By George Stewart

(This is the second of a series of blog posts that discuss the role that Casco Bay played during the Second World War. This is Part I of the series. “Going Ashore” are the collected posts from George Stewart, retired Navy Captain and NHF blog volunteer. Read the first post HERE).

By 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic was in full swing. Facilities in Casco Bay were fully functional with the exception of a seaplane base and Navy Fuel Annex on Long Island, both of which were still under construction. As previously mentioned, the major functions of the naval base were to provide for shakedown, refresher, and specialized ASW training for DESLANT ships. Battleships and cruisers also used the facilities for training purposes. At least one destroyer tender would always be available to provide repairs and upkeep for ships as required. The base also acted as a staging area for ships assigned to convoy escort and anti-submarine patrols in the North Atlantic and along the Eastern Seaboard. The Eastern Sea Frontier Commander’s responsibilities ranged from the Canadian Border down to Jacksonville, Florida, and out to 200 miles offshore. He was based at 90 Church Street in New York.

Shakedown training occurs shortly after a ship has been commissioned. In those days, it was usually only about seven to ten days in length. This was when the ships crew would get to exercise all of the major ship functions for the first time. Training usually consisted of live firing of the ship’s guns and other weapons systems, damage control and engineering casualty control drills, anchoring and mooring to a buoy, unassisted docking and undocking, underway refueling, towing and being towed, and a variety of other exercises under the watchful eye of the Fleet Training Group instructors. It was a very intense period. During the war, it would have been doubly so, because of the limited time available and the urgent requirement for ships on line. Refresher training was of a similar scope. It was conducted after a ship underwent a major shipyard period. During the war, shakedown and refresher training on the East Coast built ships were conducted either at Casco Bay, Naval Operating Base Bermuda, or at Guantanamo Bay. After the war, all of these functions were handled at “GTMO” for Atlantic Fleet ships.

Destroyers, Destroyer Escort types, and other vessels with anti-submarine capability also underwent specialized ASW training. Much of this training occurred at Casco Bay where training submarines could be readily provided from New London. Conditions were similar to what they would encounter in the North Atlantic. These submarines were normally older types dating back to the First World War, although captured Italian submarines became available to perform this function later on in the war.

The database contains records of 149 vessels that visited Casco Bay in 1942. These included the new battleships USS Washington (BB 56), USS South Dakota (BB 57), USS Indiana (BB 58), and USS Massachusetts (BB 59), plus older battleships like the USS Arkansas (BB 33) and USS Texas (BB 35). The aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV 7) came just prior to its transfer to the Pacific. The eighty-two destroyers on the list were by far the largest group of ships on the list. It appears that at least fifty-nine of them were there for shakedown. Most of these were Benson, Gleaves, and Fletcher types built during the early stages of the war in East Coast shipyards. The twenty-one Fletchers were considered to be the “top of the line” destroyer types at the time. Nearly every ship of this class that trained in Casco Bay during the war was immediately slated for duty in the Pacific, where they were most needed.

Overall, 1942 was a very poor year for the U.S. Navy in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Germans referred to it as their “happy time.” That was all about to change in 1943.

That year started out badly for the navy in the Atlantic with the U-Boat offensive reaching its peak in March 1943. However things would get better in April. The period between April and November 1943 is considered to be the time that the German U-Boat offensive was defeated and the Battle of the Atlantic won. After that, the German Navy was never able to mount an effective submarine offense out of their home waters. The major reason for this turnabout was improved coordination between the various groups that had responsibility for the anti submarine effort.

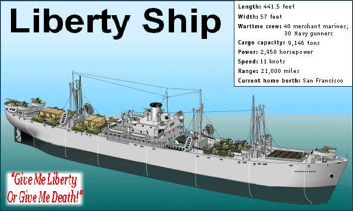

A vital factor in this turn of events was the success of the hunter-killer groups, led by the escort carriers (CVE). A number of these carriers were converted from merchant ship hulls. The year 1943 also saw the introduction of a new type of ship, the Destroyer Escort (DE). These ships only had a maximum speed of 20 to 24 knots. This was adequate for ASW purposes, as the Destroyer Escorts had a tighter turning radius than their destroyer counterparts. It was not until the fall of 1943 that Destroyer Escorts would appear in anything resembling a desired quantity. This freed up Atlantic Fleet destroyers to support the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, and Italy or for service in the Pacific where they were more urgently required. Many DDs and DEs that called at Casco Bay during 1943 served as members of hunter-killer groups or supported the aforementioned invasions.

The Battle of the Atlantic by the numbers:

- 1939 (4 months) – 810 Allied Ships Sunk, 9 U-Boats lost

- 1940 – 4407 Allied Ships Sunk, 22 U-Boats lost

- 1941 – 4398 Allied Ships Sunk, 35 U-Boats lost

- 1942 – 8245 Allied Ships Sunk, 85 U-Boats lost

- 1943 -3611 Allied Ships Sunk, 237 U-Boats lost

The Germans were unable to sustain this rate of losses. The World War II U-Boat had a number of operational limitations. One of the major ones was its limitations with endurance caused by the necessity to surface in order to recharge batteries and maximum underwater speeds of approximately 6 knots. The U-Boats could maintain a speed of about 17 knots on the surface. This speed allowed them to outrun inshore escorts such as World War I built Eagle Boats and converted yachts. But speed on the surface proved little use against aircraft.

As the effectiveness of shore-based patrol aircraft improved, it became possible to provide good coverage, particularly during daylight hours. The ability of aircraft to detect submerged submarines was very limited. Some improvements were made by the invention of the Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD) gear. The invention of radar also greatly improved the ability to detect a surfaced submarine at night.

A major limitation of shore-based aircraft was their relatively limited range. Therefore, there were large gaps in mid ocean where aircraft coverage was unavailable. Much of the reason for the 1943 turnaround during the Battle of the Atlantic was the effectiveness of the hunter-killer groups built around the CVEs and their escorts, which were able to fill most of these gaps.

A ship-aircraft team remains the most effective way to detect and kill submarines. Ships offer detection capability and are able to remain on station for long periods of time, while aircraft offer rapid response, and the ability to easily outrun the submarines and deliver weapons. Modern practice is for destroyers and frigates to carry specialized ASW helicopters referred to as LAMPS (Light airborne multi-purpose systems).

A big advantage of both the CVE and DE types was that both were easily produced and were relatively cheap compared to the full size carriers and destroyers.

A total of 191 ships in the database are shown as visiting Casco Bay in 1943. These included the battleships USS New York (BB 34), USS Texas (BB 35), USS South Dakota (BB 57), USS Massachusetts (BB59), USS Alabama (BB 60), USS Iowa (BB 61), and USS New Jersey (BB 62), and the aircraft carrier USS Ranger (CV 4). There were 104 destroyers on the list, forty of which were Fletcher class ships bound for the Pacific after shakedown. This was the first time that the new Destroyer Escorts appeared on the list with twenty-two visits on record during 1943. Most of these ships were destined for hunter-killer groups in the Atlantic or convoy escort duties in the North Atlantic or Mediterranean.

————————————–

George W. Stewart is a retired US Navy Captain. He is a 1956 graduate of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. During his 30 year naval career, he held two ship commands and served a total of 8 years on naval material inspection boards, during which he conducted trials and inspections aboard over 200 naval vessels. Since his retirement from active naval service in 1986 he has been employed in the ship design industry where he has specialized in the development of concept designs of propulsion and powering systems, some of which have entered active service. He currently holds the title of Chief Marine Engineer at Marine Design Dynamics.

Pingback: Going Ashore: Naval Operations in Casco Bay During World War II | Naval Historical Foundation

Pingback: Going Ashore: Naval Operations in Casco Bay During World War II (Part IV) | Naval Historical Foundation

Zinas M. Mavodones

Randy Finfrock

Tony Flores

robert dyke

Dennis Grim