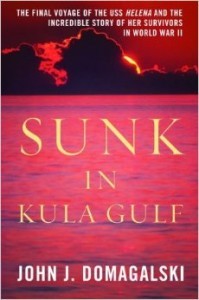

By John J. Domagalski, Potomac Books, Washington, DC (2012)

By John J. Domagalski, Potomac Books, Washington, DC (2012)

Reviewed by John Grady

The greatest strength of John Domagalski’s Sunk in Kula Gulf lies in the interviews he conducted with survivors of the cruiser Helena’s sinking after it was torpedoed early 6 July 1943. While I found the first few chapters’ routine, the story picks up speed and humanity from Chapter 7 on. The remaining chapters details exactly what happened to the 1,200-man crew.

The survivors ended up in three distinct groups after the “Abandon ship” order was given. Two destroyers picked up the first and largest group of more than 700 men as the fight with the Japanese in the Solomon Islands roared on. One of the sailors, Robert Howe, remembered thinking that the treatment he received aboard Nicholas was the same as what Helena’s crew did for survivors of Wasp; dressing their wounds, setting broken bones, and salving their burns. Officers of the cramped Radford knew that they needed to move survivors to the deepest parts of the ship as the destroyer moved quickly back into the fight with its 5-inch guns firing.

The second group of 88 sailors and officers tried to stay together in three lifeboats. They made it safely to a nearby island waiting and to be picked up the next day. The third group, clinging to whatever they could to stay alive, was pushed by strong currents away from the sinking vessel. They were adrift under a tropical sun for days, covered in oil. Jim Layton’s hope for a rescue ship faded with each hour. “I don’t remember anyone else displaying a lot of fear,” he said. “Maybe we more or less accepted what was happening.” The survivors were drifting closer and closer to the Japanese-held island Vella Lavella.

The Japanese indigenous peoples were not the only people on the island when the Americans came ashore at scattered locations. There were also missionaries and Australian and New Zealand coast watchers monitoring what the Japanese were doing both ashore and afloat. Tension built as the Allies rounded up the survivors on the shore and hurried the Americans to safety into three secure hideouts. They also had to dispose of the tell-tale rafts that littered the shore.

Domagalski does a fine job detailing how these men lived for the next eight days and also how they were rescued. It is a gripping reading and the “incredible story” that the subtitle promises.

Grady is a volunteer with the NHF’s oral history program.