NHF Historian Dr. David Winkler (at the podium) addresses the U.S. and Russian Navy delegations during concluding ceremonies of the 40th Annual Incidents at Sea Agreement Review that was held at the Naval Observatory. U.S. Navy Photo.

NHF Staff

Last Friday’s SU-27 barrel roll of USAF RC-135 and earlier buzzings of USN Destroyer are rare hiccups in 44 year INCSEA accord.

The Incidents at Sea Agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union had only been signed a year earlier in Moscow by Secretary of the Navy John W. Warner and Admiral of the Fleet Sergei Gorshkov on behalf of their respective presidents. One of the provisions called for an annual review meeting to be hosted by each nation on a rotating basis.

The first such review was set to be held in Washington beginning on May 14, 1973. Selected to head the American delegation Vice Admiral J.P. “Blackie” Weinel understood that the first review would set a foundation for building trust with his Soviet counterparts. Meeting with members of his delegation Weinel exclaimed:

“No posturing, no bragging, and no looking down our noses at the Russians. Take no interest whatsoever in any kinds of secrets. Don’t even act like you’re trying to find anything out, because we are not on any intelligence missions. I don’t give a damn if they were building seventeen aircraft carriers. That’s not what we are here for. Establish give and take with your counterparts. Don’t make it one way. Be able to listen as much as you talk. Admit to yourselves that the Russians could be right and have a better mousetrap than we have. Always focus on the bottom line, which is we both see the foolishness of the games of chicken and we need to knock it off. And finally: Be absolutely, completely honest with them!”

With no direct flights between Moscow and Washington in 1973, the Russians flew into New York’s Kennedy Airport and transferred to National Airlines for the short evening hop to Washington. Unfortunately, though the Russians made the connection, their luggage did not!

The next morning, Vice Admiral Weinel arrived early at the Washington Hilton to meet with his counterpart, First Deputy Chief of the Main Navy Staff, Admiral Vladimir N. Alekseyev. Still donning the clothes he wore the previous day, Weinel could discern that Alekseyev was not happy.

Weinel recalled the first thing Alekseyev said was:

“Where the hell is my luggage?”

For some reason that he later confessed that he never understood Weinel responded:

“We didn’t realize you had as much luggage as you had. We haven’t finished searching through your luggage yet but we should be at about 10 o’clock this morning.”

Alekseyev didn’t bat an eye and turned to his interpreter:

“Well, I’m going to have ham, eggs, potatoes, and a pot of coffee.”

From then on while the Russians were in Washington, Alekseyev would tell listeners:

“What an honest man Admiral Weinel is. I completely trust him!”

With a trusting rapport established under false pretenses, the first annual review produced constructive exchanges that led to a protocol that extended the 1972 accord to include the merchant ships of both sides. From there on, naval leaders from both nations continued to annually meet to frankly discuss the interactions of their respective fleets. During the first decade of the accord, the number of incidents dropped off substantially from the pre-INCSEA timeframe.

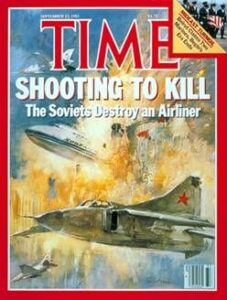

Then, after the Soviet shoot-down of KAL 007 on September 1, 1983, west of Sakhalin Island, the Soviet Navy attempted to interfere with American and Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force recovery operations. Rear Admiral Ronald Kurth recalled:

“It was a very severe challenge to the agreement and intrusion on the part of the Soviet Navy.”

Using the method prescribed in the agreement, the United States protested the harassment. The Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Sylvester R. Foley summed up what happened:

“The Soviets gave us trouble and hassled us and we said ‘if the Incidents at Sea Agreement means anything, cut it out,’ and they did.”

In the aftermath of the Sea of Japan incidents, Rear Admiral Kurth found the Soviets very conciliatory at the 1984 annual review:

“The Soviets really, really did everything possible to preserve the agreement and reestablish confidence. They handled their conduct in the Sea of Japan very openly, and we did, indeed, reestablish confidence.”

Explaining the Soviet change of face, a veteran of the U.S. delegation, Captain Edward J. Melanson observed:

“While we saw it as a technical agreement, the Soviets, particularly the Soviet Navy, saw it more in a political context of an agreement that kind of set their service apart from the rest – as they were dealing on a bilateral basis with United States Navy.”

This observation certainly could have been seconded by Vice Admiral Weinel. A year following the lost luggage incident that led to the first of the series productive reviews, Weinel was greeted by Admiral Alekseyev as he stepped off his airplane in Moscow. As the two men exchanged pleasantries, the American could not but help notice nearly everyone in the Russian reception committee checking their watches. Weinel recalled “in some phenomenally short time like four minutes sixteen seconds” the luggage arrived and Alekseyev proudly announced:

“You can pick up your luggage now!”

A staff historian, Dr. Winkler’s Ph.D. dissertation on the Incidents at Sea Agreement was published under the title Cold War at Sea: High-Seas Confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union by the Naval Institute Press in 2000.