By Captain Lawrence B. Brennan, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

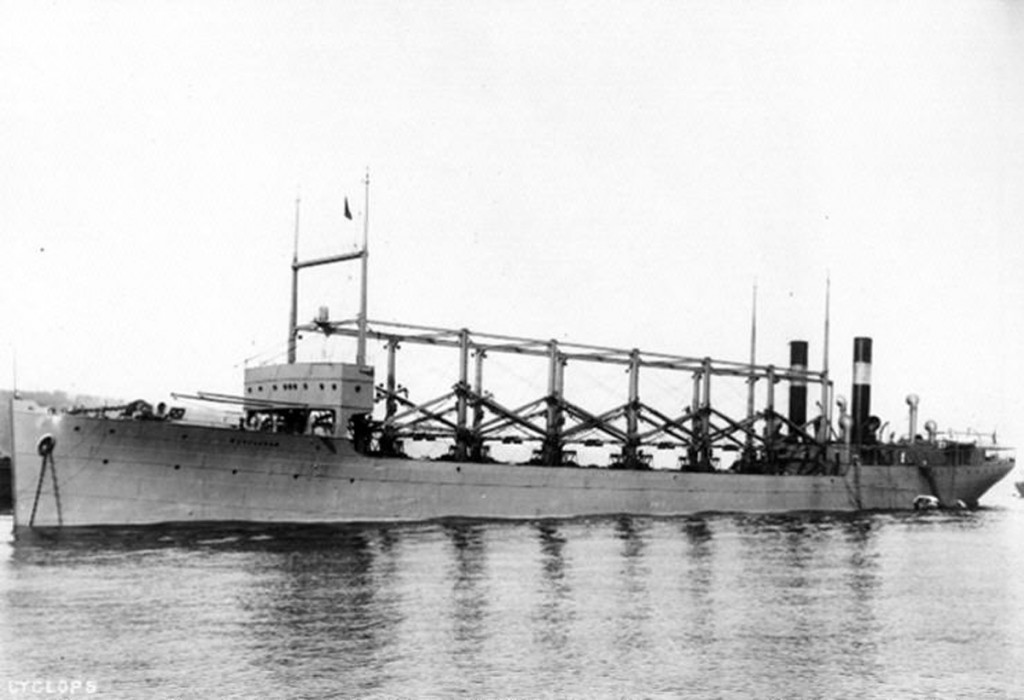

USS Cyclops photographed by the New York Navy Yard, probably while anchored in the Hudson River, NY, on 3 October 1911. National Archives photo 19-N-13451.

I. Introduction

Ninety-five years after the loss of USS Cyclops and 309 souls [1. www.history.navy.mil/danfs/c/cyclops-1.htm ] in the North Atlantic in March 1918, the precise mechanism of the sinking and the location of the wreck remain unknown. This incident, during World War I, is the largest loss of life in the history of the United States Navy of a U.S. built steel hulled warship where there simply is no direct evidence of why it happened, when it happened, or exactly how it happened. As we near the centennial of the loss of Cyclops, it is appropriate to remember the ship, her officers, and crew and to review their valuable contributions. Moreover, the long-accepted opinions as to the contributing causes of the loss of Cyclops may be helpful to the understanding of risks faced by commercial bulk carriers which have been lost at “an alarming rate” for many years.

In April 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany and other Central Powers, the U.S. Navy was in transition from coal burning warships to ships powered by oil. This would have a direct impact on the capital ships sent to the United Kingdom to reinforce the Royal Navy’s battleships. Ultimately, naval oil reserves would present major issues throughout the 1920s – the Teapot Dome Scandal concerned illegal leases of naval oil reserves, and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the colonial establishments in the Middle East were greatly influenced by the European navies’ demand for oil for their merchant ships and warships.

Following the Spanish-American War (1898) and the circumnavigation of the Great White Fleet (1907-09), the fleet’s worldwide demand for coal was viewed as a major weakness in its combat capacity. Dependence on foreign coal and foreign ships to transport that coal were major concerns. During the first fifteen years of the twentieth century, the U.S. Navy commissioned a dozen colliers. Some were converted to other types. [2. www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/usnshtp/ac/w1ac-2.htm%5D Two of these colliers would earn eternal mention – USS Jupiter would be converted to USS Langley (CV 1), the first U.S. aircraft carrier, and USS Cyclops would be lost in a mysterious manner that raised the concern and interest of the Navy, the nation, mariners, and historians worldwide.

II. Overview of Loss – The Last Voyage

Cyclops, the only ship of her class, was engaged in the transportation of bulk cargo to and from the United States to Brazil in early 1918. On 9 January 1918, she was assigned to Naval Overseas Transportation Service, departing Norfolk the day before with 9,960 tons of coal for English ships in the South Atlantic. [3. www.history.navy.mil/danfs/c/cyclops.htm 1.htm and Momsen, Richard O., American Vice-Consul in Charge, letter dated Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, April 27, 1918 concerning the U.S.S. “CYCLOPS” on which Consul-General Gottschalk was a Passenger.] She arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 28 January 1918; she departed Rio de Janeiro on 15 February, carrying a load of 10,800 long tons (11,000 t) of manganese ore, and on 20 February, Cyclops entered Bahia. [4. Momsen, Richard O., American Vice-Consul in Charge, letter dated Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, April 27, 1918 concerning the U.S.S. “CYCLOPS” on which Consul-General Gottschalk was a Passenger.] Two days later, on 22 February 1918, she departed for Baltimore, Maryland, with no stops scheduled. Rather than proceeding directly to Baltimore, as scheduled, Cyclops deviated to Barbados, arriving on 3 March 1918. At this port she was about 1,800 nautical miles from destination.

Before leaving Rio, Commander Worley, the commanding officer, reported that Cyclops’s starboard engine was inoperative because it had a cracked cylinder reducing her speed to 10 knots. This was confirmed by a survey board, which recommended that the ship return to the U.S. for repairs. There were suggestions that the ship was overloaded when she departed Brazil. Certainly, the addition of more coal in her bunkers and water at Barbados may have offset any reduction in draft achieved during the voyage north. Post-sinking investigations in Rio concluded that the ship had been heavily loaded. She had no prior experience carrying ore.

Cyclops departed Barbados for Baltimore on 4 March but never was seen again. A rumored sighting on 9 March off Virginia by the molasses tanker Amolco was denied by that ship’s master. It was improbable that Cyclops was off Virginia on that date because she was not due at Baltimore until 13 March, and her speed of advance was reduced to about 240 nautical miles per day because of the unseaworthy engine. The weather off the Virginia Capes on the following day, 10 March 1918, reportedly was violent. In any event, Cyclops failed to arrive at Baltimore and no wreckage has ever been found.

Absent direct proof it appears most likely that a synergy of events caused the loss of Cyclops. The ship was operating on a single shaft because of the cracked cylinder. This reduced her speed and maneuverability and left Cyclops at risk of greater damage if she were to suffer a further engineering casualty. She was loaded deeply, at or beyond her marks. This cargo was new to the ship and it is not clear that the officers, crew, and stevedores in Brazil knew how to properly load, stow, and trim the ore. There have been reports that she previously suffered hull damage due to a coal fire, hull failures, or separation of pipes, or hull and strength members. She also had problems with extreme rolls. On at least one occasion it was reported that her cargo had shifted. Water entering the hull would affect the ship’s stability and buoyancy, probably resulting in free surface effect that caused progressive flooding, and ultimately causing her to sink. This process may have been unperceivable to the bridge watch, particularly if it occurred during dark or extreme weather; they would have little notice that the ship was about to sink. If Cyclops had not previously lost her remaining engine, she may have continued to steam along driving the bow underwater, alternatively she capsized.

III. A Brief Introduction To Navophilately – The Postal History of Cyclops and The Legend of the Ship’s Postmark

A. The legend within the legend of Cyclops

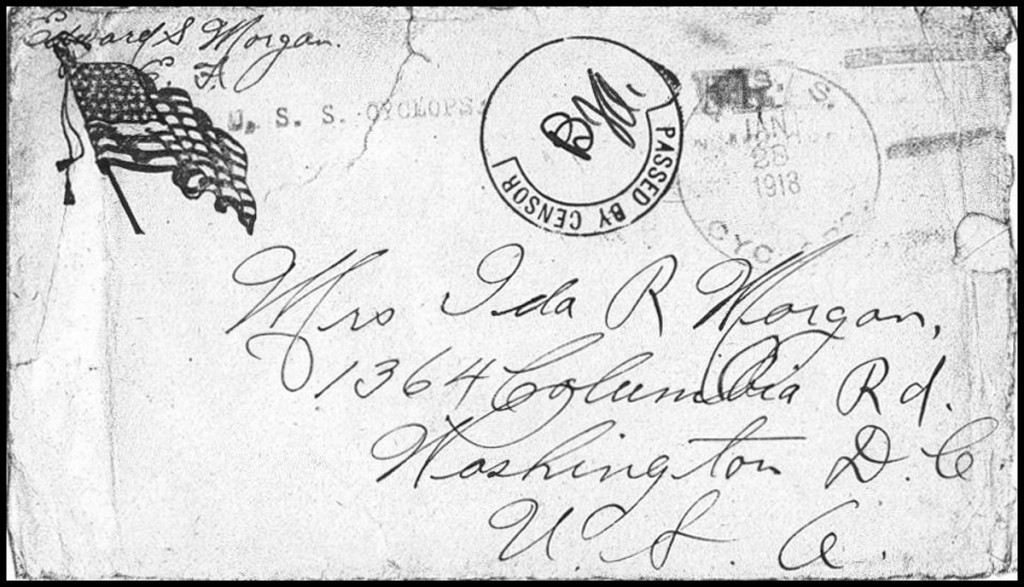

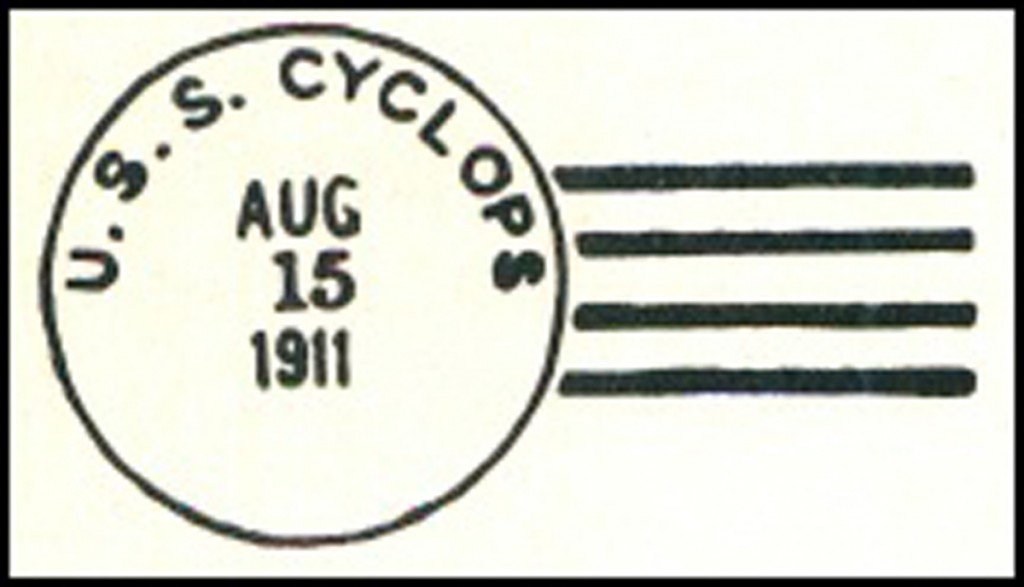

The history of USS Cyclops also involved the most interesting and contentious claim about a ship’s post office. Thanks to the untiring effort of Captain Todd Creekman, USN (Ret), Executive Director of the Naval Historical Foundation, and Marvin W. Barrash, the author of the definitive study of the ship titled simply USS Cyclops, [5. Barrash, Marvin W., U.S.S. Cyclops, Heritage Press: 2010.] a single genuine example of an envelope postmarked on board Cyclops has been located at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, where it has been for over 70 years. More than 90 years after the loss of the ship, naval postmark and cover collectors have been introduced to this unique cover. Cyclops had a post office on board for about seven months, from mid-July1917, when she returned from France, until her sinking. During that time she made a brief voyage to Nova Scotia and undertook her fatal cruise to Brazil. It is likely that Cyclops was carrying the fleet mail from Brazil to the United States when she disappeared. But the single, surviving cover with her postmark was dated 28 January 1918, the day of her arrival at Rio. Even if Cyclops was carrying the fleet’s mail when she departed nearly three weeks later, on 16 February 1918, it is probable that mail was carried by a ship that departed Rio at an earlier date in late January or early February 1918.

Following the April 1917 declaration of War by the U.S. Congress, Cyclops was commissioned on 1 May 1917, Lieutenant Commander G. W. Worley in command. She joined a convoy for St. Nazaire, France, in June 1917, returning to the east coast in July. Except for a voyage to Halifax, Nova Scotia, she served along the east coast until 8 January 1918 when she departed for Brazil with coal.

To a small group of collectors of naval postmarks, there has been a similar, but less morbid, mystery arising out of the loss of Cyclops. The first reported postmark from Cyclops, dated in 1914, was identified to collectors in the mid-1930s by a leading illustrator and student of naval postmarks. A copy of that postmark never has been published. In 1939, however, the same man help publish a Handbook of Naval Postmarks containing his illustration of a 1911 Cyclops postmark. For 60 years that postmark was advertised to be the rarest naval postmark, the only known example of a cancellation from Cyclops. By 1997, however, it was revealed that the 1911 Cyclops postmark was a fake. Unknown to collectors and naval historians, one legitimate example of Cyclops’s actual postmark has been in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library since 1942. Thanks to the diligence and scholarship of Captain Creekman and Mr. Barrash, collectors now are able to appreciate that postmark.

B. The only reported examples of Cyclops’s postmark and censor mark. [6. www.navalcovermuseum.org/restored/CYCLOPS_AC_4.html%5D

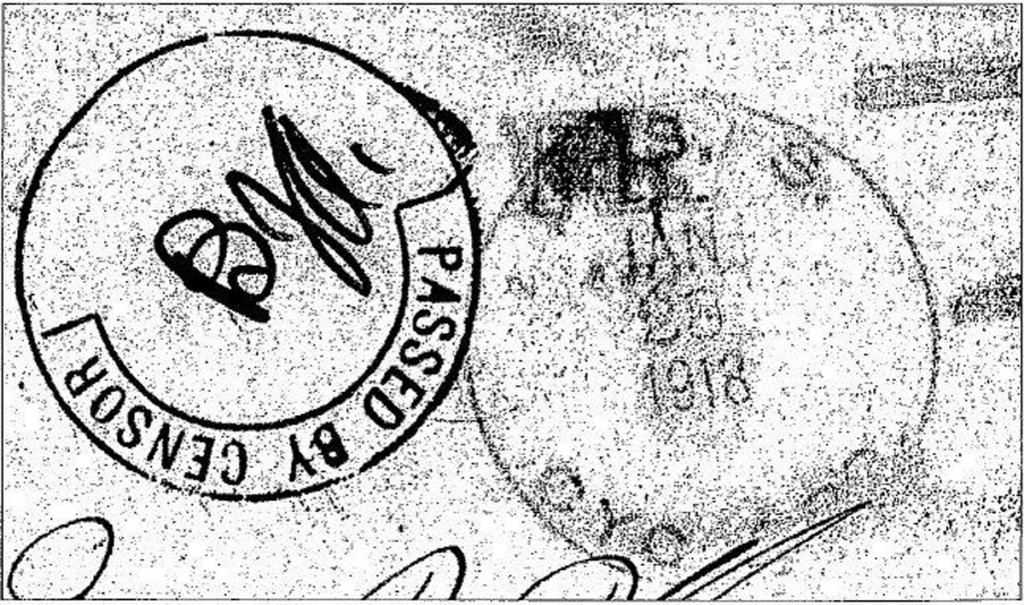

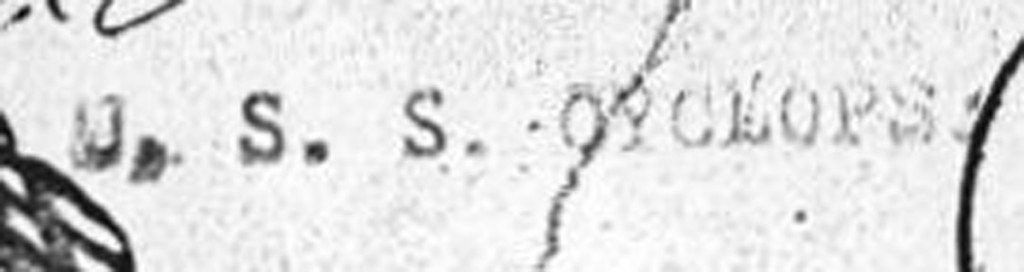

The postmark actually used on board USS Cyclops contained a circular dating device with the ship’s name and three killer bars. This has been labeled a Locy Type 3 cancel. It was somewhat unusual to issue a postmark with the ship’s name in the device during World War I. Rather, the norm was for the postmark to merely contain the words “U.S. Navy” in addition to the month, date, and year in the circular portion of the cancellation. Rubber hand stamp Type 3 cancels were issued beginning in 1913. [7. USCS Postmark Catalog, 5th ed. 1997 p. C 32 and content.yudu.com/Library/A1eeyk/ACatalogueofNonstand/resources/60.htm%5D

The censor’s mark is a style commonly used during World War I and the initials within the marking have been identified as Cyclops’s Assistant Surgeon Burt J. Asper, who also was lost with the ship. The reported similar Navy circular censor devices, with the words “Passed by Censor” at the top of a partial double circle, all contained dates for the censor and some contained the name of the ship within the device. During World War I, Navy censor devices were not standardized contrary to the Army practice and the censor marks of World War II. Many Navy World War I censor marks are unique, like the marking found on the 28 January 1918 Cyclops cover. [8. Kimes, Curtis R., Pictorial of World War One United States Fleet Hand Stamped Censor Markings (2d ed. 2010).]

C. Straight line rubber stamp- return address for “U.S.S. Cyclops” [9. www.navalcovermuseum.org/restored/CYCLOPS_AC_.html 4]

The third rubber stamp marking on the face of the cover is a single line with the ship’s name placed in the upper left cover, effectively forming part of the return address on this printed envelope provided to Sailors by the YMCA.

D. Collectors of ships’ mail.

For more than 80 years there have been organized collectors of postmarks and markings from U.S. warships. Those who have served as a Public Affairs Officer (or Public Information Officer) or as a Navy Postal Clerk undoubtedly encountered requests from collectors. They are not “spies” or “agents of foreign governments” but students of naval postmarks and covers (envelopes). The membership is worldwide and has included disabled veterans, flag officers, career sailors, new recruits on active duty, retirees, Pearl Harbor survivors, commanding officers, Coast Guardsmen, Marines, Chaplains, postal clerks (Navy Mail Clerks), retirees, civilians, women, children, even incarcerated prisoners, and Air Force veterans. We are a worldwide, eclectic group of collectors who carry on a hobby that began before most of us were born.

If you have served in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps you have enjoyed the benefits of the Navy’s Fleet Post Offices.

Naval post offices have been in existence since the cruise of the Great White Fleet, 1907-09, when they were authorized by Congress (Act of May 27, 1908). The Navy Department implemented the Congressional Act with General Order#14, dated June 17, 1908 and the first post office was established aboard the battleship, USS ILLINOIS (BB-7) July 8, 1908. Naval post offices were branches of the New York Post Office, and mail clerks were approved by the Navy Department, but appointed by the Post Office Department. [10. Master Chief John P. Young, USCGR (Ret.), Navophilately Before the USCS, 1930-32 online at www.uscs.org/resources/articles/navophilately-before-the-uscs-1930-32.%5D

In many respects, the Navy’s postal system functions remarkably like it did when it was established more than a century ago. It transports mail efficiently and inexpensively (at least for the senders) to and from ships around the world. The primary purpose of the postal system is to transmit official and personal mail to and from the deployed fleet. A Sailor or Marine can send mail at the prevailing US domestic rate no matter where stationed. And in time of war or other hostilities, “Free Mail” often is authorized for service members in specified areas.

In the early twentieth century Sailors were part of a world-wide post card craze. Like email of a later era, postcards were brief and inexpensive ways to communicate. While they were not instantaneous, post cards often carried photographs or illustrations of distant and exotic places; destinations that many could only dream about. Sailors and Marines, of course, had unsurpassed opportunities to visit ports around the world. The recruiting slogan, “Join the Navy and See the World” was truthful advertising. The cruise of the Great White Fleet was a seminal event in the operational reach and scope of the U.S. Navy.

During the round-the-world cruise, sailors sent penny postcards from foreign ports which were posted aboard the ships. Letters to family and friends were saved, along with the envelopes that bore the ship’s cancellations. The actual collecting of naval postmarks probably began after the return of the battleships from the cruise. [11. Master Chief John P. Young, USCGR (Ret.), Navophilately Before the USCS, 1930-32 online at www.uscs.org/resources/articles/navophilately-before-the-uscs-1930-32.%5D

Sparked by Air Mail service and the opening of new flight routes, during the 1920s stamp collectors became interested in collecting postmarks on envelopes (covers). [The term “cover” is particularly confusing in the naval service; ordinarily we understand a “cover” is what a civilian would call a “hat”. To a philatelist a “cover” is what a non-collector would call an “envelope”.] Naval cover collecting was an outgrowth of this 1920s hobby. During the 1930s, collectors would join together and form the Universal Ship Cancellation Society, now in its ninth decade. [12. www.uscs.org or on Facebook online at www.facebook.com/#!/groups/uscsnavalcovers/?fref=ts ] [Again, the word, “Cancellation”, in the Society’s title, may cause confusion to most readers. In this context, “cancellation” means “postmark” not the termination of a shipbuilding project or decommissioning of a ship.] Collectors are not opposed to shipbuilding. To the contrary, they tend to be strong proponents of new ships and since the early 1930s have celebrated shipbuilding events (keel laying, launching or christening, and commissioning) with cacheted commemorative envelopes. [A cachet is a printed or rubber stamp marking placed usually on the left face of the cover noting the ship and event. Many ships have their own rubber stamp cachets to add to collectors’ envelopes.] The Society and collectors have continued through World War II and the current era when security and censorship concerns made it impossible to obtain postmarks and covers. They have thrived during the cruises of USS Constitution, the Two-Ocean shipbuilding programs of the late 1930s, the massive first nuclear ship construction programs from the late 1950s through the middle 1970s, the space recovery programs of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo during the 1960s and 1970s. Collectors have been students of different types and styles of postmarks and an elaborate system of classifying postmarks was created in the late 1920s by a Navy doctor, Lieutenant Commander Francis E. Locy, MC, USN, who was awarded the Navy Cross for service with the U.S. Marine Corps during World War I. [13. www.navalcovermuseum.org/restored/Locy_System.html%5D

Despite service of nearly a decade and crews ranging to 250 officers and men plus the demand of official correspondence, only a single example of Cyclops’s postmark has been reported. This is on an envelope sent by a crewmember when Cyclops was in port in Brazil. Cyclops was not in commission until World War I and her post office was not opened until mid-July 1917. The cover bears a censor’s marking initialed by the Assistant Surgeon Burt J. Asper. Surprisingly, the postmark contains the ship’s name “USS Cyclops” in the circular device, while most other postmarks issued during World War I (as well as World War II) merely read “U.S. Navy” [14. During World War I and World War II, Navy removed ships’ names from most postmarks and issued cancellation devices which generally read “U.S. Navy” in the circular device. Postmarks which do not contain the ship’s name but have “U.S. Navy” instead have been classified as “Z” postmarks; the most common are types 2z, 3z, both rubber hand stamp cancels, and 7z, a machine postmark.] . It has every indicia of actual use – as Sailor’s mail it would be difficult to question the provenance of this cover and cancellation. But for decades there was another “postmark” purportedly from Cyclops which now is acknowledged to be a fraud.

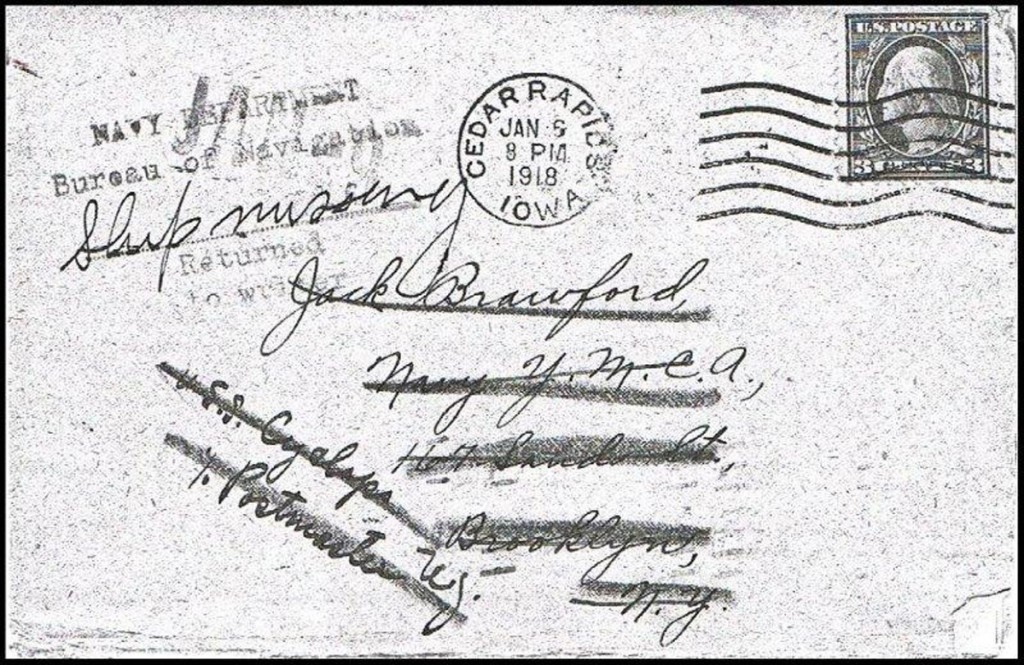

E. Face and reverse of envelope addressed to Cyclops crewmember lost with the ship. The envelope was returned to sender from the Bureau of Navigation on 17 May 1918 with the annotation “Ship missing, returned to writer” on the reverse and face. [15. www.navalcovermuseum.org/restored/CYCLOPS_AC_4.html%5D

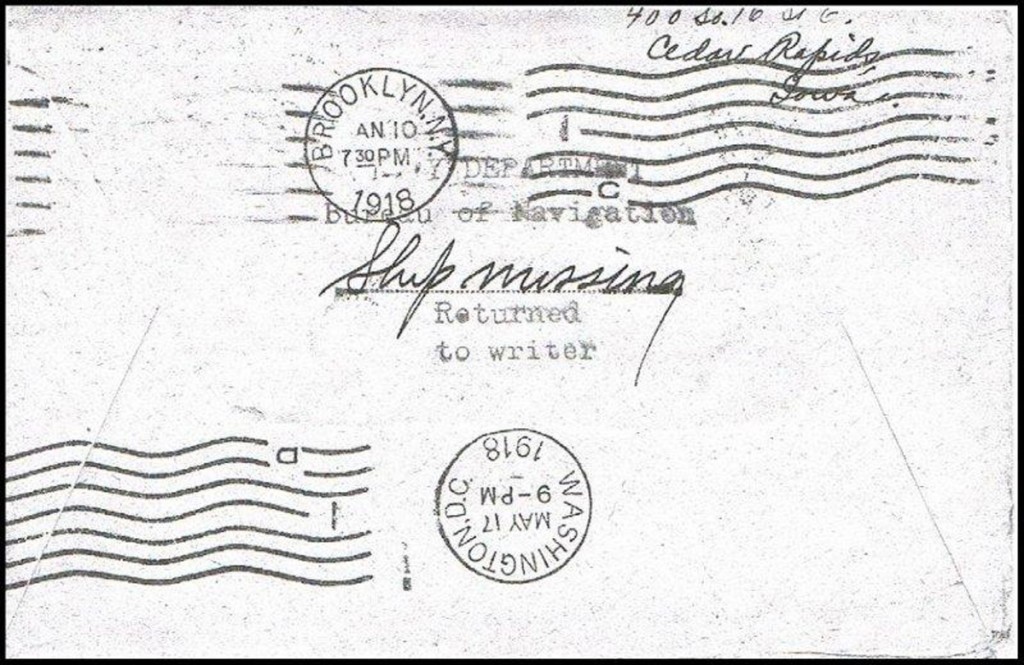

F. The fake Cyclops Type 1 postmark counterfeited by John E. Gill (USCS Honorary Member 39) during the 1930s. [16. www.navalcovermuseum.org/restored/CYCLOPS_AC_4.html%5D

For more than 60 years the only reported postmark from Cyclops was a rubber stamp hand cancel (Locy Type 1, containing a circular dating section with the ship’s name and four killer bars). That postmark has been discovered to be “a fake” – the creation of an early collector and contributor to the original postmark handbooks. [17. USCS Postmark Catalog, 5th Ed. 1997, p. C 32.] A genuine postmark and cover from Cyclops, however, was located nearly 100 years after the ship first was placed in service.

In the 1930s an early student of naval postmarks, John Gill of Massachusetts, reported that he had found the first cover from Cyclops. Now it understood that this Cyclops postmark was a forgery or fraud. That full cover was never copied and accounts varied from merely a postmark on a full cover or a post card. The only published copies of the postmark do not appear to have been used on mail as there are neither postage stamps nor the word “Free” commonly written by Sailors in lieu of paying postage during hostilities. The history of Gill’s postmark from Cyclops has been illusive and self-contradictory. Importantly, the postmark initially was reported to be dated 1914 and subsequently the date was changed to 1911.

The 1939 Handbook of Naval Postmarks lists the cancel as a Type 1 postmark dated 1914: It was priced at $2.00, about the highest price of any postmark listed (Gill and Handbook publisher Joe Hale were close personal friends). No further information about the ship was listed. In the 1952 Catalogue, published in a Billig Philatelic Handbook, the cancel was listed again, but this time with a year date of 1911. This edition reported that the ship was commissioned on 7 November 1910, and her post office was established on 20 February 1911. A post office closing date of 1 March 1918 is given, presumably the date of the last month-end report the Postal Clerk had sent in while they were still in port in Barbados. The cancel was now listed with a value of $15.00, ten times the average value of other classic cancels. Gill provided a drawing of the cancel, the very first illustration in the discussion of cancel types. It eventually became featured in the explanation of the Locy Type Chart as the example of a basic Type 1 cancel (Figure 7). [18. Kent, David A., “Naval Cover Fakes, Forgeries and Frauds Part XIV”, USCS LOG, January 2011, p 70.]

More than 15 years ago, the Universal Ship Cancellation Society published a revised and expanded edition of the Postmark Catalog. Editor-in-Chief, David A. Kent, a USAF officer of the Vietnam era, wrote:

[R]umors that the CYCLOPS cancel was a fabrication were too strong to ignore, so we turned to official postal records for more information. … [W]e find no listing for CYCLOPS in the 1911 Postal Bulletins. She is also not listed in the Postal Guides during this period. We do, however, find a listing in a 1917 Postal Bulletin stating that a post office was authorized for CYCLOPS on 13 June 1917, shortly after she was commissioned. The only edition of the Postal Guide that lists her is the 1918 edition, ironically four months after she disappeared (the Navy did not officially list her as “lost” until that edition was already at the printers), …

I believe that, at first, Gill made the cancel purely as a lark, an interesting experiment to test his artistic skills. When someone pointed out that his 1914 year date seemed odd, since the standard cancel that year would have been a Type 3, not a Type 1, he changed the date to 1911, and then produced a drawing to prove it. It would also appear that the 1911 post office establishment date was pure fiction, to justify the cancel. Although many people have written about seeing the cover over the years, no full description of it has ever been published. It’s been more than 30 years since anyone has seen it, and those that did tend to have a vague recollection that the cancel seemed too sharp, and it might have been on a piece of postal stationery, just like the facsimile covers that Gill made. I believe that we must accept the truth that the famed CYCLOPS cover, too, was made by Gill himself from a metal printing plate on an old unused stamped envelope. [19. Kent, David A., “Naval Cover Fakes, Forgeries and Frauds Part XIV”, USCS LOG, January 2011, p 71. ]

Mr. Kent’s current account, however, is internally inconsistent. Query, why would Mr. Kent state that Gill made fabricated the postmark and then printed it from a steel plate on “an old unused stamped envelope” when, earlier in the same article, he contended:

nor has there been a detailed description of it — in fact, we aren’t sure whether it was a full cover or a picture postcard, which is where most early classic Navy cancels are found, The Gill family reports that they no longer have the cover, it having disappeared long ago under mysterious circumstances. [20. Kent, David A., “Naval Cover Fakes, Forgeries and Frauds Part XIV”, USCS LOG, January 2011, p 71. ]

In any event, the current edition of the Postmark Catalog boldly states that the Gill postmark from Cyclops was “a fake”. [21. USCS Postmark Catalog, 5th Ed. 1997, p. C 32.]

It is indisputable that there was mail sent to and from Cyclops and that a post office was established on board ship. There should have been a significant volume of mail for official business, primarily to the Bureaus at OpNav, and to and from family and friends. There are multiple factors why the envelopes with postmarks from the ship were not preserved. World War I was before collecting covers became a hobby. Family and friends were more interested in the contents of letters than the envelope. When the ship and crew were lost it many distraught survivors destroyed the correspondence as was the custom. Moreover, the ship had been in service for nearly seven years prior to the establishment of her post office. The officers and crew may have been in the habit of sending the mail from port rather than the on-board post office and perhaps they expected that mail posted ashore would be moved faster.

IV. Correspondence From One Cyclops Sailor To His Family

Following are extracts of correspondence from one young sailor who was a member of the crew of Cyclops from the summer of 1917 until she was lost. The letters, along with one envelope bearing Cyclops’s postmark and censor marking, are now located in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York having been donated in 1942 by Ewing S. Morgan, a relative of the Sailor, Edward S. Morgan, Jr. to President Roosevelt, a noted philatelist, who was Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the Wilson Administration. [22. Reproduced with the gracious consent of Marvin W. Barrash from U.S.S. Cyclops, Heritage Books, 2010.]

Fireman Third Class Edward S. Morgan, Jr. enlisted in the Navy soon after the declaration of war. He was at a training camp in Norfolk, Virginia on 10 August 1917 when he wrote to his mother reporting that he had enjoyed his first liberty the night before and that he was “a finished Sailor, … I am about to go aboard a Ship in about a week. When and where we are sent we never know so you see it will be pretty hard to keep in direct communications with home.” Two months later, on 10 October 1917 he wrote from Cyclops then at the New York Naval Ship Yard (Brooklyn Navy Yard). Six weeks later he still was on board Cyclops at Brooklyn celebrating Thanksgiving Day when he wrote to his sister, Mable. On 5 December 1917 Cyclops was at Baltimore, Maryland scheduled to depart early on the morning of 6 December 1917. One the last day of 1917 Fireman Third Class Morgan wrote from Cyclops at the Norfolk Navy Yard to his brother, Clarence. The envelope was posted ashore at Norfolk, most likely to avoid censorship since Edward freely discussed the intended voyage of Cyclops. The schedule he outlined differed greatly from Cyclops’s fatal voyage. The cruise was intended to last half a year starting with a voyage to the South Atlantic to deliver coal. Next, Cyclops was scheduled to sail to the Falkland Islands, a 28 day voyage. Thereafter, she was to pass through the Panama Canal and proceed to the Philippines. Edward expected to be promoted to Fireman Second Class and eventually become an Oiler. He wrote another letter mailed on board Cyclops on 28 January 1918 addressed to his mother. While the envelope has been preserved the letter was not among the papers presented to President Roosevelt. The final letter was written while Cyclops was in Brazil and arrived at the family home in mid-March 1918. Mr. Barrash writes that Fireman Morgan “told only of the part he was playing in the movements of the vessel.” [23. Reproduced with the gracious consent of Marvin W. Barrash from U.S.S. Cyclops, Heritage Books, 2010.]

V. Mail and letters from Cyclops

The following are Marvin Barrash’s extracts of letters from one member of the crew of Cyclops to his family in 1917 and 1918. The sole genuine example of a postmark from Cyclops was found among this correspondence. All are letters from 23 year old Fireman Third Class Edward Scott Morgan, Jr., of Washington, DC. who reported aboard Cyclops on 24 August 1917. The following letters were handwritten. Several portions have been omitted.

————————————————————————————-

[Letter was written from training camp prior to reporting aboard Cyclops.]

Norfolk, Va.

August 10, 1917;

Dear Mother,

As we did not have a drill period this afternoon I decided that I would write you just a word. I am located in the main camp now and we were given liberty for the first time last evening August the ninth and you can imagine how glad I was when they turned us loose.

I guess you will be surprised to hear that I am a finished Sailor, and that I am to go aboard a Ship in about a week. When and where we are sent we never know so you see it will be pretty hard to keep in direct communication with home. Mother read this carefully. Tell Clarence that if ever anything should happen that would require my returning home at any time it is absolutely necessary that he send me a telegraph. That is the only way I would be able to get a furlough and in any emergency do not fail to wire me immediately. I expect to be a wireless operator before long, but it will take a little hard work before I am able to qualify. Everything is progressing nicely, and the life is rather fascinating after a fellow gets used to it. We arose and had breakfast this morning at 4 a.m. so you can easily see they do not mind getting us out of our hammocks rather early, but as every man gets up at the same time we do not worry much about it. I have had several light spells of sickness since I have been here, but I am over them now … tough as leather, and as hearty as can be. I can do something I never did before, and that is roll up in any old hole, or on top of a table and go to sleep.

————————————————————————————-

[Letter was written while the U.S.S. Cyclops was at the New York Naval Shipyard, more commonly known as the Brooklyn Navy Yard.]

U.S.S. Cyclops,

October 10, 1917;

Dear Clarence,

As we are having the afternoon off; I thought that it would be a good opportunity to drop you a line. Clarence I am enjoying the sights, of our largest city now. I was on Broad Way several days ago and it certainly is a sight to see the bright lights at 45 St. I also traveled in the Subway which is a regular treat for one from Washington. Upon entering the East River we passed under the Brooklyn Bridge; out top masts were but about one foot from touching the bridge.

We are now in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and intend to stay here for an indefinite period. Some of our men are getting eight day furloughs, but as you have to draw for one, and as I am a very poor gambler I run a very poor chance of getting one. …

————————————————————————————-

[Letter was written at the YMCA, on YMCA stationery, while Cyclops was at the New York Naval Shipyard.]

U.S.S. Cyclops,

November 30, 1917;

Dear Sis Mable,

It is now 9:30 by the Y.M.C.A. clock; and as the rays of the beautiful Sun of this most Glorious Thanks giving Day streams into this room I will attempt to write you a few lines.

Tell Minnie that I received her letter at 11:30 Wednesday night, and I was surely glad to get it because I am invited to dinner at a private residence in the city, and if I had not received the letter I could not have gone. The jersey that Clarence sent me is just what I have been wanting. The muffler is certainly a fine one, and the head gear came in handy last Sunday night when we had to answer a fire call in the yards.

There were over 200 couples there, and I think I missed one dance during the evening, and I had fine young ladies all by myself at refreshment time. So you see you really have apopular Sailor Brother after all.

That is just one of the many dances I have attended in the last three weeks, There is a chance that I may be able to get home for a few hours in the next week or two. Please write soon, and tell me all about home.

————————————————————————————-

[Letter was written while Cyclops was at Baltimore, Maryland on Y.M.C.A. stationery]

U.S.S. Cyclops,

December 5, 1917,

Dear Mother & All,

I am now in Baltimore but I am sorry to state that I will not be able to get home this time. We leave here Dec. 6, at 7 a.m. so it will be impossible for me to come home. We are going South on this trip so it may be some time before you hear from me again.

If you send me a Xmas box be sure not to send anything that is perishable. I am feeling fine as always and I sincerely hope that you at home are feeling well also. …

Tell the girls not-to send me any clothes other than “socks” as I am overloaded now, but tell them they can send me a box of cakes & candies & Nabisco as all the fellows are receiving such a box; sent to them from home so I do not care to be the only one not to receive one.

————————————————————————————-

[Letter was written at the Y.M.C.A., Norfolk, Va. while Cyclops was at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Envelope postmarked 9-PM December 31, 1917, Norfolk, Va.; not a shipboard postmark.]U.S.S. Cyclops,

December 31, 1917;

Dear Brother Clarence,

On this the last day of the old year I sit here in the Y.M.C.A. thinking of home. Clarence we are preparing for a trip which will last about six months. We sail for the Falkland Islands in the near future; from there we visit the Philippines so you can judge how long it will take us to go and return. To go to the Falkland Islands it will take 28 days.

Do not worry about me as I am in the best of health and I expect to have the best time of my life.

I am working in the machine shop so I am having a soft time of it and further more I will be rated 2 Class Fireman on January 10, so I will then receive $41 per month. …

I have not had a slow moment since I have been in and the prospects for a slow time are small for the next six months; so I want you mother & all at home & live happy and forget your worries as I have done.

Boy at the rate I am going I will be an Oiler when I return home, and also as big as a house. Boy as soon as I joined the Navy I had no worries and I began to enjoy life. …

Give mother all my best wishes of the season and tell them that when the song birds and the roses bloom I will return home again. Ewing can tell you where the islands lie. We will go though the Panama Canal. There will be no U Boats to worry us so you need not worry about that part of it.

Edward S. Morgan, Jr.’s family last heard from him in a letter that he mailed while Cyclops was in Brazil. That letter arrived at his parent’s home in mid-March, 1918. “He told only of the part he was playing in the movements of the vessel.” [24. Barrash, Marvin W., U.S.S. Cyclops, Heritage Books, 2010.] Mrs. Ida R. Morgan, Edward S. Morgan, Jr.’s mother died, at the age of 54, on 19 September 1919. [25. Obituary, The Washington Post; September 20, 1919; page 2. Washington, D.C.]

An envelope, postmarked on Cyclops on 28 January 1918, without a letter, was among the collection of Morgan letters [26. The Edward S. Morgan, Jr. letters were sent to President Franklin D. Roosevelt by Ewing S. Morgan, Birmingham, Alabama in February, 1942.] addressed to the sailor’s mother. It bears significance as it was postmarked on board Cyclops at Brazil and was also stamped with a device, “Passed by Censor”. The Censor [27. Dr. Asper Was Lost on Boat”, The Star and Sentinel, p. 1, Gettysburg, PA., Saturday, April 20, 1918.] for the ship was Assistant Surgeon Burt. J. Asper, whose initials, “BJA” appear, handwritten within Censor’s marking.

Conclusion

The loss of Cyclops 95 years ago was the first major fatal loss of a steel hulled steam ship carrying bulk cargo. Furthermore, it is the largest loss of life in a single ship casualty involving a bulk carrier, albeit a warship. There were a number of ships carrying bulk cargo which were lost, including two ships in 1940 and two of Cyclops’s sister ships in the early years of World War II. More than 400 bulk carriers were lost from all causes in the 30 years between 1967 and 1996 with more than 10 ships lost each year between 1977 and 1996 except for two years; a total of 375 bulk ships were lost between 1977 and 1996, an average well over one ship per month for two decades.

The investigation and study of the loss of Cyclops should be undertaken to increase safety of life at sea. It is an appropriate learning experience not only to honor the memory of the officers and men lost with Cyclops but to attempt to determine the cause of this tragic loss of many Sailors and their ship 95 years ago.

Captain Lawrence B. Brennan, JAGC, U.S. Navy (Ret.) is an admiralty lawyer who has tried many major maritime casualty cases for the government and private parties. His emphasis is on collisions, strandings, fires, explosions, and environmental disasters, particularly oil spills.

————————————————————————————-

James W (Jim) DuVall

Robert Guthrie

Dennis J Psoras

Pragyan

Pingback: The Bermuda Triangle and Others | Book of Research

Pingback: USS Cyclops | amonghexagons

HEATHER SPRAGUE

Ed

Richard Bauer

Pingback: Bermuda Triangle Mystery - A Secret Revealed! | CSGlobe

bill bob

Pingback: Bermuda Triangle Mystery – A Secret Revealed! | Conspiracyclub

T.F.

T.F.

Pingback: 10 Baffling World War I Mysteries We May Never Solve | Give Me Liberty

Pragyan

Ed

Pingback: December 5, 1945 – Flight 19 Vanishes While on Routine Training Mission | This Week in History

Thomas

Pingback: Disappearance of the USS Cyclops | Thinking Sideways Podcast

Dave Wendes

Pingback: 5 Mysterious Ocean Places That Science Has Yet to Explain

Pingback: Bermuda Triangle Mystery Disappearances My Be Due To 'Hexagonal Clouds' - Use It DoUse It Do

Robert Guthrie

Fred willes

ken

realigned

Pingback: Bermuda Triangle thriller 'solved,' scientists say - Trending Hits

Pingback: 3 Mass Disapperances In American History – Creepyhistory.com

Pingback: Tea Leaves - DailyChatter

Pingback: 10 KISAH MISTERIUS & RAHASIA TENTANG SEGITIGA BERMUDA YANG BARU TERUNGKAP!! - Info Menarik Terbaru

Pingback: USS Cyclops Disappearance | Historic Mysteries

Sandra Johnson

Michael Mohl

Pingback: Redondo Beach man among those who disappeared aboard the USS Cyclops in 1918 – South Bay History

Thomas P Naughton