“This has been an important and great day and on which the Second grand landing of the Americans in Japan took place. I was fortunate enough on the occasion of the First landing to be one of those who landed.” (8 March 1854)

David Dixon Porter. David Glasgow Farragut. Ernest King. William Halsey. These names are well known in the annals of American naval history. Like their contemporaries also included in the Naval Historical Foundation manuscript collection at the Library of Congress, their careers are often bookended by the wars and conflicts we continue to study today. These manuscripts, albeit important, do not give a complete picture of the history of the United States Navy. Holes exist in this supposed narrative. Other files in the manuscript collection tell a different story of the U.S. Navy’s myriad peacetime exploits. These collections are what former Library of Congress Manuscript Historian John McDonough called both “prominent and obscure.”

One of the more intriguing of these “obscure” aspects of 19th century naval history is the 1852-1854 Japan Expedition, led by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry. Although well known for his exploits during the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War, Perry’s greatest contribution to naval history is his mid-century expedition to open Japan.

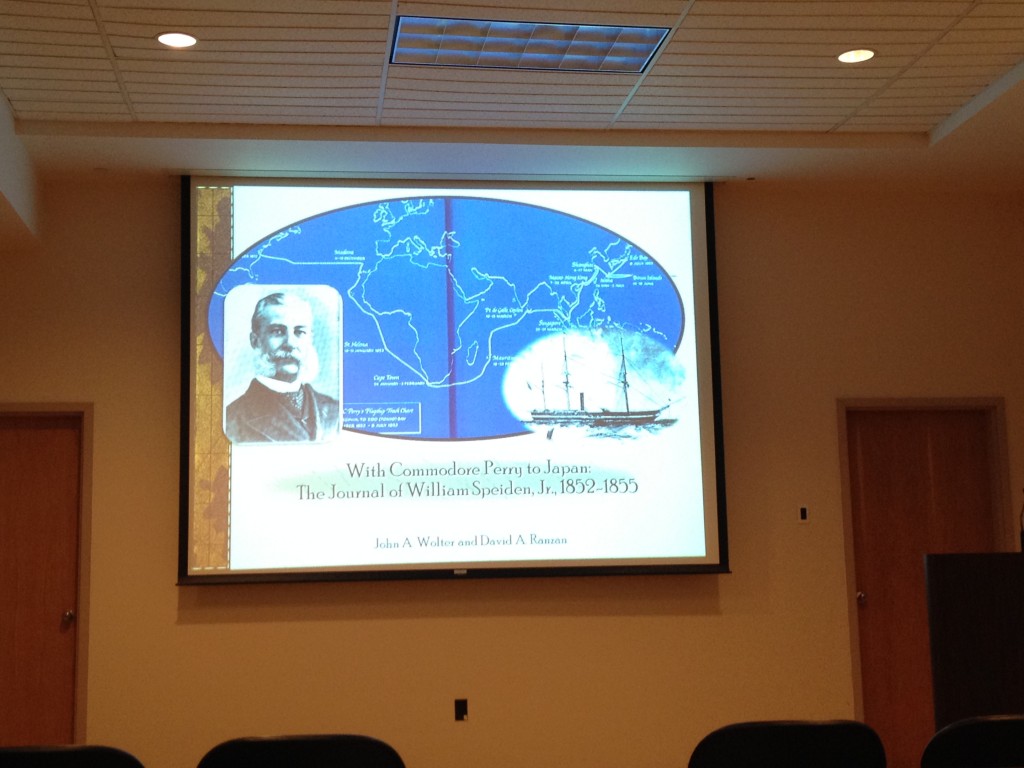

Only a handful of sources faithfully documenting Commodore Perry’s expedition exist today. Fewer are written from the perspective of the crew, not the officers in charge. Thankfully, one recently published source formerly in the NHF collection gives ample information on the expedition. The two volumes comprising USS Mississippi Purser’s Clerk William Speiden, Jr.’s meticulous journals are now available in With Commodore Perry to Japan: The Journal of William Speiden Jr., 1852-1855. Book editor David A. Ranzan stopped by the National Museum of the United States Navy Wednesday to talk about the book and the exploits of an ambitious young man with his eyes open to a new world.

Ranzan spoke briefly about Speiden’s life and his “youthful perspective of the expedition” covered throughout With Commodore Perry to Japan. By all accounts, Ranzan’s description was perfect. Speiden, a Washington, DC native, accepted an appointment as a sixteen-year old purser’s clerk aboard the USS Mississippi alongside is father in 1852. From there, he traveled to far and exotic places, often doing what teenagers his age do best. Whether it was sneaking into the gravesite of Napoleon with his shipmates at St. Helena or setting off firecrackers “like a set of demons” in the streets of Canton, China, Speiden found ample opportunity for amusement while traveling on the squadron’s flagship.

During the squadron’s exploits to Japan in 1853 and 1854, Speiden took a back seat. He was nonetheless there, documenting everything in rich detail:

Friday, March 3: This evening some Japanese officers came on board, this is the first occasion any of them have been on board. They have been exceedingly anxious to see the ship on account of her formidable appearance [. . .] They were friendly and sociable, and before leaving, two of them, the Imperial Interpreter and Lieutenant Governor of Uraga were quite merry.”

Other exciting accounts in Japan include the squadron’s first sighting of the Japanese in Yedo Bay. The nearby Japanese ships attempted to board the American vessels, which were soon repelled. “They must certainly have all come to the opinion that we were a queer sort of people,” Speiden mused in his journal of the event. According to John McDonough, Speiden was “enthusiastic and alert, and made the most of his situation and the opportunities it presented.” The approximately 300-page journal is revised and condensed for interested readers to thumb through. As one may guess when reading, the journal does not appear to be written by a carefree young man diverted by adventures. McDonough explains:

“The journal has a polished and finished appearance, suggesting that Speiden prepared it at a later date or during leisure hours and based it on a rougher version recorded closer to the actual time of the events described.” (Library of Congress Acquisitions: Manuscript Division, 1994-1995)

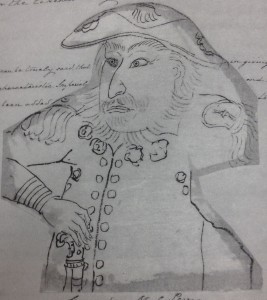

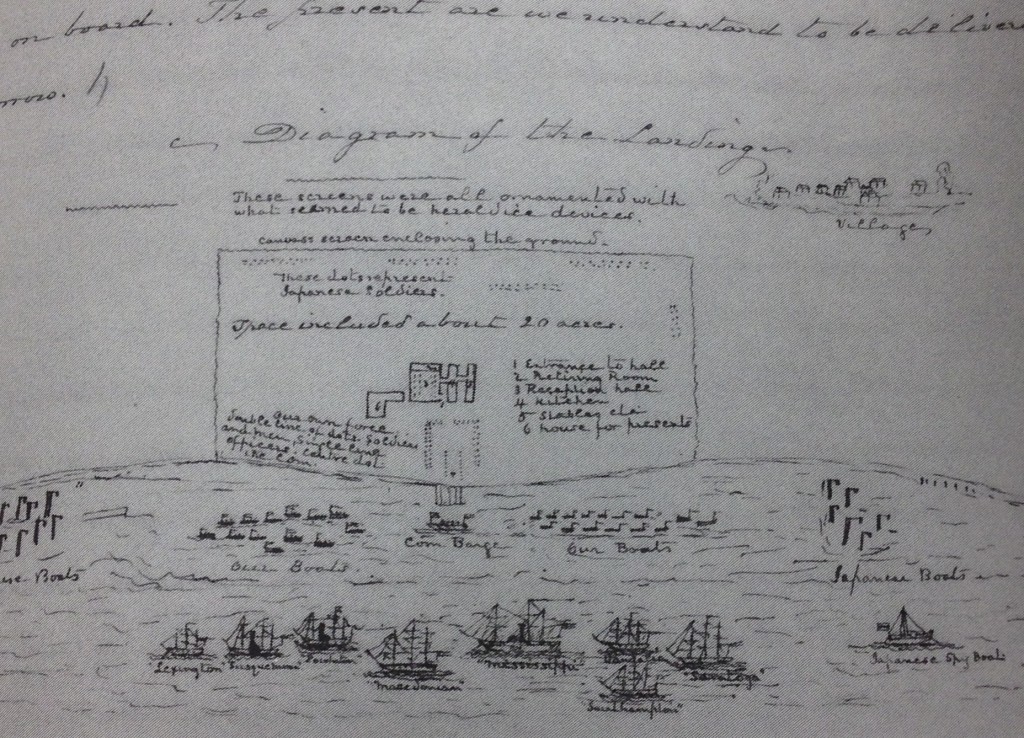

The most impressive aspect of Speiden’s journal are not the words themselves. Rather, Ranzan noted that the journal included nearly fifty “eloquent drawings and illustrations” done by Speiden throughout the voyage. “He was a very gifted artist,” said Ranzan during his lecture. The most impressive sketch is a diagrammatic of the Yokohama landings where the Treaty of Kanagawa negotiations took place, ending the 200-year old Japanese policy of Sakoku (seclusion). Speiden sketched the impressive and informative picture almost two years to the day from the start of his voyage at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

The final words in his journal are a somber ode to two dogs that died while at sea. The dogs were apparently gifts from the Japanese to Perry. His simple and beautiful poem is an introspective end to a historic cruise to the far edges of the map.“Happy dogs to die

Upon the broad blue sea,

For there your bones will lie,

Buried, and forever be.”

David Griffin Stone

Admin