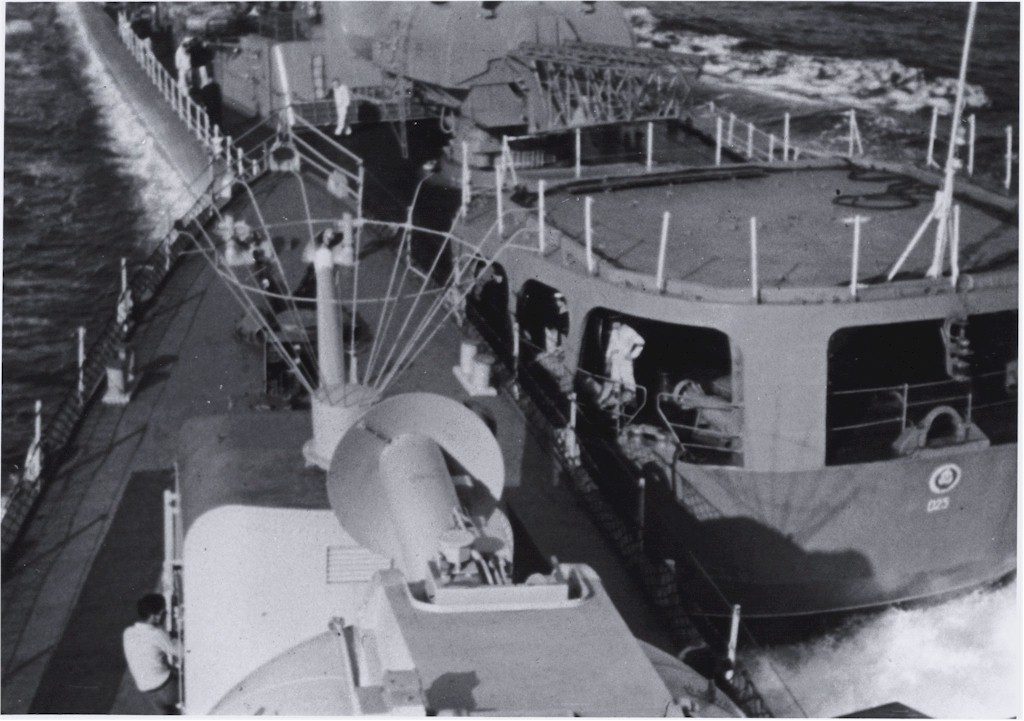

USS Gravely on June 17, 2016 from the deck of Russian frigate Yaroslav Mudry. (Image courtesy RT via USNI News); serving refueling operations between USS HORNET (CVS-12) and USS TALUGA (AO-62) in the Sea of Japan, 9 May 1967. USS WALKER (DD-517) is in right background. (NHHC Photo # USN 1123797)

On Friday June 17, the destroyer USS Gravely (DDG 107) passed in front of the Russian frigate Yaroslav Mudry (FF 727) in the Eastern Mediterranean. Video from the Russian frigate shown on Russian Television (RT) captured the aggressive maneuvering of the American missile destroyer which an RT newswire claimed “neglected Rule 13 [International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS)], which stipulates that an overtaking vessel must keep out of the way of the vessel being overtaken.” Missing from the footage was the nearby aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman (CVN 75) which Gravely was escorting. A U.S. official informed USNI News that the Russian frigate had been attempting to close in on the American aircraft carrier which was stationed in the region to conduct flight operations against ISIS. Six days later, it was reported that the same frigate approached within 150 yards of the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) while that carrier was conducting flight operations in the eastern Mediterranean. That the Gravely shouldered off the Russian frigate on the 17th was reminiscent of similar confrontations at sea a half century ago.

In the summer of 1966, the destroyer USS Walker had departed Vietnamese waters to participate in a joint U.S.-Japanese antisubmarine exercise in the Sea of Japan. On July 24, 1966, the Besslednyi (DD 022) a Soviet Navy Kotlin-class destroyer joined up with the allied task force and assumed a tailing role. Walker kept an eye on the Besslednyi, with orders to screen away the snooping Russian visitor should she try to charge towards the center of the allied ship formation. A Lt. (jg) on board the Walker later recalled that during this transit, the Soviet warship was not really persistent in her attempts to break into the formation. As with this most recent Gravely-Yaroslav Mudry encounter, American screening efforts were effective enough to draw a formal Soviet protest issued on August 10, 1966.

Ten months later, the Walker again entered these waters. As part of Task Group 70.4, Walker joined the destroyer USS Taylor and destroyer escort USS Davidson to provide a screen for the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. At 1030 on May 9, 1967, the Besslednyi reappeared to assume shadowing duties. Throughout the day, the Besslednyi turned into the screening Taylor on several occasions and backed off only when the American destroyer refused to yield. At one point, only 50 feet separated the two ships. As night fell, the Soviet ship retreated, keeping five miles away from the formation.

About 0845 the next morning, the C.O. of the Walker, Comdr. Stephan W. McClaren, received orders to relieve the Taylor of her shouldering duties. At approximately 0900, McClaren assumed the conn of the Walker and within fifteen minutes had his ship positioned between the Soviet and the Hornet. For the next two hours, Walker strove to keep the Russian destroyer at bay. One observer counted fourteen approaches during which the Besslednyi came within 100 yards. Four of these approaches were within fifty yards, and two came within fifty feet. At 1106, the two ships had maneuvered themselves into a collision situation. With the Soviet ship approximately thirty-five feet off Walker’s starboard beam and still closing, the Officer of the Deck, Lt. (jg) John C. Gawne, USN, dashed for the 1MC (the ship’s public address system) and passed the word: “Standby for collision starboard side, that is standby for collision starboard side.” He then sounded the collision alarm.

USS Walker (DD-517) colliding with the Soviet Kotlin class destroyer Besslednyi in the Sea of Japan, 10 May 1967. NPC #1166379. (Image Courtesy NAVSOURCE/DCC(SS/SW) David Johnston, USN)

In the early dawn of the following day, the Besslednyi departed, relieved by an older Krupnyy-class (DDGS 025) destroyer. Shortly after her arrival, the Krupnyy transmitted a flashing light message to the Hornet:

TO COMMANDER OF TASK FORCE, DURING 9TH AND 10TH OF MAY THE U.S. NAVAL SHIPS TAYLOR AND WALKER SYSTEMATICALLY AND ROUGHLY VIOLATED INTERNATIONAL RULES OF THE ROAD AT SEA AND MADE DANGEROUS MANEUVERING WHICH CAUSED DANGER OF COLLISION WITH SOVIET NAVAL SHIP. AS A RESULT OF SUCH A HOOLIGANS ACTION THE DESTROYER WALKER RAN DOWN THE PORT SIDE OF SOVIET DESTROYER 022 AND CAUSED DAMAGE TO HER. SUCH ACTIONS OF NAVAL SHIPS CANNOT BE AFFORDED. REQUEST STOP THE VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL RULES OF SHIPPING AT OPEN SEA IMMEDIATELY. COMMANDER SOVIET TASK FORCE.

At 1059 on May 11, the Walker received orders to resume shouldering duties. For the next three hours, the Krupnyy stayed approximately a mile off Walker’s starboard quarter, paralleling the American ship’s course and matching her speed. Relieved for an hour and a half to refuel, Walker again resumed her watchdog duties. At the request of Commander McClaren, Lt. (jg) Gawne had been the Officer of the Deck since 1030. Gawne recalled that in the late afternoon after the formation had reversed course, the Russian destroyer made several attempts to break past the Walker to approach the carrier. Each time the American destroyer blocked the Russian’s path. After one series of maneuvers, the Russian ship had positioned itself ahead of the Walker’s starboard bow. Suddenly, DDGS 025 came left, placing both ships in extremis. Gawne signaled, “YOU ARE STANDING INTO DANGER” and “DO NOT CROSS AHEAD OF ME.” The Lt. (jg) then sounded the danger signal–six short blasts on the whistle, and then passed the word over the 1MC “Standby for collision starboard side forward, standby for collision starboard side forward.”

After the two ships collided, the Krupnyy continued to the right and then stopped about 1,000 yards from the twice-hit American destroyer, which now sat dead in the water with her crew again scampering to battle stations. In contrast to DD 022, the Americans noted that this Soviet destroyer had secured all of her hatches and ports (indicating a higher degree of watertight integrity) and that she had her lifeboat rigged and griped down.

The Soviet “Kotlin”-class destroyer BESSLEDNYI (pennant number 022, at left), seen from the deck of the American destroyer USS WALKER (DD-517), was photographed by a U.S. Navy cameraman a short time before the two ships collided in the Sea of Japan during the morning of 10 May 1967. (NHHC Photo # K-36401)

Within two hours after the Walker completed her initial reports, Rear Admiral Harty released another flash message for transmission to the Joint Chiefs. Chargé d’Affaires Cheryakov was summoned from the Soviet Embassy to the State Department to relay a message to his government urging that it should “take prompt steps to halt such harassment.” Elsewhere in Washington, House Republican Leader Gerald R. Ford asserted that Soviet leaders were “seeking to challenge the United States.” He further stated that “we certainly can’t tolerate other such incidents.” The future President suggested that American skippers should be given specific guidance to protect their ships, including utilizing their weapons. The White House press secretary stated that President Johnson “deeply regrets the incidents” and “considers them a matter of concern.”

Meanwhile, Radio Moscow blamed the United States for the collisions. Two days later, the Soviets summoned Ambassador Thompson to deliver a formal protest, claiming that the acts of the United States warships were of “a premeditated, arrogant nature.” A few days later, Admiral Gorshkov, in an article in Izvestiya, accused McClaren of acting with “malicious intent,” and ridiculed the warmonger Gerald Ford for his “irresponsible statement.” The Soviet Navy Commander concluded: “It is not hard to imagine what might happen if warships were to begin shooting at each other when they collide.”

The Soviets subsequently ignored American calls for “Safety at sea talks” until November 1970. On November 9, the British aircraft Ark Royal, operating is waters in the Eastern Mediterranean not too distant from the most recent US-Russian ship encounter, had a Soviet Kotlin-class destroyer Bravvy pass ahead in a deliberate attempt to disrupt flight operations. Apparently, the British did not detail a destroyer to fend off the pesky Soviet DD. Despite the best efforts of Ark Royal’s captain, Ray Lygo, the carrier hit and rolled the Soviet warship, knocking seven sailors overboard. Five of the sailors were recovered but the incident proved fatal for two of Brazzy’s crew.

The next day in Moscow, the Soviets suddenly responded to the Americans long-standing request for safety at sea talks. The Incidents at Sea Agreement was subsequently signed in 1972 with the provision for an annual review to discuss the accord’s implementation and behaviors of the respective forces afloat and above. At the most recent review held in Moscow earlier this month, the over flights of the USS Donald Cook (DD 75) last April in the Baltic by Russian Sukhoi Su-24 aircraft likely made the agenda. Little doubt this latest Gravely-Yaroslav Mudryincident and Mudry’s approach on Dwight D. Eisenhower approach on the Dwight will be reconstructed and studied at next year’s gathering.

NOTE: Sea of Japan excerpt from author’s Preventing Incidents at Sea: The History of the INCSEA Concept, Dalhouse University, Halifax, Nova Scotia (2008).

Mervin K. Linnemeyer

Bill Streifer

Mervin K. Linnemeyer

Mervin K. Linnemeyer

Bill Streifer

Mervin K. Linnemeyer

mk "Duke" Linnemeyer

mk "Duke" Linnemeyer

Mervin K Linnemeyer

Bill Streifer

Bill Streifer

D Ben

Mervin Linnemeyer

Mervin Linnemeyer

Mervin “Duke” Linnemeyer

Harry Gardikis

D Ben