ship and battered the hull into collapse. In addition to Amphitrite‘s 16-man crew were 108 female convicts and 12 of their children were aboard the ship.

The tragedy was a nine-day’s wonder in post-Regency England. The incident inspired sensational newspaper coverage, a controversial Admiralty investigation, and some truly maudlin poetry. Largely forgotten today, the disaster is the subject of Horrible Shipwreck by Andrew C. A. Jampoler.

Jampoler’s account takes readers through a canvas filled with striking topics and intriguing characters. Amphitrite was transporting prisoners to Australia. Jampoler places transportation into its historical context, explaining why England used Australia as a penal colony, and explaining the mechanics of transportation. He shows how the process was carried out and why Amphitrite was carrying these women on its fatal voyage.

He also places the voyage in its larger context, showing the social structure of Britain in the 1830s. Jampoler also shows how that social structure churned the event into a sensation. The wreck occurred in Boulogne, a town with a large population of expatriate Britons, who witnessed the events. He also shows how one expatriate, John Wilks, a swindler who had left England for France and a career as foreign correspondent, whipped the public into a frenzy with his reports of the wreck. Wilks made the British consul in Bolougne as the villain of the piece.

Jampoler shows the accusation against the consul was fatuous at best and malicious at worst. The British consul lacked authority to force authorities to mount a rescue in a foreign country. Further, mistakes were made by Amphitrite‘s captain, who refused to evacuate the ship after it grounded but before the tide swamped it.

The book has flaws. It has a spattering of minor yet annoying errors. Bellerophon, a ship-of-the-line, is identified by the author as “one of the frigates at Trafalgar.” Jampoler is also somewhat guilty of burying the lede. The actual shipwreck, the focus of the book, is scattered over two chapters and 90 pages. A reader has to re-read those sections of the book to get a focused description of the events as they transpired.

Despite these problems, “Horrible Shipwreck” is a worth reading. It covers a frequently overlooked period of maritime history, and provides a fascinating glimpse at the state of oceangoing sail during the decade when steam began to supplant sail.

Mark Lardas has authored numerous titles on naval historical subjects.