By Captain George Stewart, USN (Retired)

This is the first of three articles that describe my experiences while serving as an engineer aboard commercial tankers in 1961. These articles provide perspective on the different engineering practices between the Navy and Merchant Marine in the post World War II-era. As will become apparent, there were some very sharp differences.I served for five years on active duty in the U.S. Navy after graduating from the Massachusetts Maritime Academy in 1956. My active duty assignments during that period included service as Chief Engineer aboard a Fletcher Class destroyer and as Executive Officer of a minesweeper. Afterwards, I resigned from the Navy for family reasons and look for a shore side career. My purpose in “shipping out” commercially was to gain some hands-on experience and to build up a nest egg for my family. At the time, the pay for a Third Assistant Engineer on a commercial ship was nearly triple what I had made as a naval officer.

It was January 1961. We were living in Long Beach, California. I intended to go down to the Marine Engineers Beneficial Association (MEBA) union hall on a Monday morning to wait for an assignment. However, I received a surprise phone call from the port captain at the Texaco marine office in Wilmington, California on a Saturday evening. He said that an emergency requirement had come up for a Third Assistant Engineer aboard the SS Texaco Minnesota. He asked me if I could be aboard for the 0800 to 1200 AM watch on Sunday morning. I said that I would be there on time.

I packed my bag and my wife drove me down to the Texaco refinery at Wilmington, located between Long Beach and San Pedro in Los Angeles Harbor. The Texaco Minnesota was sitting at the dock. There was a blackboard at the head of the gangway. It indicated that the ship would get underway at 11:30 AM. I asked the gangway attendant where I should sign on. He told me to go up and see the Radio Officer who doubled as the ship’s secretary. I went up and signed the crew register. I went aft and found the Third Engineer’s Cabin and changed into my dungarees. My cabin proved to be very adequate by navy standards. It was larger than the commanding officer’s cabin on my two navy ships. It even had its own bathroom. I posted my Coast Guard license outside my cabin and got ready to go below. I assumed that I would be getting some help when it was time to get the ship underway.

EXPAND FOR T-2 TANKER BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

The T-2 Tanker has to be considered as one of the world’s greatest ships. Along with the Liberty and Victory ships, they formed the backbone of the US Merchant Fleet during and after World War II. The most common variety was the standard United States Maritime Commission type T2-SE-A1. Between 1942 and 1945, 481 were built. The ships were 523’ long and had a full load displacement of 21,800 tons. They had a turbo-electric propulsion system rated at 6000 SHP. Service speed was 14.5 knots. The crew consisted of 38 persons, far less than a comparable naval vessel. A number of modified versions of the T-2 design served as naval fleet oilers during World War II. Some tankers remained in service under the Military Sealift Command well into the mid 1970s. Its naval service crews consisted of over 250 personnel.

In 1961, Texaco operated a fleet of twenty-five coastwise tankers, fourteen of which were T-2s. The coastwise fleet sailed under the U.S. flag because the 1920 Jones Act required that ships carrying cargoes between American ports be registered in the United States (still true today). The bulk of the Texaco coastwise fleet operated out of Port Arthur, Texas, carrying petroleum products of all types to ports in the Northeast. At the time, Texaco only operated two ships on the West Coast, the SS Texaco Minnesota and SS Texaco Delaware. I would end up serving on both ships, as well as the SS Texaco Washington, which operated on the East Coast. Texaco also had tankers in offshore trades. But these were all of Panamanian or Liberian registry.

EXPAND FOR TANKER CREW DESCRIPTION

A major difference between a naval and merchant vessel is the position of the Chief Engineer. Aboard a naval vessel, he is a department head. On a merchant ship, he ranks slightly below the Master. He draws approximately the same pay and operates independently of the Master. In the officer’s mess, the Master sat at the head of the table and the Chief Engineer sat at the opposite end. The Chief Engineer of the Minnesota had many years at sea. Like the Master, he appeared to be in his 60’s. He rarely came to the engine room. In general, the only time I saw him was when I delivered the Engine Room logbook or gave him a lube oil sample at noon. This organization would never work aboard a naval vessel, yet it works successfully on merchant vessels of virtually every maritime nation. On modern automated commercial ships, the Chief Engineer can monitor plant performance directly from a workstation in his stateroom.

The Chief Engineer was a non-watch stander. He had to come up through the ranks in order to achieve his position. The duties of the three assistant engineers aboard Texaco tankers were as follows:

- The First Assistant Engineer was in overall charge of the machinery spaces. He was assigned to the 0400-0800 and 1600-2000 watches. He also came down to the engine room to supervise during maneuvering watches.

- The Second Assistant Engineer was in charge of the fire room. He performed all of the duties assigned to the Oil King on a naval vessel, including responsibility for boiler water chemistry. He stood the midnight to 0400 and 1200-0600 watches in the engine room. His duties did not include responsibility for cargo operations, as these came under cognizance of the Chief Mate.

- The Third Assistant Engineer, which was my assignment, stood the 0800-1200 and 200o-2400 watches. He was required to relieve the First Assistant Engineer around 1700 for a half hour at dinner. Additional duties included the responsibility of maintaining proper levels of lube oil in all equipment plus daily cleaning of the lube oil purifier. He also had that responsibility on gear driven ships without a full time electrician.

The three corresponding deck officers had the same watch rotation as the engineers. The Chief Mate was responsible for all cargo handling and deck seamanship operations. The Second Mate served as the ship’s navigator, while the Third Mate provided assistance to the Chief Mate. Anything outside of our watches was considered overtime, which we would receive extra pay at an increased rate.

I found the door to the engine room and entered the space. It did not look much like a naval engine room. It resembled a shore power station. The space was very roomy and it extended all the way up through the superstructure to a skylight on the uppermost deck. During one trip to San Francisco, I remember seeing the Golden Gate Bridge in the skylight as we passed under. Most of the un-lagged machinery was painted bright green with a red trim instead of the characteristic “navy gray.” The machinery was all running and the space was filled with noise. I went down the ladder to the control platform. There was a night relief crewman on watch. He waved at me and went up the ladder, leaving me alone with all of the operating machinery. There was nobody else in sight. I was in a state of total disorientation.

EXPAND FOR PROPULSION DESCRIPTION

The system was AC-AC drive. Power was supplied from a single steam turbine directly to a 5400 kW 2300 VAC main generator that operated over a speed range of about 900 to 3600 RPM. The generator supplied power to a synchronous motor with a continuous rating of 6000 SHP at 90 RPM. Overload rating was 6600 HP at 93 RPM. It was directly connected to the propeller shaft. Power to the propulsion motor was supplied through manually operated contactors controlled by operating levers at the control cubicle.

Because the system operated at variable voltage and frequency, the main generator could not be used to supply auxiliary power, except when the ship was in port. In a modern integrated electric power system, the main generators are operated at constant speed and voltage, and the power to the propulsion motors is controlled by solid-state frequency changing devices. On systems of this type, the main generators supply both propulsion and ship service power.

Variations in propeller speed were controlled by varying the speed of the main turbine generator by means of the governor control lever at the propulsion control cubicle. The directional rotation of the propeller changed by closing contactors that effectively interchanged two of the three phase leads to the motor stator. Full power was available in both the ahead and astern directions.

A synchronous motor is not self-starting. During the starting period, the turbine was at idle speed. When the motor was ready to be synchronized, as indicated by flickering on the ammeter, DC field excitation was applied to the rotor and the generator excitation was reduced to normal. When the motor was “in step” with the generator, you could increase turbine speed. All steps during the starting process were controlled manually by the engineer. The generator had two poles, while the motor had eighty. This gave a speed ratio of 40:1 between the main turbine and propeller shaft. So the overall effect of the electric propulsion system was to act just like a reverse-reduction gear for the main turbine.

The main turbo generator was driven by a 10 stage single casing steam turbine. The maximum continuous rating was 5400 kW at 3715 rpm, 2370 volts, 3 phase, 62 Hz, 1.0 power factor. The generator was driven directly from the turbine by a solid coupling. The generator was mounted forward of the turbine. It was fully enclosed with a seawater to air cooler mounted on top.

The main thrust bearing, one line shaft bearing, the main feed pumps, and the stern gland was all located in the shaft alley. The stern gland was the old flax packing type you had to keep slacked just enough to keep a small stream of water running continuously to the shaft alley bilges.

Most of the auxiliary equipment in the machinery spaces was electric motor driven. Steam driven auxiliaries included:

- Two turbine driven main feed pumps located below the fire room in the shaft alley.

- One turbine driven forced draft blower that could be lined up to supply combustion air to either boiler. I never saw it used.

- One turbine driven fire & Butterworth pump. The ship operated with a dry fire main. The Butterworth system was used for tank washing.

- Reciprocating auxiliary feed and general service pumps.

- Most major deck machinery. This was in order to facilitate speed control.

Some other significant differences that existed between auxiliary systems aboard commercial and naval ships included:

- Gravity lube oil systems. All main turbo generator and propulsion motor bearings and the main thrust bearing were lubricated from overhead gravity tanks located high in the space. An advantage of this type of system was that it provided sufficient time to stop the propulsion machinery in the event of pressure loss from the main lube oil pumps.

- The deareating feed tanks were located high in the fire room, thereby negating the requirement for feed booster pumps.

- Steam at reduced pressure for feed water heating was provided from the main turbines by way of stop check valves. These were referred to as bleeder or extraction connections. These valves had to be closed during maneuvering and in port operations.

- There was only one distilling plant which was used to make boiler feedwater. Because of the small crew size, it was always possible to obtain sufficient potable water from pierside in order to support the crew.

- The ships burned “Bunker C” heavy fuel oil. A continuous supply of steam was supplied to heating coils located in each of the fuel tanks. The fuel supply to the burners had to be heated to 180° F. Cleaning fuel oil strainers was a very messy job.

- The main condenser seawater inlets were not fitted with scoop injection.

- The steering gear was electro – hydraulic with two motor driven pumps. Bridge control was by means of a hydraulic telemotor. There was no provision for quick changeover between power units. Our practice was to have both units on the line when entering or leaving port. Each power unit was fitted with manually operated valves. The steering gear room was never manned continuously when we were underway. It was only manned when testing the gear prior to getting underway and when placing the standby unit on or taking it off the line when entering or leaving port.

EXPAND FOR TANKER GENERATOR DESCRIPTION

- 400 kW, 440-Volt AC Ship Service Generator.

- 75 kW DC exciter to furnish power to the field circuits of the main generator and motor.

- 55 kW, 120 volt DC generator that supplied power to the excitation bus for the AC generator.

Because of their long stack up length, these generators appeared to be as big as the main generator, at first glance. The gears emitted a high-pitched noise that would have been considered intolerable in naval vessels of later design. But none of us ever wore any type of hearing protection. There was an auxiliary condenser. But it was rarely used. The generators normally exhausted to the main condenser. All normal underway and in port operations were carried out on one auxiliary generator on line. For maneuvering in and out of port, we would bring the second unit up to speed and put it in a standby condition, without putting it on the line. At the end of every trip, we would parallel and shift generators.

On the lower level was a 2300/450-volt transformer for supplying AC power for the cargo and stripping pumps. There were three 200 HP cargo pumps and two 50 HP stripping pumps. The motors were located on the lower level at the forward end of the engine room and they drove the pumps by way of shafts through the bulkhead into the Pump Room, located immediately forward. These pumps were normally supplied with power from the main generator when the ship was in port. When the main generator was used for cargo pumping operations, it had to be brought up to the nearly full rated speed of 3600 RPM with some variation as requested by the cargo pump operator over the telephone. The pumping operations were a cooperative effort by the pump man and the watch engineer who had start-stop and speed control of the motors from a panel on the Main Switchboard. Actual pump speed was controlled by the main turbine generator governor control lever. The watch engineer had to watch the pump motor ammeters which would drop to zero in the event of loss of suction.

None of the three Texaco tankers that I served on had an emergency diesel generator. There was a small 50 kW steam turbo generator in the after starboard corner of the engine room upper level. But I never saw it operated. We were just very careful never to put the lights out. In the event of a dark ship condition, it would have been necessary to supply Diesel fuel to one of the boilers by means of a hand pump.

EXPAND FOR MACHINERY SPACE AND BOILER EXPLANATION

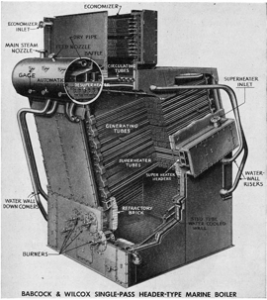

The fire room was located immediately aft of the engine room’s upper level. It was normally manned by a single fireman, even when entering and leaving port. It contained two oil fired sectional header boilers mounted side by side, which provided superheated steam at 435 psi and 725°F to the main and ship service generators. The boilers were provided with Bailey pneumatic automatic combustion control systems. These systems did not come into common use in the U.S. Navy until the early 1960s. Otherwise, the T-2 plants made no more use of automation than naval vessels of that era.

BOILERS

Each boiler was fitted with four oil burners. The burners were not of the wide range type. It was necessary for the fireman to cut them in and out manually in accordance with steam demand. When going from a STOP to a FULL ASTERN bell, for example, the fireman had to run across the firing aisle, cutting in as many as six burners. Boiler water level control was by a single element feed water regulator. The lone fireman was aided by the engineer who controlled acceleration and deceleration rates, and to some extent, the boiler water levels with the main turbine governor lever. This method of boiler control would seem very peculiar to operators of naval boilers of that era.

Unlike the boiler shown in the above illustration, the T-2 boilers were fitted with air preheaters rather than economizers. The preheaters had to be bypassed when maneuvering and during in port operations. The main and auxiliary steam stop valves were of the stop-check type, making it relatively easy to take a boiler off the line when necessary.

On all of the tankers that I served on, there was a placard on the Bailey boiler control board stating “Warning, Anyone Caught Making Unauthorized Adjustments to This System Will be Discharged in the Next Port.”

When I took over the watch, both boilers were on the line. The main turbo generator was idling and one of the two auxiliary generators was on the line supplying electrical power. All of the major auxiliaries were operating and a loud whine permeated the space. The common practice on these ships was to keep the plants steaming all the time, except during shipyard overhauls. As previously discussed, the main turbo generator was used to supply power to the electrically driven main cargo pumps when discharging cargo in port.

I looked for the other members of my watch. About 12 watchstanders would have been required to operate an equivalent naval vessel, but Texaco Minnesota only operated with a 3 man engineering watch consisting of a licensed engineer, fireman, and an oiler. The underway deck watches consisted of a mate, able seaman/helmsman, and an ordinary seaman who acted as lookout. An additional engineer was present during maneuvering operations to keep the “Bell Book”. All logging was accomplished manually.

I went out into the fireroom and found the fireman. He said that everything was functioning normally and was going up to use the toilet. The idea of leaving two boilers steaming unattended was foreign to me, but I did not question it. I finally located the oiler in the engineroom. His functions were to assist the engineer in the operation of the engine room. He was a Cuban and did not speak very good English. Over at the corner of the switchboard, there was an imposing looking control desk with some large levers sticking out of it. The machinery was controlled from this location in response to orders received over the engine order telegraph from the bridge. The control levers were very similar in appearance to those aboard the turboelectric destroyer escorts and conventional diesel submarines of that era. Since I knew that the watch engineer normally operated the controls himself, I asked the oiler how to work the levers. His answers were half in English and half in Spanish. I began to think that I had bitten off more than I could chew. I hoped that someone else would show up in time to help me get the ship underway at 11:30.

At about 11AM, the phone rang and I answered it. A voice at the other end asked who this was. When I responded he hurriedly hung up and I heard the door slam up above. A rather harassed looking individual arrived on the floorplates and demanded to know what I was doing down there. When I responded that I was hired by the port captain the night before, his response was, “Why the hell didn’t he tell me you were here?” Obviously, I had no satisfactory answer to this question. When he asked me if I had ever steamed a turboelectric ship before, my response was, of course, negative. He introduced himself as the First Assistant Engineer. He then pointed out that we were getting underway at 11:30 and had better get to work.

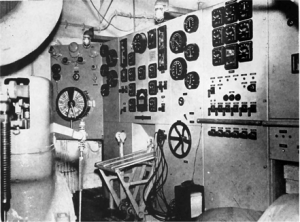

The following illustration shows a General Electric control cubicle on a T-2 tanker. The main turbo generator governor can be seen at the left side of the illustration.

To get underway, it was only necessary to start up the standby ship service generator, go aft to the steering gear room and start up test the electro hydraulic steering gear, test the engine order telegraph, and close one switch on the control panel. The whistle blew overhead, the telegraph swung to “STAND BY,” and we were ready to start maneuvering.

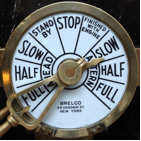

The engine order telegraph had different markings than those aboard naval Vessels as shown in the following illustration.

The “STAND BY” position was used whenever the bridge was ready to start maneuvering, both when entering and leaving port. The bridge could also ring up a “dead slow” bell by ringing the “SLOW” bell twice. There was no revolution telegraph. All the engineer had to remember was 20, 40, 60, and 80 RPM.

I thought it was rather peculiar that we did not test the propulsion system prior to getting underway. When asked, the First’s response was, “How would you know that it is going to work the next time?”

The telegraph swung to “HALF ASTERN”. The First threw a control lever to the “START ASTERN” position. There was a thump and the main motor started. He moved the lever to the “RUN ASTERN” position. He grasped the main turbine governor control lever until the engine made a satisfactory whine. He then turned the operation over to me.

I have to confess that I was not very good. The control levers took a great deal of effort to operate and I tended to overshoot the desired position, in the process creating lightning bolts behind the switchboard. After a number of maneuvers, we were finally underway with the propeller humming away at about 90 RPM. About that time, the Second Engineer arrived on the floorplates to relieve me. On the way up to lunch, the First took me in and introduced me to the Chief Engineer who was in his cabin. It was the first time that I had seen him.

The First Engineer became my mentor. He was extremely dedicated and driven, but I can say that he broke me in quite well. He taught me how to operate every piece of machinery in the engineering plant. I was required to trace out and sketch every piping system and At sea and in port, I was required to take a complete tour of the machinery spaces, including the steering gear room prior to taking over the watch. Unless the ship was in a maneuvering situation or fog, I did not have to remain on the control platform at sea. I spent most of my watches performing maintenance tasks or working in the machine shop leaving the oiler alone on the throttle platform. I had to be there at the beginning, mid point, and end of each watch while the Oiler made his rounds and took readings.

All licensed engineers were required to be proficient in lathe operation. This was a carry over from the days of reciprocating steam engines where the crew was required to make their own engine parts. One of my duties was care of the lube oil systems including daily cleaning of the purifier and strainers and ensuring that proper oil levels were maintained in all equipment. I was also responsible for any required repairs to the lagging and insulation. In the process, I was probably exposed to plenty of asbestos. I was also required to blow boiler tubes immediately prior to or after leaving port. Many people would have considered it to be a boring routine, but it wasn’t too bad once you got used to it. In port, we did not break sea watches, as we were always engaged in loading or unloading cargo. We did get some relief by night crewmen in our homeport.

I found that civilian crews tended to follow much stricter operating practices than those aboard naval ships. But they were not as good as U.S. Navy crews at cold plant lightoff and shutdown due to the fact that the plants were rarely shut down except during a shipyard overhaul period. From this standpoint, I found my previous naval experience quite valuable. In addition, none of the crewmembers were required to conduct U.S. Navy-type engine casualty control exercises. There were no written casualty control procedures. It was left up to the watch engineer as to determine how to control casualties with assistance from the Chief or First Assistant Engineer. This sounds like a peculiar way to do things to those accustomed to naval procedures, but we managed to make it work quite well. We had no blackouts during my time at sea aboard these ships.

There was little in the line of social life on the ship. Turnaround times were kept to an absolute minimum, as the ship only made money for the company when it was at sea or loading and discharging cargo in port. The ship rarely spent more than 12 to 16 hours in port at a time. The only way that this routine was made bearable was by liberal vacations. You accumulated 1/2 days vacation for every day worked. The normal rotation was 6 months on and 3 months off. A new officer like me had to start by working as a vacation relief. After one year of service, you obtained regular status.

As I previously mentioned, the ship was primarily engaged in delivering fuel oil to paper mills in the northwest. Much of our time was spent maneuvering in and out of port and conducting dockside loading or unloading of cargo. I remember visiting Hoquiam, Aberdeen, Port Townsend, Everett, Port Angeles, and Portland, among others. Our itinerary resulted in a return to our homeport of Wilmington every 2 weeks, approximately. Just prior to arrival, I would visit the Radio Officer (Who doubled as the ship’s secretary) and draw whatever pay I had accumulated in the form of cash. I would then deliver nearly all of it to my wife on arrival. She never knew exactly how much she was going to get. By 1961 standards, it was always fairly substantial.

After about 3 months on the Minnesota, the regular 3rd Engineer was returning from vacation. I made a good impression on the ship, so the company decided that it was in their interest to keep me working. I was asked to take another three-month assignment as a relief 3rd Engineer aboard the SS Texaco Delaware. This was the only other Texaco ship that operated on the West Coast. I was warned by the people on the Minnesota to expect a very different experience. That would prove to be very true as described in the second article in this series. Texaco Minnesota was “Jumboized” by addition of a 72’ midship section in 1964. The ship was finally scrapped in 1990.

George W. Stewart is a retired US Navy Captain. He is a 1956 graduate of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. During his 30 year naval career, he held two ship commands and served a total of 8 years on naval material inspection boards, during which he conducted trials and inspections aboard over 200 naval vessels. Since his retirement from active naval service in 1986 he has been employed in the ship design industry where he has specialized in the development of concept designs of propulsion and powering systems, some of which have entered active service. He currently holds the title of Chief Marine Engineer at Marine Design Dynamics.

Andrew S. Niemyer

Pingback: Shipping Out: My Experiences on a Commercial Tanker (Part II) | Naval Historical Foundation

John Rochelle

George W. Stewart

Francisco Conde

PEGGY YUNG

Admin

les wilson

Lester Wilson

Jack Fallon

George W. Stewart

Andrew Schwarz

George W. Stewart

Ray Hooper

Andrew Schwarz

Timothy Lewis O'Neil

Alan hanson

Lester Wilson

Milt Bell

Admin

Bob Liddell

Henrik Björk

john bengtson

Ted Farrell

John Bengtson

Teena Boggs

Richard Ryder

Chris Sweeney

A.A. Visser