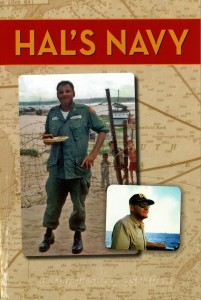

By Cdr. Harold Sacks, USN (Ret.), Park Press, Norfolk, VA. (2013)

By Cdr. Harold Sacks, USN (Ret.), Park Press, Norfolk, VA. (2013)

Reviewed by Charles H. Bogart

Cdr. Sacks has written a highly readable book about his service in the United States Navy from 1952 to 1972. He spent most of his service in the Navy on a destroyer or serving in the intelligence community. While the book contains a few sea stories (his visit to Onassis’s mega-yacht Christina being the best of the lot), the author concerns himself primarily with telling the story of what it was like to be a naval officer during the early years of the Cold War. The author saw combat in Korea and Vietnam.

Hal’s Navy is the story of one man progressing from the newest officer on board USS Owen (DD 536) as it was preparing for deployment to Korea to that of commanding officer of USS Steinaker (DD 863) during operations on the gun line along the shore of Vietnam. Between these two events, he served tours of duty onboard USS Des Moines (CA 134), USS Blandy (DD 937), USS Davis (DD 937), and USS Gyatt (DD 712). Woven throughout the book are details concerning his family and his endeavors to ensure that practicing members of the Jewish religion were able to receive spiritual comfort from members of their own faith. During his tour in Vietnam, he established a Jewish religious center in Saigon and started the paperwork to have a rabbi deployed to Vietnam.

While Commander Sacks’ tales of sea duty are fascinating, what the reviewer found most interesting were his accounts of shore duty with the intelligence community, particularly his service with the Navy Scientific and Technical Intelligence Center (STIC) located in Washington, D.C. on the grounds of the Naval Observatory.

The story of his service at Gitmo is one of the few accounts that have been written about life at this base. He gives the reader insight as to what life was like there as the Batista government fell and Castro seized power. Equally fascinating is his tale of serving under Rear Admiral John D. Buckeley. As one reads this account, one quickly grasps why Buckeley was such a leader of men.

I am sure that many other career naval men have wrestled with the decision the author agonized over—to stay in or leave the Navy. The author knew he was being groomed for advancement to Captain, but he had a family that had established strong emotional ties in the Norfolk area. Faced with three choices: uproot the family, commute between Washington and Norfolk, or change careers, he opted to put his family first and regretfully left the Navy.

The book is worth reading by anyone interested in the U.S. Navy during the 1950’s and 1960’s. I believe that any person starting a career in the Navy would be well served by reading this book. No matter what assignment Cdr. Sacks was given in the Navy, he found some way to use the experience he gained to make himself a better man. Autobiographies like this will provide a nice insight into the U.S. Navy during the Cold War period for historians researching the U.S. Navy fifty years from now.

Charles H. Bogart is a frequent contributor to Naval History Book Reviews.