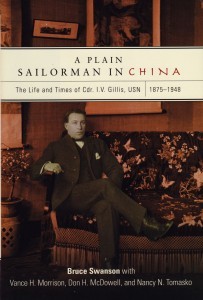

By Bruce Swanson with Vance H. Morrison, Don H. McDowell, and Nancy N. Tomasko, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD. (2012)

By Bruce Swanson with Vance H. Morrison, Don H. McDowell, and Nancy N. Tomasko, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD. (2012)

Reviewed by Diana L. Ahmad, Ph.D.

A Plain Sailorman in China by Bruce Swanson discussed the life of I. V. Gillis, part of a multigenerational Navy family, who became the first United States naval attaché to China. Due to the death of Swanson, Vance Morrison, Don McDowell, and Nancy Tomasko completed the biography recreating the author’s footnotes. Morrison and McDowell polished the chapters Swanson left behind, as well as, with the assistance of Tomasko, wrote the last chapter about Gillis’ life in China from the 1920s until Gillis’ death in China in 1948. The purpose of the biography was to understand Gillis’ success and how he came to be a collector of rare books about China after he retired from the Navy.

A graduate of the Naval Academy in 1894, Gillis served the Navy for nearly thirty years in various capacities, including as a naval attaché in China and Japan and ten years at sea. Although not considered a prestigious position, Gillis served as an engineer, instead of as a line officer aboard several ships, such as Kentucky and Porter. Gillis became well versed in tactics, as well as gunnery maneuvers, successfully making the transition into a modern twentieth-century seaman. His father, Commodore James Henry Gillis, introduced his son to many well-known figures in the Navy, such as Captains Henry Glass and Robley Evans. These associations allowed the younger Gillis access to men of wide experience and intelligence.

Having served valiantly during the Spanish-American War, Gillis was soon transferred to Asia where, in 1902, he combated the Philippine Insurrection and first visited China. Between 1904 and 1907, Gillis worked as the Assistant United States Naval Attaché in Tokyo and soon moved on to intelligence work in China. With a main mission to obtain information about the development of the Chinese naval fleet and its intentions in East Asia, Gillis encountered numerous frustrations with his inability to obtain access to Chinese navy yards and vessels as the Chinese preferred working with the British. He gathered information about the Russian and Japanese fleets during the Russo-Japanese War, and eventually acquired access to periodic briefings by Japanese navy officials.

Gillis returned to sea duty and then became an active participant in the Taft Administration’s Dollar Diplomacy efforts in China. The Navy eventually assigned Gillis to work with Bethlehem Steel Company’s efforts to get the Chinese government to purchase navy vessels from the United States. Much of Gillis’ work in China came after the fall of the Qing Dynasty and during the era of much turbulence under Yuan Shih-k’ai and the Warlord Period prior to the Japanese invasion of much of China between the late 1930s and 1945.

After nearly thirty years in the Navy, Gillis retired in China and married a Chinese woman, purportedly a princess. They adopted two children. During his retirement, he worked as a book collector for Guion Moore Gest, the founder of the Gest Collection of rare books on China, now housed at Princeton University. Following the Japanese capture of Peking, the Japanese interned Gillis and his family to the British Embassy compound for the duration of the war in Asia. After the war and with deteriorating health, Gillis attempted to continue his book collecting for Gest, but as Gest soon died, the efforts came to an end.

The biography is an interesting look at the training of a young officer at the turn-of-the-twentieth century. Much of the book is built around suppositions about Gillis’ efforts and his likely actions. Perhaps because of the death of author Swanson, the book contains numerous instances of things being attributed to Gillis that are only “likely,” “perhaps,” or “apparently” credited to him. The Navy’s records on Gillis put him in certain places at certain times; however, they do not give the specifics of Gillis’ roles making it difficult to completely understand his actions. With that in mind, Gillis likely played active roles in gathering intelligence in Japan and in China. Additionally, the biography features the history of United States-China relations taken only from the American side. There are no histories of China or Japan in the bibliography.

After World War II ended, Gillis returned to his Peking home only to find it in disarray, although not badly damaged. His personal papers and possessions had disappeared impeding a more thorough biography of him. The last chapter provided the best portrait of Gillis’ personality and his dogged determination to complete his tasks, such as collecting books for Guion Gest or information for the Navy.

The book provided excellent photos, helpful maps, and appendices that included Gillis’ family tree and his Record of Naval Service. Gillis threw himself into his assignments, including taking care of modern engines aboard ship, seeking information about Chinese or Japanese naval desires, and collecting tens of thousands of rare volumes of Chinese history. This book provides a valuable contribution to the early history of naval intelligence gathering in East Asia.

Dr. Ahmad teaches at the Missouri University of Science and Technology.