By: Kyle Nappi

For years, blockbuster movies have illuminated the feats of the warring sailors from World War II’s European Theater of Operations: The Enemy Below (1957), Das Boot (1981), and U-571 (2000) to name a few. This year –pending COVID-19 – Tom Hanks will unveil Greyhound, a war epic set during the Battle of the Atlantic. To some, these movies offer a glimpse into the perils of life at sea during wartime. Others struggle with historical inaccuracies. Driven by a curiosity to better understand the human side of war, and set aside dramatized war movie stereotypes, I sought to learn from the aging combatants themselves.

Over the span of nearly a decade, and with the investment in more man-hours and postage costs than I care to remember, I amassed close to 4,500 individual biographical accounts from surviving military veterans of multiple nationalities. Chief among them were the rapidly fading octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians from World War II, ranging from infantrymen at Omaha Beach to combat photographers at Tarawa.

Now armed with first hand insights into the American experience of World War II, I sought perspectives from our Commonwealth and Soviet allies. Concurrent with this effort was a bold step to turn my gaze to the vanquished combatants. Ultimately, I gained a new and well-rounded perspectives through the dichotomies created from several hundred veterans of the Axis Powers: German tank commanders at Normandy, Italian human torpedoes in the Mediterranean, and young Japanese aviators training as kamikaze pilots.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of Germany’s surrender during World War II – and in anticipation of the release of Greyhound this year – I wanted to offer some anecdotes I gathered from surviving veterans of Germany’s U-boat force…the last wolves.

For some, the Kriegsmarine was simply an extension of their earlier nautical pursuits.

“At the age of 12 I started sailing on the Wannsee near Berlin, then with big boats on the North Sea, Baltic Sea and Mediterranean,” recalled Jürgen Oesten. “Then I went to the Navy.” Four months following Hitler’s ascent as German Chancellor, Oesten joined the Reichsmarine (the Kriesgmarine’s predecessor). “Before the war, I was second in command aboard U-20, a small boat.”

In August 1939, Oesten had his own boat and quickly distinguished himself as a prominent and decorated U-boat captain with over 100,000 tons sunk in the course of his thirteen patrols totaling 579 days at sea. Despite these accomplishments, Oesten spoke rather modestly in regards to his wartime years. “During the first year of the war, I was in command of U-61 working [the] British east and west coast[s].” In these waters, Oesten’s crew torpedoed five ships. “Next was U-106 [attacking] North Atlantic and South Atlantic convoys.”

There, Oesten’s crew sank ten ships and scored a damaging hit on a British Royal Navy battleship off the West African coast.

Perhaps most interesting was Oesten’s third command. “Later on, I had U-861 in the Indian Ocean.” Better known as the Monsun Gruppe, this unique U-boat wolfpack operated in the waters near Southeast Asia, the only theater in which German and Japanese forces fought together during the war. Of the Kriegsmarine’s fifty-seven Monsun Gruppe U-boats, only sixteen survived the voyage from Europe to Southeast Asia. Of these sixteen, Oesten’s U-861 was one of six that survived the treacherous round-trip voyage back to Europe, in which he sank four additional ships.

With nineteen ships sunk and four others damaged, Oesten is certainly among the Kriegsmarine’s aces of the deep. Following the war, he continued his passion for the sea. “In 1947 [I] started from the bottom again, and it wasn’t until 1956 that I had my first own company for ships of all types and sizes at shipyards all over the world. This work was important to me and I did it until I was 70.”

Others, however, spoke of the limited financial options that ultimately compelled their inevitable military service.

Transcribed through his daughter, Hans Günther Lange wrote, “The majority of German soldiers had nothing to do with Hitler and his blood company…[I] never joined the NS-Party. [I] hated (and despised) it. Nevertheless [I] started a military career. [I] had no choice because [my] father, a banker with many Jewish friends, lost his job and his money thanks to Hitler…and universities were very expensive in those days…”

Joining the Kriesgmarine in 1937, Lange initially served onboard a torpedo boat and later as a watch officer onboard U-431 in the Mediterranean Sea. In 1942, he assumed command of U-711 and subsequently led attacks against British and Soviet convoys throughout the Arctic Ocean. In the course of his twelve patrols – totaling 304 days at sea – Lange sank two ships and damaged one other. Lange also made a determined effort to sink a Soviet battleship and a neighboring Soviet destroyer; however his salvo of torpedoes detonated prematurely.

Most intriguing of U-711’s service were its espionage-like missions in the Arctic Ocean to monitor Soviet communications as well as strike remote Soviet radio and weather installations. In one instance, a small team of sailors and naval intelligence specialists onboard U-711 were placed ashore to reconnoiterer a remote Russian island in the far eastern waters of the Kara Sea. Other than perhaps prisoners of war, no other German combatants had ever set foot so deep in Soviet territory.

On May 4, 1945, while moored to a German depot ship at a U-boat anchorage in Norway, over three-dozen British Royal Navy aircraft attacked and sunk U-711, killing forty of Lange’s fifty-two-person crew. With eerie parallels to the ending of the 1981 war film Das Boot, this attack (known as Operation Judgment) was the last air raid in the European Theater of Operations during World War II.

One of the more pointed questions I sought to ascertain was how they, and their fellow U-boat sailors, ought to be remembered for their military service. Most lamented of a tarnished legacy.

“The German soldier was exposed to unimaginable mockery and demonization after the war” recalled Alfred Eick. “How fairly the German soldier heals is [determined] by the former opponent.”

Eick began his naval career in 1937 and served onboard a destroyer before transferring to the U-boat force in 1940. Between May 1943 and May 1945, Eick led U-510 on four patrols spanning 354 days at sea. During this time, his crew sank ten ships – including two American steam merchants and a tanker – while also damaging one other.

Eick, like Oesten, was one of only six Monsun Gruppe captains who survived the round-trip voyage from Europe and made port visits in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and even Japan. During Eick’s 103 day return voyage from Southeast Asia, U-510 ran out of fuel in the North Atlantic (despite refueling assistance from Oesten’s U-861 off the coast of Madagascar). Nonetheless, U-510 miraculously reached France on April 23, 1945.

For such a unique war record, Eick wrote of the struggle he and his fellow Kriegsmarine sailors faced at sea. “The cruelty of the war was particularly felt by the German submarine force. They had to defend themselves against an overwhelmingly superior force [and] fought chivalrously a hopeless fight. Out of 39,000 submarine [sailors], 28,728 were killed.”

“The German soldier did his duty like the soldiers of all other countries,” added Eick. “We, old soldiers, bow in awe of our dead comrades who have given their best, their young lives, in good faith for their country. [They] are the heroes of the German submarine force.”

Some were more blunt with their feelings of association to the Third Reich.

“For more than 60 years, all Germans – whether they are still alive or dead – have been held responsible for crimes by national socialists,” wrote Hans-Georg Hess. “I keep pointing out this discrepancy and defamation. Anyone who remembers soldiers in Germany will be viewed with suspicion and possibly punished for ‘sedition.’”

Joining the Kriegsmarine in 1940 at the age of sixteen, Hess served onboard minesweeping vessels before transferring to the U-boat force. In September 1944, Hess assumed command of U-995 and become one of the youngest U-boat captains of the war at the age of twenty-one. Hess subsequently completed five patrols (totaling 113 days at sea) throughout the Arctic Ocean and sank five Soviet ships and an American steam merchant. In addition to mine laying efforts in the Barents Sea, Hess – much like Lange’s U-711 – dispatched a small landing party from U-995 to reconnoiter a remote island off Russia’s Kola Peninsula.

Today, U-995 is one of only four surviving U-boats that have since been converted into museum ships. It is located near the German city of Kiel and receives nearly 350,000 annual visitors.

Like Hess, Hanns-Ferdinand Maßmann wrote, “Germany is still held under the jurisdiction of an ‘enemy state.’ None of [the American] or British politicians ever felt any obligation to end this second class humiliation of my country. Don’t ask me why even our politicians never objected.”

Joining the Kriegsmarine in 1936, Maßmann served as captain of U-137 in which he led an exceptionally short series of patrols during the summer of 1941. In one instance, after encountering no enemy traffic at sea after two weeks, he simply returned to port. Maßmann’s luck improved with his command of U-409 in which he sank five ships and damaged one other throughout the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. However, on July 12, 1943, Maßmann’s U-409 was sunk by depth charges from a British Royal Navy destroyer off the coast of Algeria. Maßmann was one of thirty-seven survivors from his forty-eight-person crew.

For others, the war was simply another event in their long life and one to which they did not hold impassioned beliefs. Perhaps they were simply thankful to have survived.

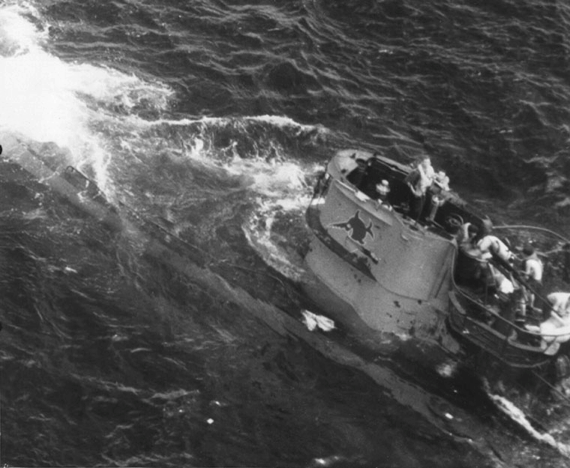

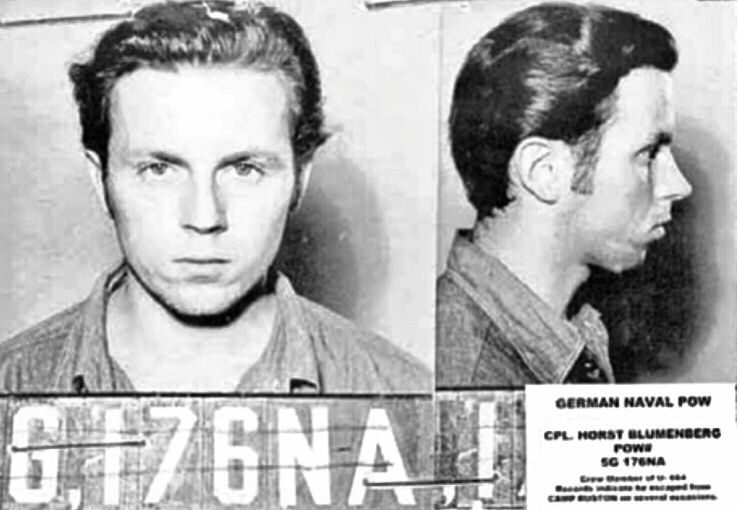

On August 8, 1943, in the North Atlantic, U-664 fired three torpedoes at the USS Card, an American escort carrier, but did not score any hits. The next day, aircraft dispatched from the USS Card subsequently sank U-664. This dramatic attack of bombings and strafing runs was captured on camera by the American aviators overhead. Onboard the sinking U-664, twenty year old Horst Blumenberg, an enlisted engineer, managed to escape to the surface. Turning to a photo, Blumenberg noted, “[t]he two men on the conning tower are the last ones leaving the sinking sub. I am the smaller one in the front.”

Afloat for nearly seven hours, Blumenberg and the reminder of his crew were rescued by the USS Borie before being sent to prisoner of war camps in the United States. Between 1944-1946, Blumenberg was interned at Camp Ruston in northern Louisiana where he escaped on four separate occasions. In one instance – while posing as lost Swedish sailors heading to the West Coast – Blumenberg and three others managed to flee nearly seventy-five miles before being apprehended by a Texas police officer. When questioned, Blumenberg and his fellow escapees complained of Camp Ruston’s frequent SPAM meals. The police officer bought them hamburgers and Coca-Cola drinks before handing them over to the FBI.

Following the war, Blumenberg settled in Kentucky. Despite such wartime adventures, he did not write a book or pen any memoirs. “That is what I should have done,” he remarked. When asked about the legacy of his Kriegsmarine years, he simply shared, “I do not want memories to my military service, because it is meaningless.”

To their credit, some were quite active in their later years in attempt to help educate future generations from their own wartime experiences.

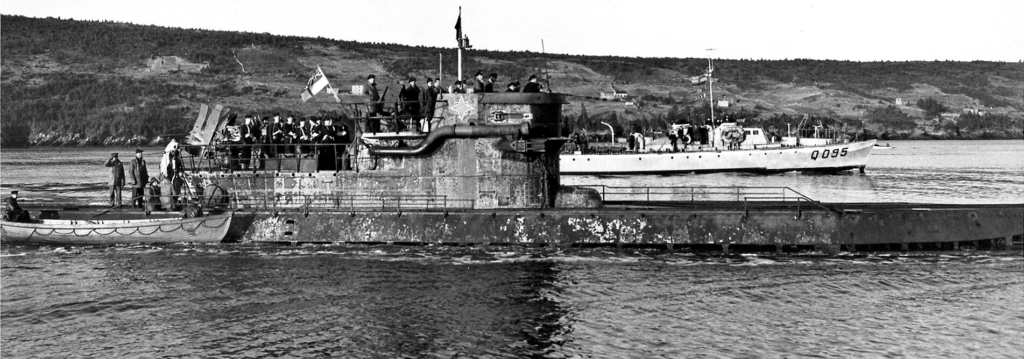

On April 16, 1945, U-190 sank a fleet minesweeper of the Royal Canadian Navy off the shores of Halifax. Less than a month later, the crew of U-190 surrendered and were escorted by the Royal Canadian Navy initially to Newfoundland and later – rather coincidentally – to Halifax. Werner Hirschmann, U-190’s chief engineer, would not only become a prisoner of war in Canada but would later become a resident in the land of his former warring opponent.

“I know a number of Canadian naval veterans who were involved in our encounters and attempts to kill each other and today we are best of friends,” Hirschmann wrote. “Is there any better indication of the absurdity of war? I am telling that story to the kids in high schools and their reactions, as I have in writing is, ‘Please come back and tell us more. We were never told any of this before.’ That is an award I cherish and I hope when they grow up they will remember me and what I have to say.”

In reference to his military service, Hirschmann explained, “I never felt I was fighting a war…but [was] simply a member of my chosen profession, living and coping at a time when there happened to be war…Our daily mood or activities were totally immune to whether we were winning or losing the war. Everything else was more important. We drank, had affairs, cursed our government (as any population does) had parties, worked, when necessary, 24 hours around the clock, laughed or cried as much as we could at any other time in our lives. We knew in 1944 that there was no chance that Germany could win the war. Did that knowledge affect our well-being or behavior in any way? Not a bit. We were expected to do our job and we did it until we were fired. At the end of the war he had a certain feeling of happiness for the fact that we were still alive which provided us with some degree of satisfaction for a job well done.”

Irrespective of their circumstances during the war – or the beliefs shaped after the war – these old wolves have all have passed away since I corresponded with them. Therefore, if you catch a glimpse of the fading World War II generation this V-E Day, be sure to grab their stories while they are still here.

About The Author: Kyle Nappi is an Associate at Booz Allen Hamilton, a Fortune 500 management-consulting firm in the Washington, D.C. metro area. This article was prepared by the author in his personal capacity. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, opinion, or position of their employer.

Mr. Nappi is also a recipient of the Naval Historical Foundation’s Volunteer of the Year award for efforts to return photographs and memorabilia seized on the island of Saipan to families of fallen World War II Japanese combatants.

Sources and Image Credits

- Blumenberg, Horst. “U-664.” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, April 12, 2007.

- Blumenberg, Horst. “Your Letter 12/5.” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, December 25, 2009.

- Deutsches U-Boot-Museum. “U 511 and the voyages of German and Japanese U-boats between Europe and the Far East.” The Voyage to the Far East. Accessed April 2020. dubm.de/en/the-voyage-to-the-far-east/

- Eick, Alfred. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Bielefeld, Germany, August 19, 2008.

- For Posterity’s Sake – A Royal Canadian Navy Historical Project. “HMCS U-190, Former German U-Boat U 190.” Accessed April 2020. www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_U-190.htm

- Frentzos, Christos. Thompson, Antonio. The Routledge Handbook of American Military and Diplomatic History: 1865 to the Present. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

- Geerken, Horst. Hitler’s Asian Adventure. Norderstedt: Books On Demand. 2015

- Harris, Wesley. “Bringing Back The Past.” The Minute Magazine, Volume 10, Issue 1, February 2015.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “Alfred Eick.” The Men – U-boat Commanders. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/men/eick.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “Hanns-Ferdinand Massmann.” The Men – U-boat Commanders. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/men/commanders/791.html

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “Hans-Georg Hess.” The Men – U-boat Commanders. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/men/hess.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “Hans-Günther Lange.” The Men – U-boat Commanders. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/men/lange.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “Jürgen Oesten.” The Men – U-boat Commanders. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/men/oesten.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-61.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u61.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-106.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u106.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-190.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u190.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-410.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u409.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-510.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u510.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-664.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u664.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-771.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u771.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-861.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u861.htm

- Helgason, Guðmundur. “U-995.” List of all U-boats. uboat.net. Accessed April 2020. uboat.net/boats/u995.htm

- Hess, Hans-Georg. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Idensen, Germany, June 14, 2007.

- Hirschmann, Werner. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Toronto, Canada, Septemer 12, 2009.

- Historica Canada. “Veteran Stories: Werner Max Hirschmann.” The Memory Project. Accessed April 2020. www.thememoryproject.com/stories/1434:werner-max-hirschmann/

- Lange, Hans-Günther and Barbara Mienkus. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Kiel, Germany, March 10, 2007.

- Manson, Jerry. “U-664A.” Individual U-boats. Accessed April 2020. www.uboatarchive.net/U-664A/U-664.htm

- Maßmann, Hanns-Ferdinand. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Bremen, Germany, March 23, 2009.

- McCormick, Harald. “After Forty Years: I Find Out How My Ship Was Sunk in World War II – and Meet the Extraordinary Man Who Sank Her!” Sea History. National Maritime Historical Society, No. 35, Spring 1985.

- Miederer, Max. “U510.”Das Bullauge – Österreichischer Marineverband. June/July/August 2014. Accessed April 2020. www.marineverband.at/regional/mk_salzburg/bullauge/bullauge_06-07-2014.pdf

- National Archives and Records Administration. Records Relating to U-Boat Warfare, 1939-1945. Guide to the Microfilmed Records of the German Navy, 1850-1945: No. 2. 1985.

- National Museum of the U.S. Navy, Naval History and Heritage Command. “Sinking of U-664.” WWII: 1943: Attacks on German Ships and U-boats. Accesses April 2020. www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/wwii/wwii-atlantic/battle-of-the-atlantic/engagements-german-uboats/1943-attacks-german/1943-aug-9-u-664.html

- Oesten, Jürgen. Letter to Kyle Nappi, Hamburg, Germany, March 29, 2010.

- Oesten, Jürgen. “Erinnerung.” E-mail message to Kyle Nappi, June 13, 2007.

- Paterson, Lawrence. Hitler’s Grey Wolves: U-Boats in the Indian Ocean. London: Greenhill Books, 2004.

- Royal Navy Research Archive. “A History of the 853 Naval Air Squadron.” Royal Navy Air Squadrons. Accessed April 2020. www.royalnavyresearcharchive.org.uk/SQUADRONS/853_Squadron.htm

- Smith, Peter. HMS Royal Sovereign and Her Sister Ships: Battleships at War. Pen & Sword Books. 2009.

- Uboataces.“Fate of the Far Eastern Boats.” U-Boats in the Far East. Accessed April 2020. www.uboataces.com/articles-fareast-boats6.shtml

- World War II Pictures In Details.“U-861 at Trondheim Submarine Base.” Accessed April 2020. ww2images.blogspot.com/2014/01/u-861-at-trondheim-submarine-base.html

- Zabecki, David. World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia (Military History of the United States). Routledge. 1998.

Naval History News and Anniversaries:

www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-045.html

www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-045.html

usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2015/04/24/john-paul-jones-comes-home-to-the-u-s-naval-academy/

Jeffrey

Pingback: Divine Wind: Reflections from Two Kamikaze Veterans | Naval Historical Foundation

Sabine Schleese

Brian Murza