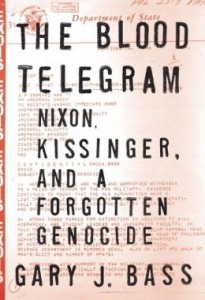

By Gary J. Bass, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY (2013)

By Gary J. Bass, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY (2013)

Reviewed by LTJG J. Scott Shaffer USN

With the U.S. Navy increasing their presence in the Asia theatre under Pacific Pivot, well-researched narratives covering the history of major regional powers remain in high demand. Gary Bass’s book The Blood Telegraph: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide provides great insight into the circumstances surrounding Bangladesh’s independence and the roles played by the United States, Russia, China, India, and Pakistan. Using recently de-classified White House records along with reporting of crisis, Bass ties together how leaders from those countries reacted in the outbreak of hostilities resulting in the Fourteen Day War in 1971.

While discussing the relationships between India, Pakistan, and the United States through the Kennedy and Johnson years, the narrative focuses on the actions taken by the Nixon Administration and their support of Pakistan’s military dictator General Agha Muhammad “Yahya” Khan. After the results of the 1970’s election in Pakistan, Yahya ordered troops into Eastern Pakistan to squash Bangladeshi rebels. As the title suggests (although named for the American consul general in East Pakistan, Archer Blood), the troop movement resulted in a brutal genocide committed by Pakistani troops against the population. Bass describes the atrocities committed Pakistani soldiers from the shelling of universities, burning of homes, and the specific targeting of East Pakistani Hindus. The crisis not only wrecked the lands and population of Bangladesh, but also spread to India. Struggling with their own internal challenges, including poverty and clashing religions, the government faced a large influx of Hindu refugees. While the reader will begin to understand the rational for India’s military action against Pakistan, Bass, critical of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, highlights her own personal motives for war. He writes detailed accounts of the training provided by India’s military to Bangladeshi rebels and the actions taken by the Indian Navy in the Bay of Bengal. Because of the situation, Gandhi was not the only politician using the crisis for political gains.

The majority of the book narrates the Nixon Administration’s inaction. Despite reports from the American consul and the state department, Nixon and Kissinger refused to take any position against Yahya. Bass challenges their continued support in providing military arms to Pakistan despite reports of an alleged genocide. According to the author, Yahya’s ability to communicate to the Chinese, culminating in the President’s visit to China, remained the primary factor driving Nixon. While the novel provides a brief history of the poor relationship between India and the United States during the Cold War, the strong support of Pakistan and hostile view of India by held Nixon ultimately drove Prime Minister Gandhi closer the Soviet Union.

Bass criticizes Nixon and Kissinger’s support of a military dictatorship in Pakistan while working against a democratically elected government in India charging that they share some of the responsibility for the violence that occurred in Bangladesh. His conclusion is understandable considering his previous works covering humanitarian interventions in his last two novels; yet, he fails to consider the Kennan view of Americans leaders during the Cold War. While Nixon and Kissinger will admit they supported Pakistan to show China their loyalty during the crisis, their actions were in keeping with a much larger view of diplomacy as held by any other President during the Cold War.[1] To Nixon, the conflict represented Pakistan, an ally of the United States, versus India, a “client” of the Soviet Union.[2] As Nixon stated in a foreign policy speech prior to the 1960’s election regarding South America, “The policy of maintaining diplomatic relations with South American nations which have various forms of dictatorial governments is not a new one…this policy does not weaken in any way our own devotion to guarantees [of liberties]. [Latin countries] would resent nothing more than for the United States to try and tell them what government they must have.”[3] To Nixon, the crisis was a domestic matter for Pakistan to act independently without foreign interference.

Noting that the support of Pakistan soured American-Indian relations until the Clinton administration, the author suggests that Nixon could have used the crisis to develop a closer relationship with India. Instead, Nixon ordered the Enterprise Strike Group into the Bay of Bengal and used the United Nations to pressure India to seize hostilities against Pakistan. However, in an Op-Ed written by Henry Kissinger in 2006, the former secretary stated that any partnership with India during the Cold War would have jeopardized India’s own security interest by “risk[ing] the hostility of the other nuclear superpower, only a few hundred miles [away]” (i.e. the Soviet Union).[4] With globalization and the world economy, India can no longer afford its “Cold War attitude of aloofness” or it will risk being left out as an important regional power.[5] Thus, today the United States and India have the opportunity to create a partnership through trade and promoting regional security.[6]

Despite some of the impressions left by the author, The Blood Telegram provides readers a thorough yet interesting read covering an overlooked event in history. Bass’s writing style keeps the reader engaged and presents a complex situation into an organized historical account of the actions taken by the region’s most influential nations. As the book provides a greater understanding to anyone interested in the history of Southeast Asia, it should be read at the strategic down to the tactical actors of the Pacific Pivot initiative.

LT J. Scott Shaffer is the Fire Control Officer onboard USS Cape St. George (CG-71). He previously served as the Brigade Honor Chair at the United States Naval Academy from the 2009 to 2010 academic year and onboard USS Curtis Wilbur (DDG 54) as First Lieutenant. He hold a Bachelor’s of Science in Political Science from the U.S. Naval Academy and is a graduate student at Arizona State University.

[1] Nixon, R.M. (1977). Interviewed by David Frost [Audio recording]. The Nixon Interviews with David Frost. “Nixon and the World.” R.A. Inbows Ltd.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Nixon, Richard M. The Challenges We Face. (New York, New York: Popular Library, October, 1961), 91.

[4] Kissinger, Henry. “Working With India: America and Asia Stand to Gain From This New Relationship.” The Washington Post (March 20, 2006).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.