“With rare exceptions Alfred disapproves of everything he sees when on shore leave, although he does not object to others enjoying themselves.”

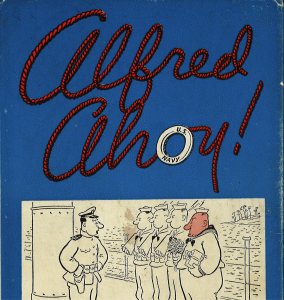

The Naval Historical Foundation received a few “rare editions” from a box of donated books last month. Included in the list of usual naval history titles were two compendiums of World War II-era cartoons. Readers will be familiar with the first volume, a collection of 115 illustrations of “The Sad Sack,” a humorous Army cartoon that appeared in Yank Magazine throughout the war. The other lesser-known title is a first printing of Foster Humfreville’s Alfred, Ahoy! This collection of “choice gags” features the character of Alfred, “one of the best loved goofs in the cartoon world.” Alfred the sailor appears in a variety of humorous situations both on shore and afloat. For many at the time, however, the droopy-faced hero of the cartoon became a major topic of conversation during the war. According to Collier’s Weekly Cartoon Editor Gurney Williams, sailors “began to clamor” for Alfred comics after their first appearance in the magazine. For some, Alfred became a household name and a source of well-needed diversion during a troubling time.

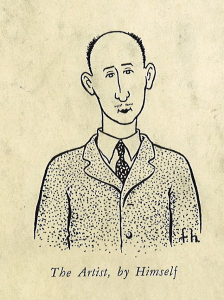

Foster Humfreville is surely one of the obscure cartoonists of the era. He is not listed among Collier’s top list of cartoonists (Joseph Barbera, Bill Mauldin, Hank Ketcham, etc.), yet his cartoons were popular enough during the Second World War to warrant a collection. According to a biography of the artist, Humfreville left the banking industry to pursue art during the depression, eventually moving to New York City to become a sculptor and artist. He is best known during this time for a WPA public service poster produced in 1937 for the New York Department of Corrections titled, “Shame May Be Fatal.” In 1941, he sold his first comic to Collier’s and quickly became an artist for the weekly magazine.

Foster Humfreville is surely one of the obscure cartoonists of the era. He is not listed among Collier’s top list of cartoonists (Joseph Barbera, Bill Mauldin, Hank Ketcham, etc.), yet his cartoons were popular enough during the Second World War to warrant a collection. According to a biography of the artist, Humfreville left the banking industry to pursue art during the depression, eventually moving to New York City to become a sculptor and artist. He is best known during this time for a WPA public service poster produced in 1937 for the New York Department of Corrections titled, “Shame May Be Fatal.” In 1941, he sold his first comic to Collier’s and quickly became an artist for the weekly magazine.

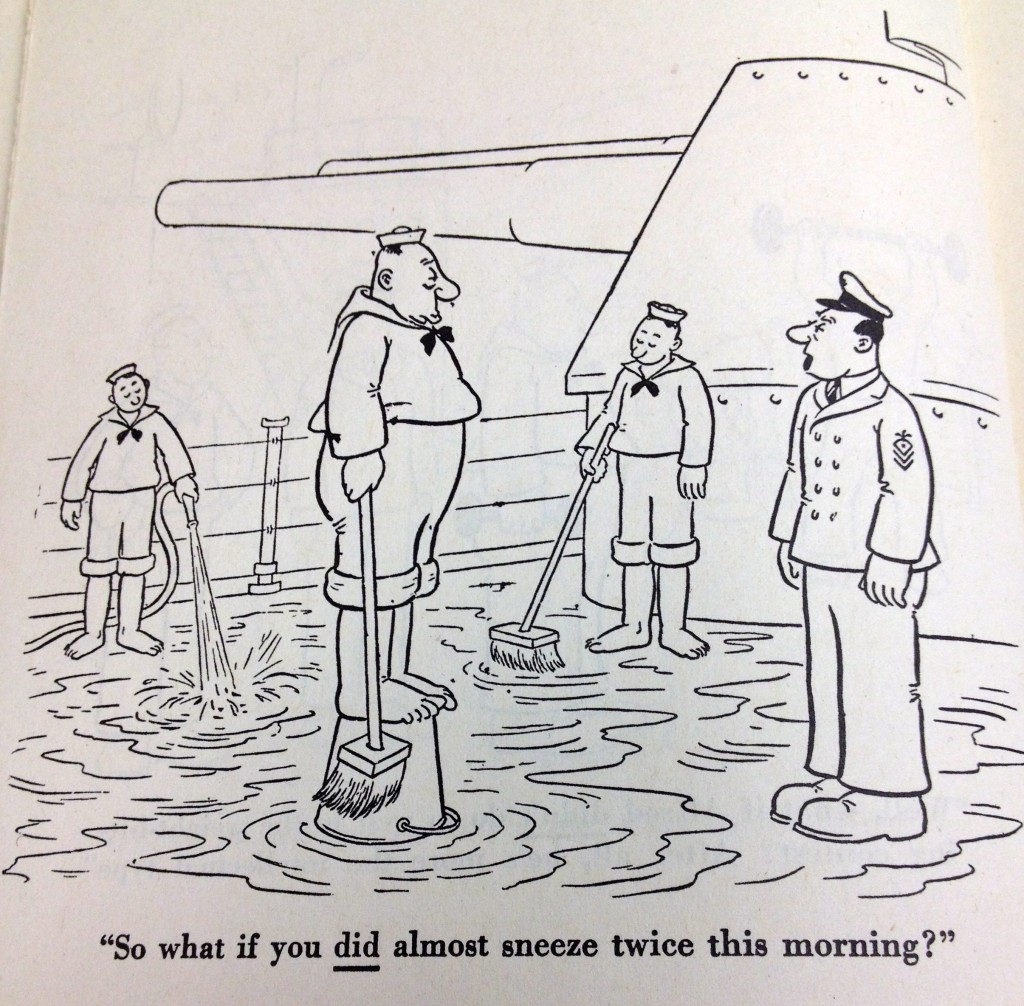

Humfreville’s Alfred cartoons are the perfect blend of intelligent humor and Navy life. The cartoons also capture the frantic nature of naval warfare in the 1940s: relative monotony punctuated by fierce and deadly combat. Throughout the comic strip series, Alfred is depicted performing a variety of humdrum tasks such as swabbing the deck, loading ammunition, conducting rifle drills, or sending semaphore flag signals.

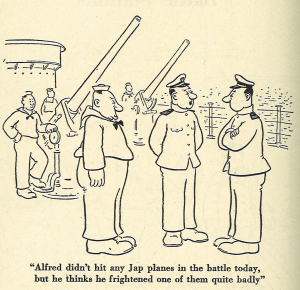

Whatever situation Alfred found himself him, his facial expression remained the same. The indifferent and judgmental gaze of Alfred forces readers to wonder what the sailor is thinking. Humfreville himself admitted he knew very little about the Navy. Most of his ideas and inspiration for his Collier’s comics came from conversations with sailors about shipboard Navy life. Some cartoons take a completely literal and likely cryptic explanation of the image shown. It’s almost philosophical. Take, for instance, the illustration below:

Whatever situation Alfred found himself him, his facial expression remained the same. The indifferent and judgmental gaze of Alfred forces readers to wonder what the sailor is thinking. Humfreville himself admitted he knew very little about the Navy. Most of his ideas and inspiration for his Collier’s comics came from conversations with sailors about shipboard Navy life. Some cartoons take a completely literal and likely cryptic explanation of the image shown. It’s almost philosophical. Take, for instance, the illustration below:

Alfred is never the one doing the talking. It seems that the artist’s intention was to always show Alfred’s “fine disdain for rank and discipline and disregard for danger” through his silence and carefree demeanor. After all, Alfred is described quite clearly as a mere “sensitive, simple-minded gob.” His profile closely resembles Alfred Hitchock’s signature pose. Perhaps there is more. Reading the cartoons at “face-value” only lends itself to a small portion of its interpretation. Like all good art, there are layers of meaning. There must be more to this simpleton.

In the introduction to the collection, famed political reporter Walter Davenport gives readers a “somewhat incredible,” yet altogether fake, biography of Alfred. His description of Alfred is at first as hilarious as the cartoons themselves. But then you read further. Clearly, you start to see an agenda and message forming from the scrawled images of Alfred and his antics. His description of Alfred and his father share some insight into the mind of the cartoonist, who considered himself the “foster father” of the character:

“Actually Alfred and his father were protesting against Japanese aggression, against the Jap violation of this important fact of life. As you study Mr. Humfreville’s drawings all this will become very clear.”

Humfreville moved back to his home state of California in the summer of 1942. His message is a clear nod to his disagreement with the internment of Japanese in California during the war.

Davenport also discusses the character’s motivation for enlisting in the Navy. Alfred enlists in the Navy under the idea that his actions will be motivated by four principles his father taught him. Among other instructions like avoiding enthusiasm and “letting others do the thinking,” the final principle is particularly moving. He simply states:

“People will always be trying to make you do something you don’t want to do. Let on you don’t hear them.”

Even a dim-witted gob can get philosophical from time to time.

Victoria Parret

Linda Erickson Suazo

Allan Holtz